Find out more about The Open University's History and Social Sciences courses.

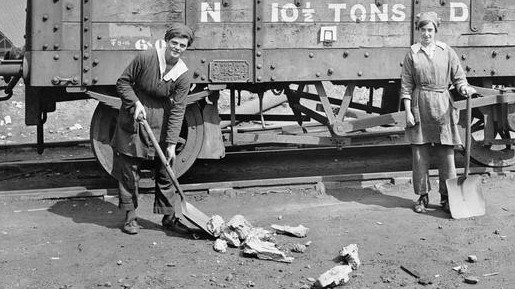

With the introduction of conscription in 1916 leading to over 100,000 men in Scotland leaving to fight in the First World War, women had to step in to fill the jobs that men had left. Many of these jobs were on the railway and it had never been imagined that women would be able to do this type of work previously. Society was very different and, if women did work, it would generally be in service and, even then, they would be expected to leave when they married. Attitudes were very different towards women; many jobs would be considered improper, or it was thought that ‘the fairer sex’ would be incapable of carrying out this work.

Women working as ticket collectors during the First World WarThe Railway Sheet and

official Gazette stated that: ‘The first aim of a woman’s existence is

marriage, that accomplished, the next is ordering her home.’ Yet women were

keen to step in and step into these roles. They proved very capable, but they

had the additional challenges of their clothing. Before the war women’s

clothing was dictated by very strict societal dress codes and it would never be

considered that a woman would wear trousers or be seen out in public without

gloves and a hat. Long skirts and petticoats did not suit the industrial

environment which women found themselves working in. Their clothing proved to

be dangerous and, in some cases, fatal. Gradually it became accepted that women

would need to wear more practical clothing for their new roles. However, no

matter how capable women were at their jobs society still judged them on their

appearance. The newspapers of the day would still place the emphasis on how

well turned out she was.

Women working as ticket collectors during the First World WarThe Railway Sheet and

official Gazette stated that: ‘The first aim of a woman’s existence is

marriage, that accomplished, the next is ordering her home.’ Yet women were

keen to step in and step into these roles. They proved very capable, but they

had the additional challenges of their clothing. Before the war women’s

clothing was dictated by very strict societal dress codes and it would never be

considered that a woman would wear trousers or be seen out in public without

gloves and a hat. Long skirts and petticoats did not suit the industrial

environment which women found themselves working in. Their clothing proved to

be dangerous and, in some cases, fatal. Gradually it became accepted that women

would need to wear more practical clothing for their new roles. However, no

matter how capable women were at their jobs society still judged them on their

appearance. The newspapers of the day would still place the emphasis on how

well turned out she was.

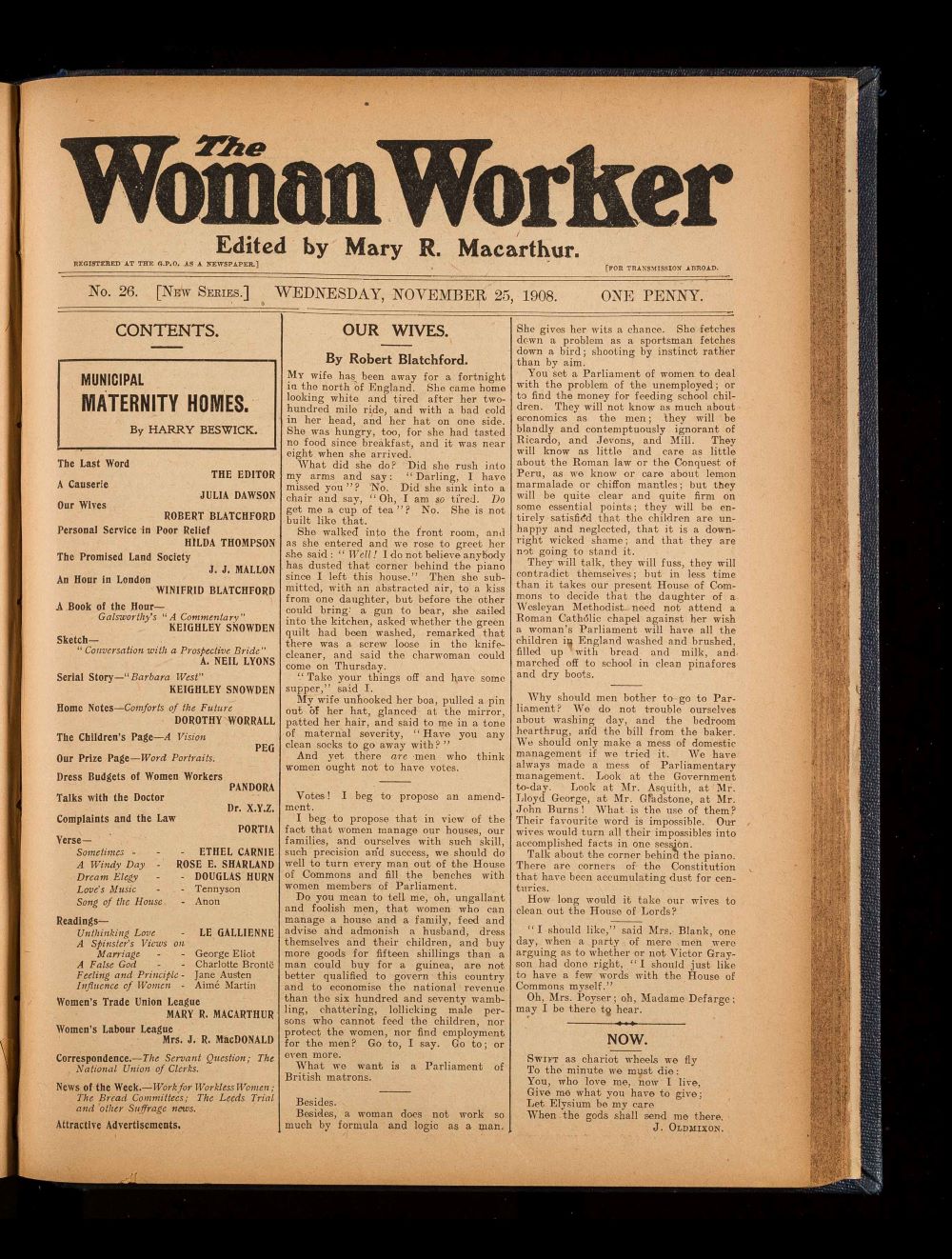

Woman railway worker in the locomotive cleaning pit, 1918.Although women were working on the railway and in other ‘male

roles’ they were still unable to vote. They were however allowed to join the

trade unions and one of the leading trade unionists was Scottish

Suffragist Mary Reid Anderson (nee MacArthur), born in Glasgow in 1880. Mary

was one of the founding members of the National Federation of Women Workers.

She moved down to London in 1903 as secretary and also became editor of the Woman

Worker, a magazine aimed at, in the words of Mary: ‘To teach the need for

unity, to help improve working conditions, to present a monthly picture of the

many activities of many women Trade Unionists, to discuss all questions

affecting the interests and welfare of women. Such in brief, is our aim and

purpose.’

Woman railway worker in the locomotive cleaning pit, 1918.Although women were working on the railway and in other ‘male

roles’ they were still unable to vote. They were however allowed to join the

trade unions and one of the leading trade unionists was Scottish

Suffragist Mary Reid Anderson (nee MacArthur), born in Glasgow in 1880. Mary

was one of the founding members of the National Federation of Women Workers.

She moved down to London in 1903 as secretary and also became editor of the Woman

Worker, a magazine aimed at, in the words of Mary: ‘To teach the need for

unity, to help improve working conditions, to present a monthly picture of the

many activities of many women Trade Unionists, to discuss all questions

affecting the interests and welfare of women. Such in brief, is our aim and

purpose.’

An interesting article in edition 26 (25 November 1908), written by Robert Blatchford, socialist campaigner and journalist about the return of his wife, shows that even though a woman might be working or away campaigning she would still be responsible for running the home and looking after the children. Robert suggests that women should be given the vote and their place in parliament as he feels that although women may not have the knowledge of economics and such, the skills they have for running a household would make them more than capable of running the country. ‘Look at the government today, look at Mr Asquith, at Mr Lloyd George, at Mr Gladstone, at Mr John Burns! What is the use of them? Their favourite word is impossible. Our wives would turn all their Impossibles into accomplished facts in one session.’

Image courtesy of The Digital Library

Image courtesy of The Digital Library

For the women working on the railway, being members of a trade union at the time did not mean equal rights as many of the main unions were resistant to women taking up what had been previously considered male jobs. Women were still paid less, due in part to companies employing two women to do the work of one man in an attempt to keep the roles part time. There was a fear among the men that because the female workforce was cheaper, they would not be able to return to their jobs on return from the war. The unions put strict conditions on women being able to work including: women’s war work not setting a precedent for peace time work, soldiers returning from war would be guaranteed reinstatement and where women were doing the job of a skilled man, they would earn the same as men but only for the duration of the war. In the register of The National Union of Railwaymen, (The Railway: A woman's World) the women’s names were written in red ink so that they could be easily identified and erased at the end of the war. When the war was over the men returned to their jobs, leaving many of the women to either go back into service or to family life. However, in 1918 some women were given the vote and undoubtably women’s lives and their place in society had changed never to be the same again.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews