Find out about The Open University's law courses.

History

The English discovery of Barbados occurred in 1625 and it was settled in 1627. I use ‘discover’ in the context of England discovering the island, as opposed to it being discovered as an island. Despite evidence of indigenous populations having been present in Barbados in the past, including Caribs and Arawaks, a visit by the Portuguese in 1536 confirmed the island uninhabited (Hoyos, 1978, p. 14). Slaves came with the first settlers in 1627 and Barbados became a slave society from the mid-seventeenth century (see Beckles, 2017). Slavery was abolished in 1834 (when the Emancipation Act 1833 came into force), Barbados became independent in 1966 (with the Constitution of Barbados 1966) and a Republic in 2021 (with the Constitution Amendment Bill 2021).

Barbados was uninhabited upon discovery, which afforded those who discovered it freedom to create a society from scratch. Following this, the English Crown assigned Barbados “proprietary status”, which treated land “as a possession of a particular person” (see Elson, 1904) affording great power and control to an individual (or syndicate).

Such circumstances enabled explicit focus to be on wealth expansion and economic exploitation. Early agricultural production centred on tobacco and later cotton which proved unsuccessful. In need of an alternative crop, and with the assistance of the Dutch, Barbados began harvesting and cultivating sugar cane. And this was the game changer. The exponential growth in demand for sugar coupled with the autonomous, finance-driven economy that had been created worked together to ensure vast financial success for those who were invested in the island. With this boom in the demand for sugar came the use of slavery (Knorr, 1944, p. 12).

Operation of Slavery

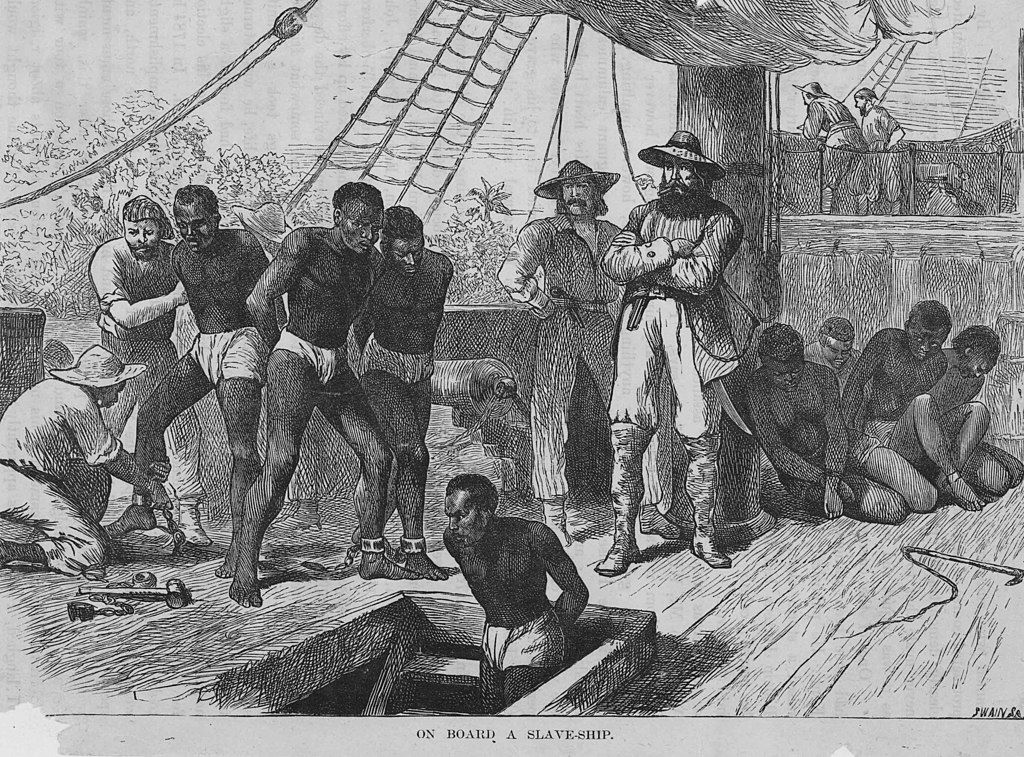

Owing to its geographic location, a large number of those arriving in Barbados came via the Middle Passage (the route from West Africa across the Atlantic Ocean). The horrors of the Middle Passage are well documented – slaves were restrained below deck for the majority of the journey, and there was a lack of sanitation, lack of sustenance and high prevalence of disease. In the 1750s, records show that one in five Africans on board slave ships heading for the America’s from Africa died.

Slaves aboard a slave ship being shackled before going into the hold. A wooden engraving by Joseph Swain, circa 1835.

Slaves aboard a slave ship being shackled before going into the hold. A wooden engraving by Joseph Swain, circa 1835.

For those who survived the journey, a (short) life of slavery awaited (Steckel, 1979). Slavery was not practiced in England, meaning there were no laws to import that would govern it. To overcome this, settlers relied on the law of property (Hobbs). Slaves were classified as private property over which owners claimed absolute authority (Handler, 2016, p. 240; Cowles, 2016, p. 151). Core features of slavery included the following:

-

Being property for life, with status passed through the mother. (Regardless of whether the father was free, enslaved or indentured. Unless they were manumitted, which was a rare occurrence in Barbados slave society and particularly rare in the seventeenth century).

-

They could be bought, sold, bequeathed in wills, given as gifts, used to pay mortgages, as loan security, listed in inventories (along with other moveable property and livestock), and their value specified in currency or sugar (Handler, 2016, p. 240; Morgan, 2004).

-

Sexual exploitation, extreme levels of violence as punishment, the separation of families, barring of access to Christianity and restrictions on cultural development.

By 1670, slaves comprised of three-fifths of the Barbados population, and by 1700, three-quarters (Galensonn, 1982).

Abolition

The slave trade was abolished in 1807 (Slave Trade Act 1807). The practice of slavery continued until 1834, abolished by the Emancipation Act 1833. The Act compensated slave owners for their loss of property and implemented an apprenticeship scheme which required ex-slaves to continue working and living on plantations for low wages, under the guise of being trained to be free.

Reparations

Reparations are a form of damages given as acknowledgement of fault in past action. Although traditionally spoken about in compensatory/monetary terms, they can be in the form of land, rights, guarantees, etc.

The CARICOM Reparations Commission is a regional body created to establish the case for reparations to the Caribbean Community for the “Crimes against Humanity of Native Genocide, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and a racialized system of chattel Slavery”.

The Committee developed a 10-point plan, calling for:

- Full apology

- Repatriation

- Indigenous people’s development program

- Cultural institutions

- Public health crisis (action)

- Illiteracy eradication

- African knowledge program

- Psychological rehabilitation

- Technology transfer

- Debt cancellation

The (brief) arguments

For:

-

Slavery created vast amounts of wealth for the colonisers, the planters and the white elite (see Williams, 1944)

-

Continuing legacy of slavery (inequality of land distribution and wealth distribution)

-

Compensation paid to slave owners

-

Slavery is endemic in economic and political structures

Against:

- Source of funds

-

Hereditable guilt vs hereditable virtue

-

Retrospective application of laws

-

All colonised states to be compensated?

Opinion

The reality is much more nuanced than these basic arguments, and, in my opinion, we can’t even begin to have a structured, coherent debate on reparations until we consider the narrative around Britain’s past. This, I argue, has become all too obvious in the Colston 4 case (R v Graham & Ors [2022] Bristol Crown Ct (unreported). A few newspaper headlines are included in the presentation which illustrate how, for some, the case was interpreted. Debates on talk radio at the time centred on the erasing of history, the reality of our history, and the positives to be garnered from empire and colonisation. This chimes with Niall Ferguson’s text, Empire (2004), described in a Guardian review as offering:

...... a bracing corrective to those cruder critics who persist in analysing the empire only in terms of racism, violence and exploitation. He draws attention, as others have done, to its episodes of idealism, creativity and administrative integrity, to its many examples of overlap and collaborations between different peoples, and above all to its historical context. He is almost certainly correct in arguing that the alternative to Britain's global inroads would not have been a pure, unsullied world, but rather the emergence of other empires that might have been worse.

The presentation includes a quote from Sathnam Sanghera, which discusses the nostalgic, often romantic, manner in which colonisation is viewed in Great Britain. This chimes with the cited YouGov poll of 2020, which found that:

-

More than 30% of British people were proud of the Empire

-

1/3 people in the UK believed that Britain’s colonies were better off as part of an empire

-

Britons were more likely to say that they would like their country to still have an empire than those from 7 other coloniser states.

In my opinion, the narrative, presentation and associated sentiment surrounding empire, colonisation and imperialism is far from where it would need to be in order to garner sufficient public support and momentum to enable a successful and fruitful discussion on reparations.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews