5.1.1 Female genital mutilation (FGM)

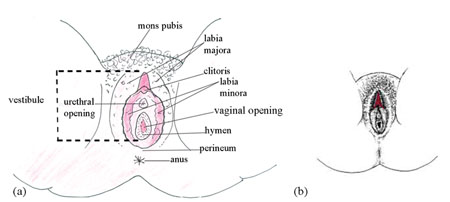

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines female genital mutilation (also called ‘female genital cutting’ or ‘female circumcision’) as any procedure which involves the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia (see Figure 5.1) or which causes any other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or any other non-therapeutic reasons. Instruments used include knives, scissors, razors, and pieces of glass. Occasionally sharp stones and cauterisation (burning) are used.

FGM has no known benefits; instead, it can have both short- and long-term bad consequences for health.

Thinking about the instruments that are used, suggest one short-term bad physical consequence of FGM.

An immediate physical effect of FGM might be bleeding and injury to nearby genital tissue. Since FGM is usually conducted under unhygienic circumstances, it may also result in tetanus or sepsis (bacterial infection) developing very soon.

In the long term, FGM can cause repeated recurrent urinary tract infections, increased risk of childbirth complications and newborn deaths and the need for later surgery. For example, the FGM procedure that seals or narrows a vaginal opening needs to be cut open later in life to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth. Sometimes it is stitched again several times, e.g. after childbirth, hence the woman goes through repeated opening and closing procedures.

There are often psychosocial consequences of FGM (see Box 5.1).

Box 5.1 Consequences of FGM

Short-term physical consequences

- Severe pain (see Case Study 5.1)

- Injury to the adjacent tissue of urethra, vagina, perineum and rectum

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Failure to heal.

Long-term physical consequences

- Difficulty in passing urine

- Recurrent urinary tract infection

- Difficulties in menstrual flow

- Fistula.

Psychosocial consequences

- Mutilation is an occasion marked by fear, and the suppression of feelings. More often the bad memory never leaves the victims.

- Some women report that they suffer pain during sexual intercourse and menstruation.

- The experience is associated with sleeplessness, nightmares, loss of appetite, weight loss or excessive weight gain.

- As they grow older, women may develop feelings of incompleteness, loss of self-esteem/confidence, and depression/sadness.

Now read Case Study 5.1.

Case Study 5.1 Almaz

Almaz is a seven-year-old living in Southern Ethiopia. Her parents have decided that she will be ‘circumcised’ because they believe that without it, she won’t be married (Figure 5.2). They believe it is a kind of ‘cleaning’. No one has explained to Almaz exactly what will happen to her on the day of her circumcision. Abebech, a 65-year-old known traditional practitioner, used a new razorblade to cut her genitalia. The practitioner needed six women to hold Almaz down.

Almaz almost lost consciousness because of the pain, and shortly after the procedure she was taken to her parents as she was not able to walk on her own.

Stop reading for a moment. Have you yourself experienced FGM or do you know someone in your village who has undergone the same procedure? If so, what are the reasons for it? What is the usual age at which girls undergo FGM in your community? What roles can you play to stop the practice?

Although FGM is recognised as a violation of human rights under Ethiopian law, it continues to be practised in many regions of Ethiopia. A study in 2005 indicated that three in four Ethiopian women aged 15–49 had undergone some form of FGM.

The age at which girls are made to undergo FGM varies from region to region. In Amhara and Tigray, for example, FGM is performed at infancy, usually on the eighth day after birth. In Somalia, Afar and Oromia, girls are subjected to FGM between the ages of seven and nine, or just before marriage between the ages of 15 and 17. According to the same study (in 2005), FGM is highest in Afar, where 85% of women have a daughter with genital mutilation, and lowest in Gambela, where 11% of women have a daughter with mutilation. It is a shocking measure of deep-rooted gender inequality that one in three rural women believes that the practice should continue.

There are a variety of reasons why FGM continues to be practised. You have already reflected on the reasons that are given for FGM in your community. Box 5.2 gives reasons that are commonly reported.

Box 5.2 Reasons given by communities for practising FGM

- Sociocultural reasons: in some communities, FGM is believed to ensure a girl’s virginity and thereby her family’s honour, because virginity is often a prerequisite for marriage.

- Psychosexual reasons: in some communities the unexcised girl is believed to have an overactive and uncontrollable sex drive which makes her likely to lose her virginity prematurely, disgracing her family and damaging her chances of marriage.

- Spiritual and religious reasons: for some communities, removing the external genitalia is necessary to make a girl spiritually clean and is therefore required by religion. Muslims who practise FGM tend to believe that it is required by the Koran. However, FGM is not mentioned in the Koran.

- Hygienic and aesthetic reasons: in some cultures, woman’s external genitalia are considered as ugly and dirty and removing these parts of the external genitalia is believed to make girls hygienically clean.

It is important to note that all the above reasons for practicing FGM are based on false beliefs that FGM has advantages for the girls and their community. You will learn and teach others that none of these reasons are true. In fact, FGM harms women’s sexual and reproductive health. In particular it can cause difficulties during childbirth.

As a health worker, you need to acknowledge the fact that it is not easy to change such a tradition when it has been believed by many generations of people in your community. That is why it needs constant teaching and society’s support to stop the practice. It is especially helpful if men can accept that it is damaging to their daughters and if the women who perform the procedure can be convinced that it needs to stop. (Remember that this will be very hard for them as they would lose a source of income).

5.1 Harmful traditional practices (HTPs)