2.3. Language development and identification of dyslexia

Module 2 and the Routemap highlighted the importance of language development. There may be a number of reasons why a learner’s language is not at the expected level for their age.

Activity 7

In your Reflective Log consider some possibilities why this may be the case.

Click ‘reveal’ to see some examples of what we thought.

Discussion

- Speech and Language difficulties

- Speech and Language delay

- EAL

- ASD

- Attention deficit disorder

- Poor/low level spoken vocabulary in the home

- Lack of reciprocal interaction at young developmental age

- Neglect

- Lack of attunement

- Negative inter-generational patterns

- Hearing difficulties

- Parents with poor literacy skills

- Lack of literacy rich experiences in early years

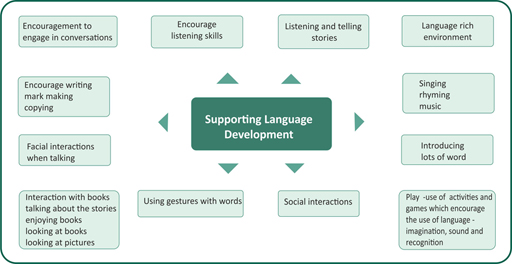

To identify strengths and areas of difficulty of a learner’s language skills it is vital to understand what the term ‘language development’ means. Modules 1 and 2 highlighted areas of literacy development and this contributes to the wider language development as figure 5 highlights.

2.2. Positive aspects of dyslexia