In media output across much of the world, accompanied by countless discussions on online forums and across various websites, there has been a considerable amount of commentary following the publication of the latest Oxfam report on the extent of global inequality.

In media output across much of the world, accompanied by countless discussions on online forums and across various websites, there has been a considerable amount of commentary following the publication of the latest Oxfam report on the extent of global inequality.

The new 2016 report, An Economy for the 1%, was published to coincide with the latest World Economic Forum event in Davos, Switzerland. The report highlights that we live in a world of growing inequality: a deepening and widening gulf between the richest 1% and the rest of humanity.

Oxfam calculate that the 62 richest people in the world have since 2010 seen their wealth increase by 44%, equivalent to more than half a trillion dollars. Yes you read that right, half a trillion. By contrast the bottom half of the global population, a mere 3.5 billion people, saw their share of global wealth drop by an astonishing $1 trillion dollars, which is 41%. Over the same period the world’s population has grown by some 400m people....the 62 richest people in the world have since 2010 seen their wealth increase by 44%

Such a divide between the richest handful of people and the rest of the population greatly exceeds the available figures for the past century and more. The latest figures are literally off the scale. Depicting the rising wealth of the global financial elite is becoming a harder and harder task and, as is well known, the data provided by Oxfam deals only with recorded wealth, with much of the wealth of the super-rich hidden away in assorted hide-a-ways around the world, the names of many of which are increasingly as familiar to us as are overseas holiday destinations.

Visualising inequality

This aside, it is a difficult task to even begin to grasp the enormity of these inequalities and the myriad of social harms and social problems that they generate, never mind to present them in a way that is meaningful. And this is where assorted modes of transport can come in handy!

Oxfam and The Guardian have used images of vastly expensive super yachts as a way of depicting wealth and affluence, yachts often regarded as the ultimate status symbol that reflects someone’s wealth and privilege.

That much of global wealth is hidden, and the way in which the powers, privileges and massive advantages it generates for the wealthy are obscured, means that it is often difficult to imagine and understand the enormity of what is being talked about here. The yacht in the Oxfam image above might comfortably hold the world’s richest 85 people, though horror of horrors, they may not all have their own gold plated en-suite bathroom and may even have to share! The vast majority of us tend not to see or use such yachts so it is again difficult to really grasp what this signifies.

What about another form of transport, a jet aeroplane? Well more and more people have experience of using this form of transport, even if it remains a minority of the world’s population. They too can be used to depict personal wealth and affluence but once again, the privileges such ownership reflects and generates are difficult to comprehend. 62 people would fit easily into some smaller privately owned planes and can fly around the world on a whim but for the vast majority of us that depicts a world far removed from the vast majority of people across the planet.

Might another form of transport help us grasp the sheer scale of the inequality that has emerged? Take a double-decker bus. It would normally hold around 70-80 people. Single decker coaches can have a capacity of around 50-65. So to take Oxfam’s latest figures, the world’s 62 richest people could have a comfortable day out on one of these buses. In other words, one single bus load of people have as much wealth as the 3.5 billion people that comprise the bottom half of the global population.

Concentration of wealth

There is something else going on here: wealth is being concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. The number of people whose wealth is equal to the poorest half of the world’s population is comprising fewer and fewer individuals. We might only need a mini bus to hold them in the near future… then maybe just a Mini.

| Year | Number of people |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 308 |

| 2011 | 177 |

| 2012 | 159 |

| 2013 | 92 |

| 2014 | 80 |

| 2015 | 62 |

Another way to look at this is to consider the increasing concentration of wealth in fewer and fewer hands in the UK:

| Year | Collective wealth |

|---|---|

| 1997 | £98 billion |

| 2008 | £413 billion |

| 2010 | £336 billion |

| 2012 | £414 billion |

| 2013 | £450 billion |

| 2014 | £519 billion |

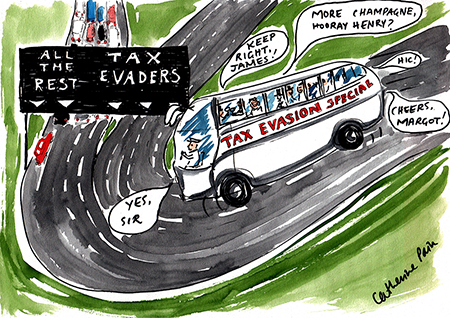

Important as it is, depicting wealth is one thing, but explaining it and making sense of why there is such growing inequality on a global scale is another. For Oxfam a key factor is tax evasion. Oxfam estimates that $7.6 trillion of individuals’ wealth sits offshore, thereby avoiding tax of around $190b per annum. That is tax lost to governments and which could pay for better education, improved healthcare and go far in addressing some of the worst aspects of poverty. Ensuring that large corporate bodies, many of which will be represented at the Davos summit, pay their taxes is central to Oxfam’s arguments about how to address such rising inequalities.

Social harms and austerity

$7.6 trillion of individuals’ wealth sits offshore, thereby avoiding tax of around $190b per annum

The Oxfam report is in some respects the latest in a growing volume of books, studies, reports, filmed, audio and web-based documentaries which in recent years have drawn attention to the ways such inequalities affect us all. The social harms created by economic inequalities reach almost every part of our world today, and affect daily life in so many different ways, many of which we may never have considered.

It is important to understand that the increasing social harms caused by rising inequalities are occurring at the same time as unprecedented attacks by different governments across the world on the incomes of the most disadvantaged. The UK government, for example, is drastically reducing public spending, cutting welfare benefits and eroding hard won conditions of employment across large swathes of the public sector. At the same time, in 2013-2014 alone, the wealth of the richest 1% in the UK increased by 15%, around £519b. Again this is hard to imagine and appears as somewhat abstract; what do these figures really mean? If we looked at UK public spending then we can begin to grasp the enormity of these sums: £519 billion would fund the entire UK education system for almost 6 years, or the state pension bill for 4 years, or the NHS for just over 4 years. It’s almost 5 times the size of the country’s annual welfare bill – which is currently the target of UK government spending reductions, all in the guise of ‘austerity’.

There is no inevitability about the figures provided by Oxfam and many others that point to an increasingly divided and unequal world. This has come about not by accident or by some mysterious natural process over which we have no control. ‘Austerity’ is part and parcel of a wider strategy of inequality that is leading to the vast gulf in wealth that has been depicted here. Across the UK and elsewhere in Europe, austerity programmes have or are dismantling not only benefits and services, but also the mechanisms and structures which work to reduce inequality and enhance equity.

Cutting wages, in work and out of work benefits, pensions and so on is also about restoring conditions for profit and wealth accumulation. This amounts to little more than the transfer of wealth and power into ever fewer hands – the consolidation and advancement of the economic and political interests of the already rich and affluent. ‘Austerity’ is a political project rooted in the defence and consolidation of particular class interests. It represents little more than a political assault on the foundations of the post-1945 welfare state and the idea enshrined in the post-1945 social contract that the state has a vital role to play in reducing inequalities by providing benefits and services.

Courting the super rich

Instead today, across the world national state governments and transnational institutions are active in pursuing the interests of the global rich. The meeting at Davos represents little more than the coming together of those representing the global rich, the large corporations and so on. While the super-rich enjoy a life of expensive private yachts, private jets and expensive vehicles, the poorest and disadvantaged populations of the world are increasingly blamed for their own predicament, stigmatised as among the major causes of global social problems. While ‘austerity’ promotes the ‘sucking upwards' of income and wealth to the already rich, never mind any so-called ‘trickle down’, the most disadvantaged and marginalised are represented as dysfunctional trouble makers.

However, it is very much the case that our societies today do have a dysfunctional minority that generates social harms: the super-rich, whose daily life is both a world apart from that of the overwhelming majority of the global population and yet is so dependent on the exploitation, marginalisation and oppression of that same population. Are we really, to deploy a favourite phrase of David Cameron, ‘all in this together’?

This blog post is part of Society Matters. The blog seeks to inform, stimulate and challenge our understanding of this changing world and of our humbling role within it.

Want to know more about studying social sciences at The Open University? Visit the Social Sciences faculty site.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Society Matters posts are those of the individual authors, and do not represent the views of The Open University.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews