Google ‘Unprofessional Hairstyles for Women’. Now have a look at ‘Professional Hairstyles for Women’. Notice anything?

In a popular magazine article about the understudied relationship between Black women and their hair, one researcher writes: ‘If cultural theorists want to understand how Black women and girls view their worlds, it is essential to understand why hair matters to them’ (Bank, 2004). For the vast majority of Black women and girls, hair is not just hair; it contains emotive qualities that are linked to one’s lived experience and identification. Historically, hair has held significant roles in traditional African societies, including being a part of some language and communication systems. For instance, during the fifteenth century, African people such as the Wolof, Mende, Mandingo and Yoruba ethnic groups used hairstyles as means to carry messages or as status symbols, such as denoting age, religion, social rank and marital status.

One of the unique features of African textured hair is its ability to be sculpted and moulded into various shapes and forms hence, while hair may play a significant role in the lives of people of all racialised groups, for people of African descent, this role is amplified due to the unique nature and texture of *Black hair. Since antiquity, Black hairstyles have been known for their complexity and multifaceted nature, a notion that continues today.

However, African textured hair in its natural state has and is often negatively marked for its (negative) ‘difference’ to Caucasian hair. Many Black women have wrestled with the concept of ‘good vs bad’ hair as far back as the beginning of the mid-1800s when the European enslavement of African peoples was a system (Randle, 2015). Through European colonisation, Christianity and the enslavement of African peoples, light features like blonde hair, blue eyes and fair skin were believed to be physical manifestations of ‘the light of God’. To justify the enslavement and inhumane exploitation of Black people, enslavers dehumanised them, including referring to their hair as ‘woolly’ or with other animalistic terms (which is why asking to touch a Black person’s hair is so egregious), or simply shaving it all off. This meant that tightly coiled tresses were considered deplorable when pitted against the long, straight European hair that was considered beautiful and attractive. In this way, colonialism gave capitalism a brilliant business model to follow as it illustrated just how easy it is to profit off deep-seated insecurities stemming from a lifetime of being treated as ‘less than’ (see Amin, 1990).

It is worthy of note here that ‘locs’, a natural hairstyle that has historically been worn across several civilisations and cultures, has been and is often referred to as ‘dreadlocks’. There are current debates about the history of this term towards African people in that European colonisers denigrated Kenya warriors with this locs hairstyle as frightening and dreadful – hence ‘dreadlocks’. In contemporary society many associate this locs hairstyle with Rastafarianism and the reggae legend that is Bob Marley. However, along with the selective and sanitised ‘One Love’ of Bob Marley, Usain Bolt and Sandals holiday resorts, this style is subliminally associated with drug-related activities or countercultural movements. Many people understanding this contemporary education piece now refer to this hairstyle as ‘locs’, and professional hairstylists caring for this style (as this style is often considered incorrectly as ‘dirty’ and about not washing hair or allowing it to just become matted) are Locticians.

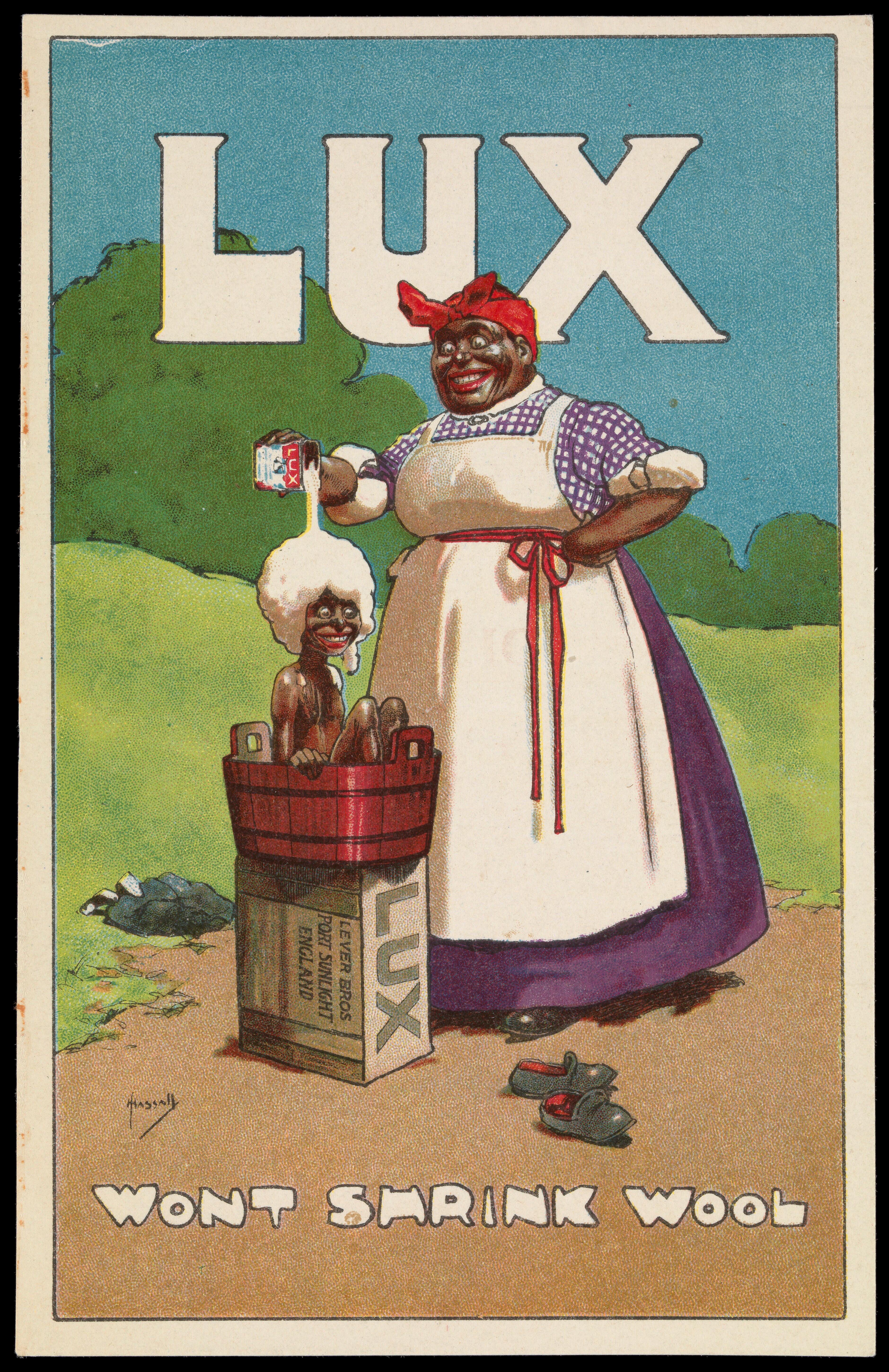

Nineteenth-century US advertisement.

Nineteenth-century US advertisement.

Show me the money

Madame C.J. Walker, the first Black female millionaire, received a patent for developing the ‘hot comb’, also known as the ‘pressing comb’, with the premise that straight hair meant higher social and economic opportunities for Black women. Once the straightened hair was exposed to moisture, however, it would revert to its original condition. In 1906 George. E. Johnson’s chemical sodium chloride straightener, also known as a ‘relaxer’, was promoted as a less damaging hair product and a more permanent style condition. During the late 1800s and 1900 advertisements from White manufacturers targeting a Black audience indicated that their products would add value to African women who ‘lacked’ the beauty and feminine graces of white women. The ads played upon already held notions of hair and race inferiority that were prevalent in white and Black communities (Johnson and Bankhead, 2014).

Over a century later, Byrd and Tharps (2001) provide a detailed survey of Black hair from its historical roots to the business and politicisation of Black hair, and describe the ritualistic nature that ‘straightening’ serves as a rite of passage for most young Black girls from childhood into adolescence and womanhood (Thompson, 2008-9). However, although many today are formaldehyde ‘Ly Free, the latest research on the effects of contemporary hair relaxers, which evidences Black women who have used chemical relaxers more than twice a year for more than five years have an increased risk of developing uterine cancer. Black women who used hair products containing Lye at least seven times a year for more than fifteen years had a thirty per cent increased risk of developing breast cancer. The US Food and Drug Administration is currently planning to propose a ban on formaldehyde and other formaldehyde-releasing chemicals like methylene glycol, which are found in many hair-straightening products. The target date for the proposed ban is set for April 2024.

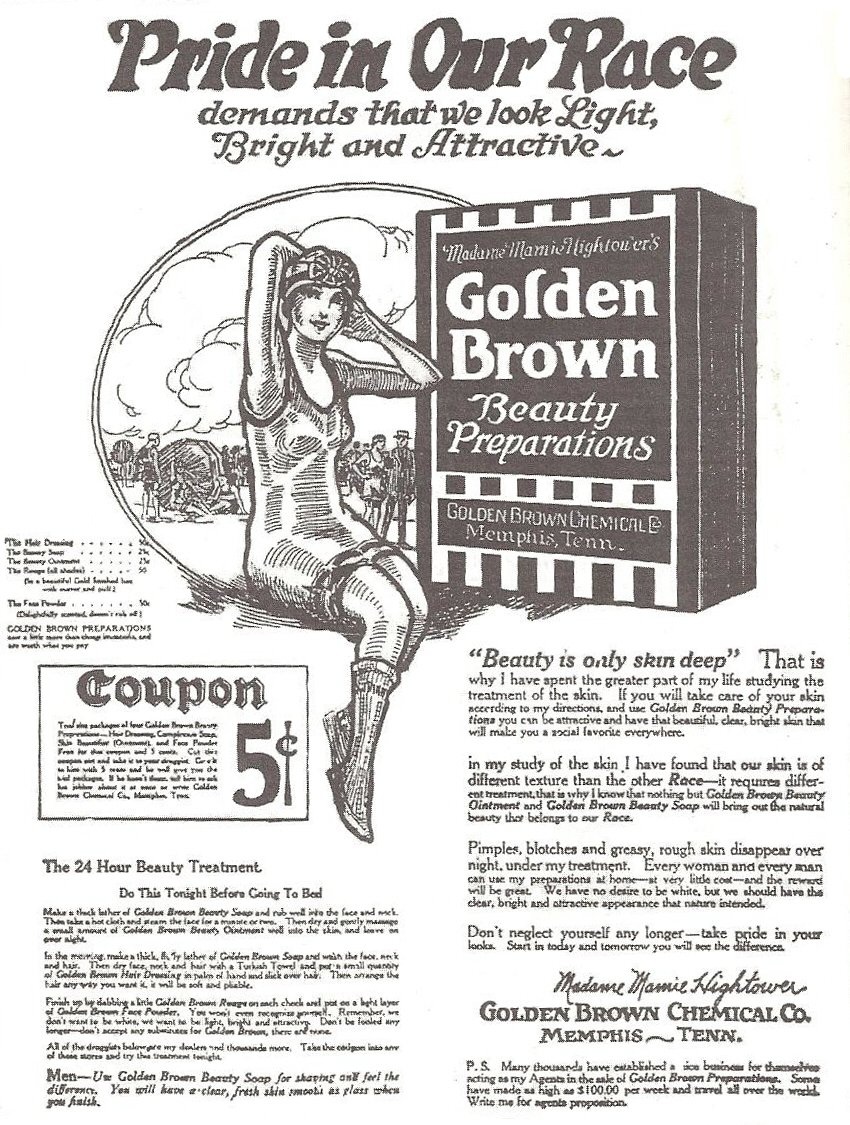

1923 US advertisement for skin bleaching.

1923 US advertisement for skin bleaching.

The Internalisation of White Standards of Beauty

The famous 1940s Clark & Clark ‘Doll Test’ (which has been replicated several times since) evidenced Black children’s internalised racism in their preference for white dolls which they deemed ‘good’ and themselves as ‘bad’. Much academic research on the cultural practice of skin lightening within many Black and Asian communities aligns with Bank’s research where she argues that hair straightening practices are ‘indicative of a hatred of black physical features and an emulation of white physical characteristics’ (Banks, 2000).

Black women’s idealised beauty standards about how to wear their hair have been informed by dominant societal pressures to adopt Eurocentric standards of hairstyles, whether fashionably wavy, curly or straight, but usually long. Beauty is related to the transference of power and ‘good’ hair is perceived as the hair closest to white people’s hair – long, straight, silky, bouncy, manageable, healthy and shiny – while ‘bad’ hair is ‘short, matted, kinky, nappy, coarse, brittle and woolly’ (Johnson and Bankhead, 2014).

Consequently, terms such as ‘good hair’ have become a code for Caucasian straight hair, granting more power and social capital. Indeed, the idealisation of Eurocentric femininity with her long blonde hair and blue eyes was the iconic Barbie doll created in 1959. In 1967 Barbie had a Black friend, ‘Colored Francie’, and ‘Christie’ a year later who were literally made from the same Barbie mould with the same facial Eurocentric features, the only difference being darker skin and dark long hair. It was two decades later in 1980 that a Black Barbie designed by Black creator Louvenia ‘Kitty’ Black Perkins debuted with short curly afro and fuller lips.

Symbolism and Black Hair

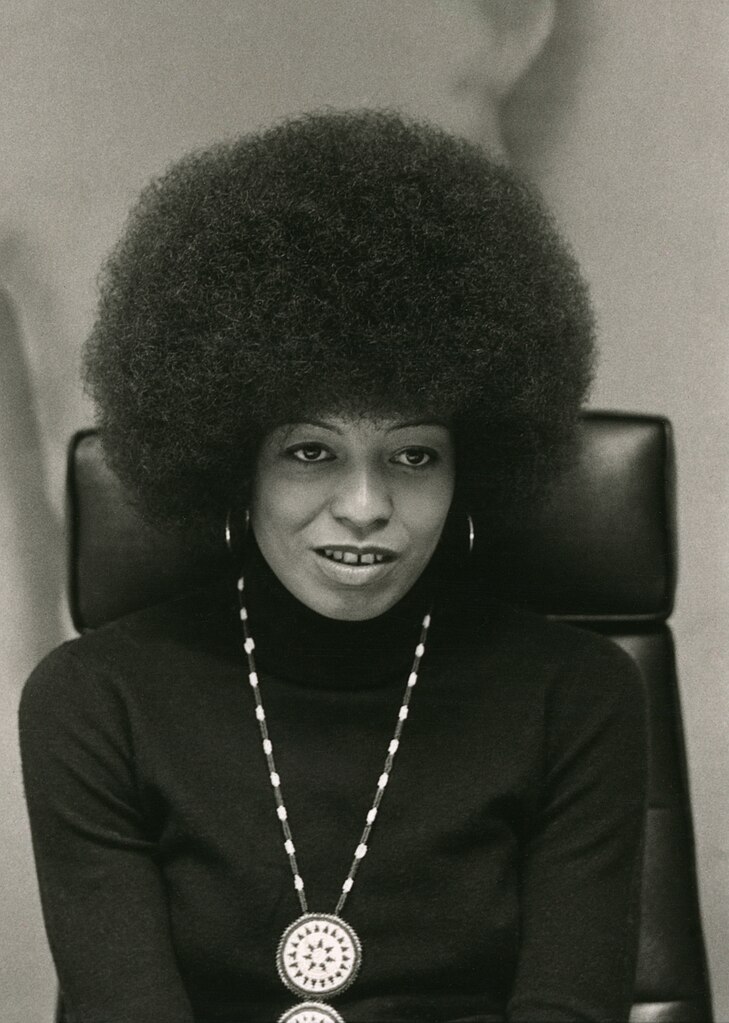

In the United States during the 1960s, Afrocentric hair began to be positively associated with the quest for equal rights in the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. During this time, the slogan ‘Black is Beautiful’ was created to offset negative stereotypes about Black beauty (Hooks, 1995). Yet, by the 1970s, the Afro hairstyle, although Angela Y. Davis became the poster girl of the Black Panther party, had become largely masculinised in part because of its close association with the largely male, militant leadership of the Black Panthers (Kelley, 1997).

Subsequently, there was a negative reaction to Black women wearing Afros with the connotation and lasting stereotype of the political, dominant, aggressive and counterculture Black woman. Kelley surmises this created a dynamic where Black women began to experience pressure to straighten their hair to be a Europeanised ideal of femininity. Thus, since the 1970s, Black women donning Afros and other Afrocentric hairstyles in general, have been viewed as more masculinised than their Eurocentrically coifed counterparts (Opie and Phillips, 2015), although more recently this ‘retro’ hairstyle has been embraced by some younger Black males.

From the 1980s to date, ‘weaves’ raised the Black beauty bar even higher to hair that is not just straight, but also very long (Banks, 2000; Byrd and Tharps, 2001; Tate, 2007). Hair weaving is a process by which synthetic or human hair is sewn into one's own natural hair. There are many different ways to wear a weave. A woman may braid her hair and then sew ‘tracks’ (strips of hair) onto the braided hair or use a bonding method where tracks can be glued to the hair at the root. Braid extensions are similarly a method where synthetic or human hair is braided into a person’s own hair, thereby creating the illusion of long hair with the plus side that they can stay in for a prolonged period of time. Celebrities like Janet Jackson, Diana Ross, Naomi Campbell, Beyonce and Rihanna are some celebrities who frequently wear weaves to suit their music and fashion styling and to rest their own hair. Wig wearing through the centuries has also been a way for Black women for societal conformity, expressions of culture, fashion or to rest their hair.

However, it is worthy of note that many Black female celebrities are usually those with more Caucasian-like features (i.e. straight/long hair, smaller lips, and smaller/straighter noses) as opposed to those with what is commonly thought of as distinct African features (i.e. tightly coiled/kinky hair, full lips, broad noses, etc.). There are ongoing debates about the cultural appropriation of white women braiding their hair and not acknowledging the historical roots of African hair symbolism. For example in 1979 the film entitled ‘10’, starring the white female protagonist, Bo Derek caused a ‘revolutionary’ fashion sensation when she wore braided hair, with many white women clamouring to have ‘Bo Derek Braids’. Currently on Pinterest, Bo Derek’s hairstyle is under the heading ‘The 100 Most Iconic Styles of All Time’. In 2020 when Kim Kardashian, a mother of African American children, credited her wearing of a braided hairstyle to Bo Derek, there was much criticism by Black women of her personal cultural ignorance and the regular ‘whitewashing’ and historicity of African history in the media.

Angela Y. Davis in 1974.

Angela Y. Davis in 1974.

Because I’m Worth It

An example of the Eurocentric standard for hair care, the professional swimming cap, was, among other uses, designed to prevent Caucasian hair from flowing into the face. At the Tokyo Olympics in 2020 a swimming cap called Soul Cap, designed for natural Afro textured hair by a Black owned brand, was rejected for use by the International Swimming Federation as it did not fit ’the natural form of the head’ and to their ‘best knowledge the athletes competing at the international events never used, neither require … caps of such size and configuration’. The Soul Cap was approved officially in 2022.

In some states in the US, legislation is being enacted to counteract the prevalent hair discrimination many people face within workplaces and schools. The CROWN Act , which stands for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural hair, provides protections against race-based hair bias, prohibiting discrimination based on hair texture and protective styles including braids, twists and locs. Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, who has alopecia and is a key sponsor of the Bill, called it ‘a win for public health – especially the health of Black women who are disproportionately put at risk by these (straightening) products as a result of systemic racism and anti-Black hair sentiment’. As the CROWN Act is not a Federal Act, a DOVE 2023 workplace research study still found that, despite some progress over the past few years, race-based hair discrimination still remains a widespread issue for Black women in the workplace. A similar call in 2020 for a ‘Black Hair Code’ against hair discrimination in the UK, the Halo Collective, has made little progress at the time of authoring this article.

Some primary and secondary schools across the UK have continued to forbid African textured hairstyles resulting in detentions, suspensions or difficulties for Black children who understandably object, i.e. the case of Ruby Williams. The Open University’s Sas Amoah wrote and directed an excellent OpenLearn interactive film piece ‘Good Hair, Perceptions of Racism’, exploring how hair racism manifests itself in schools and workplaces. In 2023 Sas’s film won a prestigious award, the Jury Prize for best short film that explores social Issues, at this year’s International Black and Diversity Awards in Canada. I strongly encourage you to engage with this important and fabulous educational piece.

Hair it is

Today there is an increasing emergence of Black women of all ages who are ‘transitioning’ from using chemicals to straighten their hair to wearing their hair naturally in a myriad of styles. Michelle Obama, now wearing braided and natural hairstyles, has spoken about her experience as First Lady of not being able to do this while in the White House saying in one interview ‘Yeah, we had to ease up on the people’. Having many epithets directed at her over the years including a government official calling her ‘an ape in heels’, Michelle Obama knows what every other Black woman on the planet knows – that no matter how wealthy, how educated, or how idolised Black women are, white European beauty standards still shape the way that people are expected to exist in Western civilisation.

While it is just beginning to change, Black women, as they gain power in business and professional settings still face pressure to ‘code-switch’ and abandon Black hairstyles and mask their Black identifications in other ways. While the movement towards natural Black hair and conscious consumerism has gained momentum over the last several decades, oppressive forces still remain. Black women spend three times more money on hair products than their white peers yet are poorly catered for in many parts of the UK. Of the 45,000 hair salons in the UK only 314 are registered to cater for Afro-textured hair. Even in London where Black residents make up twenty per cent of the population, only two and a half per cent of hairdressers specialise in Afro-textured hair. Since the events of 2020, the National Occupational Standard Level 3 hairdressing qualification now includes the cutting and styling of Afro and textured hair. In 2020, when a UK mixed heritage girl wanted to donate her hair to the Little Princess Trust, a charity that uses donated hair to make wigs for cancer experienced children, they could not accept it as they did not have the techniques and expertise to deal with Afro-textured hair. In the same year, when her son also wanted to donate his hair but found this was not a possibility, mum Cynthia Stroud set up a charity called Curly Wigs for Kids where African textured human hair wigs could be made and has become an ambassador for the Little Princess Trust.

Research suggests (i.e. King and Niabaly, 2013) that the ongoing work of understanding how Black female professionals navigate mostly white organisations means that Black women are subject to both hypervisibility, being scrutinised about everything from the work they do to how they look when doing it, and invisibility in being rewarded for good work. This duality can produce a psychosis for Black women in the workplace trying to fit into corporate structures with the ‘right’ look. Comments I have been subject to over the years such as ‘is your hair real?’, ‘mixed race people have the best hair’, ‘you look like Diana Ross’ (when my hair was long), ‘where has your hair gone?’ (when I cut it), ‘oh, I’m sorry about the cancer’ (when my hair was a ‘Number One’ on the clippers) or ‘wow, your hair isn’t like a Brillo Pad’ (having touched my hair without permission). Similar comments to Black women are sadly common.

It’s not to say that one cannot comment positively on someone’s hair – who doesn’t like a bit of a lift? My hair is pink at the moment – you can’t ignore that – I certainly don’t mind the ‘Girl Fanning’ I’ve had from some colleagues. This is not the problem at all. For Black women, when it becomes about unwanted commentary or cracking jokes about the many hair switch ups of wigs, weaves, braids, locs, shaved or otherwise rather than learning about African diasporic cultures and hairstyle craft – it is microaggressive.

Let us celebrate Black women’s hair with respect and admiration for the hair that grows naturally out of their heads! Does a Black woman, like other women, not have the freedom of choice to wear her hair how she chooses? Think about why someone is compelled to ask the question ‘can I touch your hair?’ and then be shocked at the answer!

Good reads are Emma Daribi’s books Twisted: The Tangled History of Black Hair Culture, ‘Don’t’ Touch My Hair and great watches are the beautiful Oscar winning animation ‘Hair Love’ and this YouTube history of Black women’s hair journeys piece.

It's time that Black women feel safe and empowered to wear our hair however we’d like without the accompanying think pieces and discourse. Hair discrimination continues to be a pervasive issue that impacts Black women’s experiences in the workplace and wider society. As with any type of bias, it’s important to continue to have conversations that centre the experiences of those most impacted while providing ongoing education for others.

*in this article for simplification I use the term ‘Black’ interchangeably with ‘African textured’ or ‘Afrocentric’ to describe/explain the political significance of hair or cultures for African diaspora peoples.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews