2 Global literacy and ‘literacy for all’

A global agenda of education for all has long been seen as the means of enabling social, economic and human development. This has been particularly evident in the work of the United Nations (UN), for example, the 1960 Convention Against Discrimination in Education, and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, which enshrined a right to education. In 1990, a World Declaration on Education for All was adopted in Jomtien, Thailand, by participants from 155 countries and representatives of 150 governmental and non-governmental agencies. Global literacy is seen by many to be central to this agenda. For instance, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) views literacy as being at the heart of a ‘basic education for all’ and promotes literacy as being essential for individual self-actualisation, personal growth and social progress. (See, for example, the literacy section of the UNESCO website [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ). However, achieving literacy for all has been and continues to be extremely problematic, with the failure of numerous literacy campaigns over the past decades (see, for example, Elwert, 2001).

Literacy campaigns designed to promote ‘literacy for all’ are only seen to be successful if engagement with literacy is sustained and maintained over a period of time. It is also recognised by many literacy educators that achieving the aim of ‘literacy for all’ requires more than a focus on basic, functional literacy. However, despite this, most global literacy campaigns have focused on functional literacy rather than a wider view of literacy, which encompasses the promotion of personal empowerment and supports wider social and human development.

As seen from the UNESCO statement on literacy, literacy for all stresses the developmental and societal impact of increasing literacy rates. The literacy for all agenda is seen as empowering and giving learners agency. Increasingly, however, it has become evident that the goal of literacy for all cannot be achieved by concentrating solely on an individual’s ability to read and write.

For text-based literacy to become a self-sustaining activity there has to be the development of a literate environment and culture that fosters social interaction and interaction (see, for example, Elwert, 2001; Goody, 1986; Street, 2013). Literacy learners need to find material that is relevant for them to read; they also need to be immersed in a literate environment. This requires print-rich educational settings, which promote written language and text-based communication. A history of literacy campaigns has also shown that for literacy for all to be sustained, and for it to contribute to empowerment and human development, it must seen to have a social as well as an economic purpose. For example, Elwert (2001), in his analysis of the failure of literacy campaigns in promoting literacy for human development, argues that literacy is only sustainable and self-producing if it is tied to both social and economic development.

Activity 2

1. Read Leach, A. (2014) ‘Not just a numbers game: improving global literacy’, Guardian, 17 February.

Answer the following questions:

- a.What was your first impression of the UN brief mentioned in paragraph 1 of this reading?

- b.What were your thoughts about this brief after reading paragraph 2?

- c.What do you think about the reasons behind and critiques of the UN goal of literacy for all given in the last two paragraphs of the article?

- d.What views are you developing on literacy and the goal of making everyone literate?

2. Search for articles and information about global literacy and goals related to achieving literacy for all. To narrow down your search, you may want to focus initially on a couple of newspaper articles and relevant policy documents and use these as a starting point to find more information.

Discussion

The authors of this course searched for newspapers, policy documents and educational development literature related to global agencies such as UNESCO and its predecessors. We found world literacy/illiteracy maps in UNESCO publications particularly interesting.

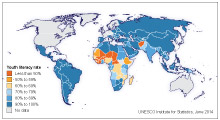

For example, the UNESCO maps (e.g. the June 2014 map reproduced as Figure 1 below) appeared to emphasise the links between the compulsory access to schooling and higher literacy rates. The maps related to adult literacy seem to highlight the connection between economic development and low adult literacy rates.

However, we also noted that, as indicated by Leach (2014), developing literacy for all in an empowering way and for social betterment is not a straightforward, unproblematic process. Global and local literacy development is mediated by a number of different factors such as class, gender, social status, home language and location (rural or urban). These factors impact on literacy rates in various ways in different countries and local areas.

The literature on global and national literacy development suggests that the view of literacy skills as having the potential to develop economic and social progress has long been accepted and has been one of the arguments that has been used to support the development of compulsory schooling in many countries. We can also see an increasing emphasis on the economic cost of poor literacy levels over the past couple of decades. This is often linked to arguments for raising national and global literacy standards.

You may have found that, like Leach (2014), your search through the literature and sources raised questions and highlighted the complexity of achieving literacy for all, which is relevant to those engaged in supporting learners to become literate. For example, can we only focus on teaching functional literacy if we want to empower learners to engage with and be included in all aspects of the world that they live in? If we value participation and social engagement as a key aspect of inclusive practice, should we be supporting literacy for all purely in terms of a supposed economic gain for the wider society?