Background: police violence against black women

In response to the death of George Floyd who was killed in 2020 by a US police officer kneeling on his neck, despite protestations of not being able to breathe from both himself and onlookers, the Black Lives Matters (BLM) movement became prominent in the public imaginary across the globe.

Between 2015 and 2020 in the US, forty-eight black women had been killed by the police, yet only two charges have been brought against their assailants.The original movement emerged in 2013 as a result of three black women – Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi – responding to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for killing the black teenager Trayvon Martin. While this acknowledgement of BLM was a positive sign for those who champion social justice in terms of greater recognition, one aspect it did reveal was the gender inequity in regard to the publicising of deaths by police using excessive force. Before this time, the lives and experiences of black women and their relationships with the criminal justice system, in particular the police, remained virtually hidden. It was argued by Jamila Aisha Brown (2013) that had Trayvon Martin been a woman, we would have never heard about ‘her’ because the ‘lives of black women are valued little by white society or the black community’. This highlights how black women have been ignored and side-lined in these discussions.

Between 2015 and 2020 in the US, forty-eight black women had been killed by the police, yet only two charges have been brought against their assailants (NYTimes, 2020). With this in mind, it has been suggested that the true number is not known due to the hidden nature of police violence and black women. Such information is extremely difficult to access (Jacobs, 2017). There is also very little academic literature that focuses on the experiences of black women and police brutality in the US. However, one notable exception is ‘Invisible no more: Police violence against black women and women of colour’ by Andrea Ritchie (2017). Ritchie embarks upon painstakingly detailed research into the violent and fatal encounters experienced by black women, bringing attention to cases such as those of Sandra Bland and Rekia Boyd. She highlights the relative invisibility of cases like this when it comes to not only those in academia but also in terms of what captures the media’s attention, the response (or lack) of policymakers and the general public. Sandra Bland died of asphyxiation in police custody, yet her death was ruled as suicide by police which was challenged globally and by the #SayHerName movement. Rekia Boyd was shot and killed by an off-duty police officer, Dante Servin, who fired from his car into a group of young people following a verbal exchange with them. Rekia Boyd was struck in the head. The police officer was charged with involuntary manslaughter but was later acquitted. Cases like these were to galvanise the BLM movement and began an acknowledgement that it’s not only black men who experience police brutality.

The experience in the UK

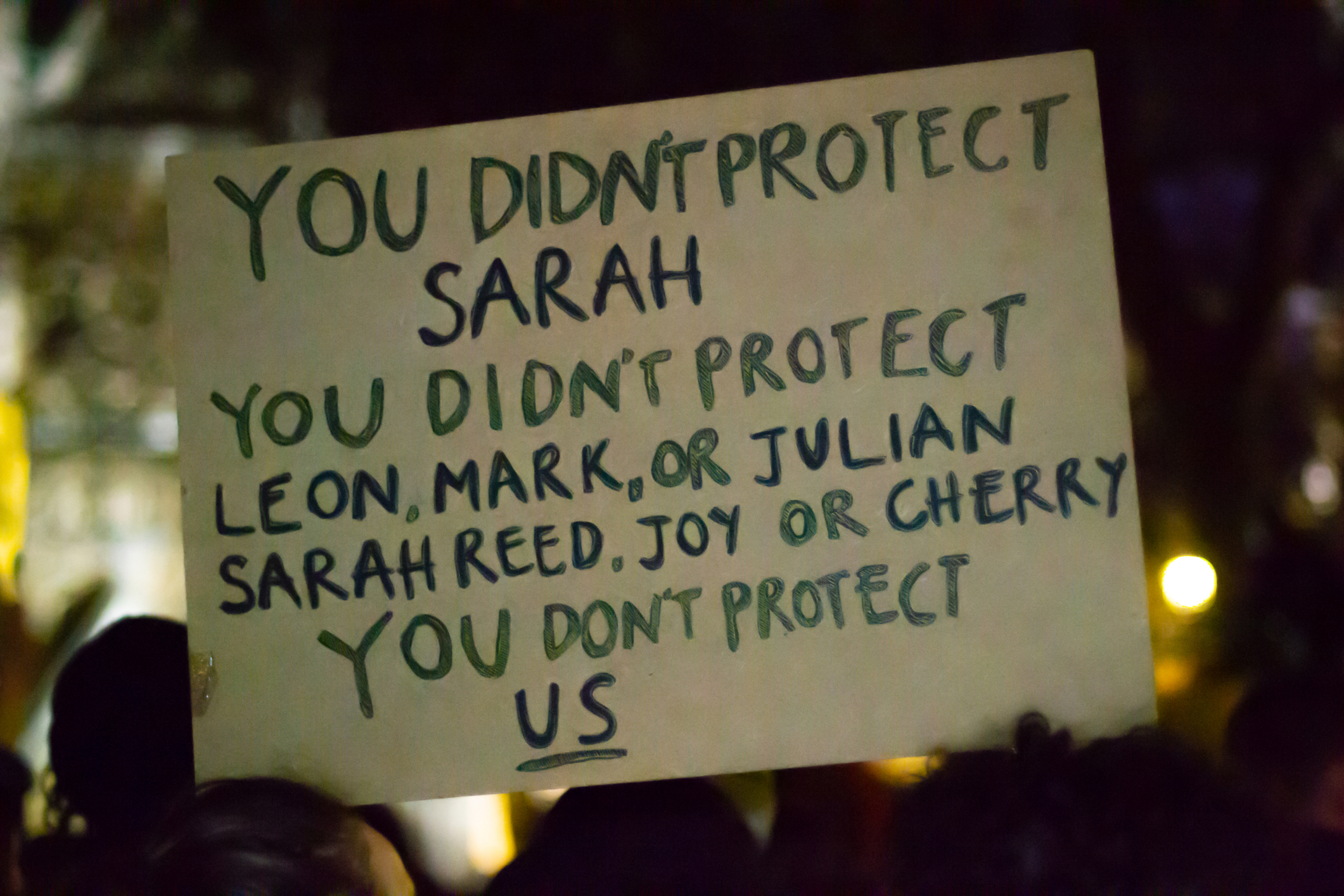

By 2015, the first Black Lives Matter movement in Europe had started up in England. In Lambeth, the names of 3,000 BAME people who had died in police custody, prisons, immigration detention centres and racist attacks in the UK were listed on a billboard. It spells out ‘I can’t breathe’ in homage to George Floyd’s last words to bring attention to those who have died as a result of racial violence.

That racism and police brutality are also a feature of UK society was highlighted in the renewed interest in the BLM movement in 2020, as it’s often assumed by people in the UK that racism is something that happens elsewhere in countries like America. Co-founder of the UK BLM movement, Natalie Jeffers (quoted in McVeigh, 2016), stated that ‘we have dozens of British families left fighting for justice over their loved ones suffering state violence, so we know there’s a problem in the UK…In Britain, somebody dies every six days in police custody, not just Black people. But Black people are over-represented in these cases’. Also noted by Kojo Koram (2020): ‘those who argue that Black Lives Matter protesters are jumping on an American bandwagon wilfully miss the point’. Koram also makes the important point that the last time a police officer was successfully prosecuted in the UK regarding the death of somebody in custody was in 1969.

The case of Sarah Reed

Within the context of the UK, black women and their encounters with the police, Sarah Reed’s case draws attention to the extent to which this is a significantly worrying issue in the UK. In 2012, Sarah was the victim of police brutality. Police officer James Kiddie was found guilty of assaulting her during a shoplifting allegation. He was seen on CCTV grabbing her by the hair, punching her and kneeling on her back as she lay on the floor of a London shop. He was later dismissed from the force and sentenced to a 150-hour community order for common assault (BBC News, 2016). In a 2014 interview with Channel 4 News (2014), Sarah said that the incident had a profound effect on her life and contributed to her mental health issues.

In 2015, Sarah Reed, who had a history of psychotic episodes, while being treated at a secure hospital for her mental illness, claimed that she had been sexually assaulted and had fought back to defend herself. She was subsequently charged with wounding with intent. Initially, she had been ‘bailed and under the care of a community mental health team while her trial was heard’. However, she was then placed on remand at Holloway Prison. In response to the charge against her, she stated that she was simply defending herself but ended up becoming labelled a perpetrator which resulted in her being imprisoned. Tragically, she died due to the neglect and ill-treatment of the prison and healthcare staff at Holloway who failed in their duty to provide ‘…adequate treatment for her high levels of distress, and the failure of prison psychiatrists to manage Sarah’s medication’ (Inquest, 2017). It was known that Sarah had been exhibiting psychotic disorder, bipolar, schizophrenia and bulimia, yet monitoring had been reduced, which gave her the opportunity to strangle herself in her cell. She spent her final days alone in a dirty cell without access to contact with her family.

The tragic sequence of events that led to Sarah’s death supports Michelle Jacobs’ (2017) point that black women tend to be positioned as perpetrators of violence rather than victims. While INQUEST in 2017 accepted that Sarah’s death had been ‘self-inflicted at a time when the balance of her mind was disturbed…they were not convinced that she intended to take her life’ (Inquest, 2017). So what we have here is a young woman who had mental health issues, had experienced the heartbreak of her daughter’s death, been a victim of police violence and sexual assault but yet it was decided that the best course of action was to imprison her. When she died it was reported that prison officers were told to delay calling an ambulance and her family were not able to see her body for three days while being given conflicting information about what had happened to her (Revesz, 2017).

The tragic case of Sarah Reed is an example of how women can be killed by the state through structural violence, with Sarah being a victim of this and interpersonal police brutality. James Gilligan defines structural violence as the ‘main cause of behavioral violence on a socially and epidemiologically significant scale (from homicide and suicide to war and genocide). The question as to which of the two forms of violence—structural or behavioral—is more important, dangerous, or lethal is moot, for they are inextricably related to each other, as cause to effect’ (Gilligan, 1997). The importance of structural violence compared to interpersonal violence cannot, and should not, be overlooked in terms of its impact; that major institutions of the state, such as the police, have been regarded as institutionally racist means that certain groups are even more at risk. It was a catalogue of errors that meant a mentally unstable woman was imprisoned for defending herself. In 2016, Sarah’s mother, Marylin Reed, stated that ‘my daughter was failed by many and I was ignored’ (quoted in Gentleman and Gayle, 2016). This was despite Sarah suffering from a range of mental health issues known to prison officers, doctors, social workers, lawyers and police.

Sarah should never have been remanded to Holloway prison, and the fact that the lack of care that she experienced in this institution led to her suicide demonstrates the impact of the intersection of oppressive social factors.Sarah should never have been remanded to Holloway prison, and the fact that the lack of care that she experienced in this institution led to her suicide demonstrates the impact of the intersection of oppressive social factors. In this case, the fact that Sarah was working-class, young, female and black, certainly played a large part in her lack of treatment and care within the institutions she was confined in. This treatment and attitude can be seen as indicative of those who engage with both mental health services and criminal justice services. The lack of care and understanding towards black women, particularly those who are working class, has also been played out within British criminology who have continually denied and failed to acknowledge the lives and experiences of women of colour (Choak, 2020). We know extremely little about their engagement with the criminal justice system even though they are a growing number proportionally within this system. As recently as 2020, a 28-year-old black woman was held down by six police officers and hit repeatedly while she shouted out that she could not breathe; once taken to the police station she was subjected to a strip search experiencing further police brutality and humiliation (Dodd, 2020). Charges against her were dropped. One of the many concerning features of the approaches used by the police and the Criminal Justice System (CJS) is the somewhat dehumanising way in which black women are subjected to such treatment which is systematically rooted in racism.

Women like Sarah Reed can, and should, never be forgotten. Within the course Understanding criminology at The Open University, her case has been highlighted as an example of both structural violence and how intersectional forms of oppression can work to cause deaths in custody of vulnerable women.

Deborah Coles, Director of INQUEST surmised that:

‘Sarah Reed was a woman in torment, imprisoned for the sake of two medical assessments to confirm what was resoundingly clear, that she needed specialist care not prison. Her death was a result of multi-agency failures to protect a woman in crisis. Instead of providing her with adequate support, the prison treated her mental ill health as a discipline, control and containment issue…The legacy of Sarah’s death and the inhumane and degrading treatment she was subjected to must result in an end to the use of prison for women. The state’s responsibility for these deaths goes beyond the prison walls’ (Inquest, 2017).

What cases in the US and UK show is that police violence against women is an everyday concern and reality, but it is an issue that is still quite invisible. Recent cases relating to deaths at the hands of serving police officers has shone a spotlight on what is a real and significant problem that can no longer remain swept under the carpet and covertly dealt with behind closed institutional doors.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews