The Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) is an opportunity for you to work independently on a topic that really interests you or that you think is important. It is equivalent to an A-level qualification. These articles are designed to help you if you are enrolled on an EPQ.

See previous article in series: Designing your research question

Before working through this article, you should have settled on your research question.

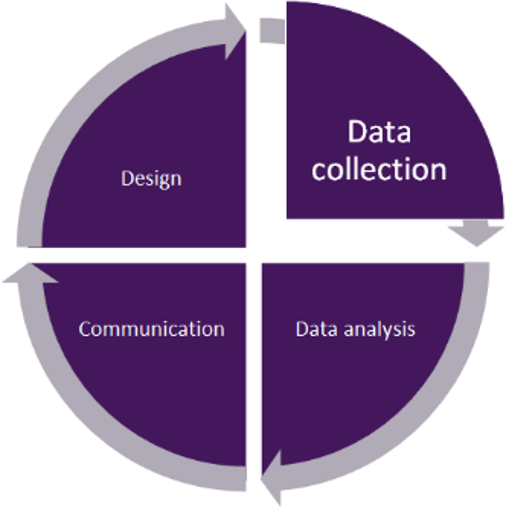

This article will support you through the next steps in the research cycle (Figure 1): collecting evidence (or data) to help you answer your question and starting your analysis of that evidence. First, let’s look at collecting data.

Figure 1 The research cycle: data collectionAn illustration of the research cycle, represented by a circle divided into four segments. Around the circumference of the circle are arrows indicating this is an ongoing process. The four segments are (clockwise) design, data collection, data analysis and communication. The data collection segment is highlighted.

Figure 1 The research cycle: data collectionAn illustration of the research cycle, represented by a circle divided into four segments. Around the circumference of the circle are arrows indicating this is an ongoing process. The four segments are (clockwise) design, data collection, data analysis and communication. The data collection segment is highlighted.

What is already known about your topic?

The first step in answering a research question is usually to do a ‘literature review’ or ‘research review’.

These articles focus on the ‘research review’ type of EPQ, in which collecting and analysing evidence from what other people have written will be a major part of what you do.

Researchers need to do research reviews for two reasons. First, they want to uncover what is already known. A lot is already known about some topics and they want to be sure that they are researching a novel question. Second, they want to get a balanced view of what is known, rather than jumping in and relying on the first pieces of information they find.

Figure 2 Julia, a planetary scientistA photograph of Julia.

Figure 2 Julia, a planetary scientistA photograph of Julia.

A literature review starts with focused and serious reading, to help you develop your knowledge and understanding of the topic, and begin to gather evidence that will help you answer your question.

Julia, a researcher in AstrobiologyOU, whose research explores the possibilities for habitable environments in the Solar System, demonstrates how she starts a literature review. As you read through, think about the process Julia describes and how you could apply the steps she takes to your EPQ research review.

When you’re starting a literature review, where do you look for evidence?

Any literature review requires a well-defined topic. Let’s assume the topic is something in planetary science!

Find an exciting topic: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov provides a good overview of our Solar System. Let’s pick Mars.

Figure 3 A photograph of Mars taken from orbit

Figure 3 A photograph of Mars taken from orbit

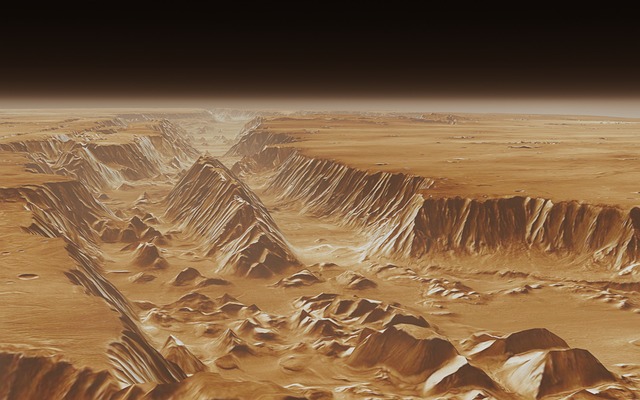

Define a specific question. How did Valles Marineris form?

Figure 4 Valles marieneris, MarsAn illustration of Valles Marineris, Mars. Valles Marineris is a system of canyons on Mars. It is more than 4,000 km long, 200 km wide and up to 7 km deep.

Figure 4 Valles marieneris, MarsAn illustration of Valles Marineris, Mars. Valles Marineris is a system of canyons on Mars. It is more than 4,000 km long, 200 km wide and up to 7 km deep.

Learn about Valles Marineris. You can use Wikipedia as a starting point and look up the references given there.

Use Google Scholar to find specific literature (e.g. search words such as *formation of Valles Marineris*). Look up research cited in the papers you read if they are also relevant to your topic. Make sure you always cite your sources.

Finding keywords.

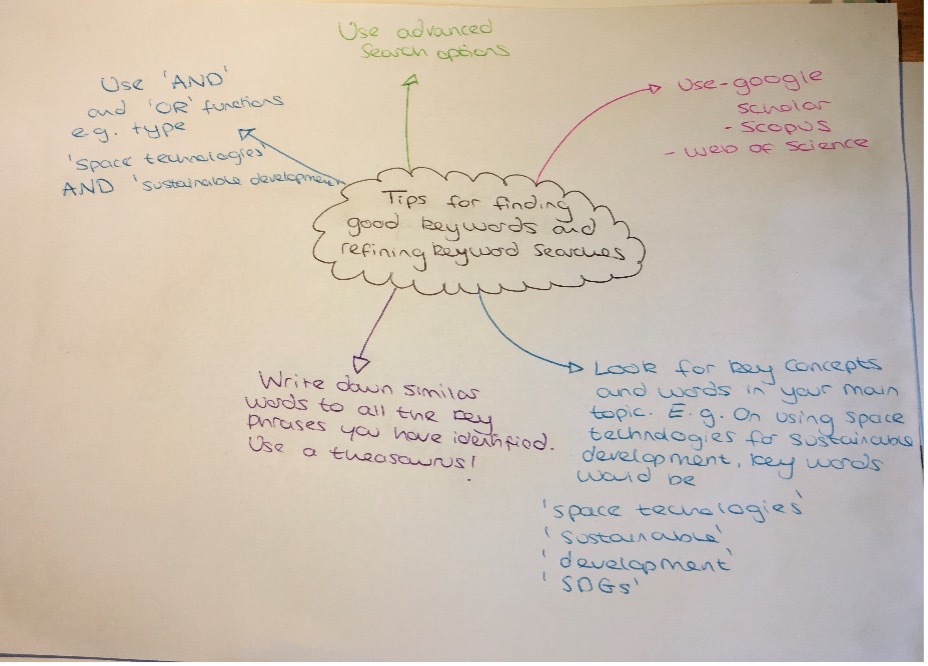

With so much information available online, how do you begin finding relevant material? Most researchers start by assembling a collection of keywords that relate to the topic and can be used to search for more information. But how do you find those all-important keywords?

In some ways, deciding on your keywords is like the ‘ten words’ activity you used in Article 1 to help you move from topic to question.

One way of identifying keywords is to start with the ‘big idea’ and gradually work your way in. There are lots of different ways to do this. As an example, Devyani, a PhD student with AstrobiologyOU, made a short video to show how she creates a mind map (Figure 5) to identify keywords before starting her literature search. Figure 6 A heap of possible keywordsAn illustration of a heap of small tiles or pieces of paper, each with a single word printed on it.

Figure 6 A heap of possible keywordsAn illustration of a heap of small tiles or pieces of paper, each with a single word printed on it.

You might want to try Devyani’s method, or you could try this quick activity from The Open University to get started on finding good keywords.

Going back to the example research question we used in Article 1: ‘How did young people use social media for activism?: comparing the content of Instagram posts on #blacklivesmatter and #FridaysForFuture during 2020’

What keywords might you use to search for relevant material to help answer this question? Perhaps you’d come up with ideas like “social media”, “activism”, “black lives matter”, “Fridays for future”.

As you can see, keywords can sometimes be more than one word!

Searching for evidence.

Having identified your keywords, the next step is to use them to start searching for evidence that will help you answer your research question.

Evidence can come from many sources: books; academic articles (often called ‘papers’); reports from businesses, charities and other organisations; newspaper articles; radio and television; websites; social media … the list could go on!

With so much material out there, it’s helpful to make a plan before you start your search. Think about:

- the keywords you will use

- the most useful places to search

- the time you have available for searching.

Keeping track.

You will gather a lot of information, so you should keep good records. Knowing what you’ve looked for, where you looked and what you found there will help you avoid repeating something you’ve already done. You’ll also be able to fully acknowledge the sources you have used in your research (this will be discussed further in Article 3). Make notes of:

- what keywords and combinations of keywords you used (your ‘search terms’)

- where you looked

- what documents you downloaded or read online

- notes you made about what you read.

You could keep a record in a simple table, perhaps on a spreadsheet (you can download an example here).

For any documents you find, you’ll also find it useful to keep records of:

- the name of the author(s)

- when it was published

- the title of the article, report, book or chapter

- where it was published – i.e., the title of the journal, book or website

- a link to the document or its DOI (digital object identifier)

- (for books) the name of the publishing company and where it’s based.

The digital object identifier (DOI): You might not have come across a DOI before. Most academic articles have a DOI – a unique string of numbers and letters that is permanently attached to an article. If you paste a DOI into a browser, it will take you straight to that article. Try this one: https://doi.org/10.14324/RFA.05.2.14

When it comes to writing up your dissertation, these notes can be good evidence in themselves, showing how you carried out your review, so it’s sensible to get your record-keeping method set up before you begin searching.

Where should I search?

It’s very likely that you will carry out your search using online resources. But there are so many to choose from that it can be difficult to know where to start.

You can use the well-known search engines, such as Google, Bing or Yahoo, but you will get more reliable results if you use a specialised search engine such as Google Scholar, which returns links to articles and academic papers produced by researchers in universities and research institutions.

Many of the papers, articles, newspaper pieces and other items that you will find in your searching – but not all – will be open access, which means they are free to view and you can download them.

Many universities have

repositories that store the work of researchers at that university. The Open

University’s repository is called Open Research Online (ORO). Most UK and international universities have something similar. Universities

maintain these repositories because they want to make the work of their

researchers available for others to use.

Repositories are often looked after by the university’s library team, so if you can’t find the repository easily, try looking on the library pages on the university website.

Online repositories usually allow you to search by a topic, or by the name of the author if you are trying to get hold of a particular resource.

If you’re interested in the work of a particular research group (such as AstrobiologyOU) or a specific researcher, you’ll often find them on social media. Most research groups keep copies of work published by their researchers; it’s always worth contacting them. Explain that you want to use the research for your EPQ.

Researchers often have their own websites (here’s an example), which you can find using a search engine. If you can’t get hold of an article that you need for your work, email the researcher. Researchers are often willing to share copies of their work to help other researchers, so explain that you want to use it for your EPQ.

Many researchers keep copies of their papers and articles on networking sites such as ResearchGate, which also allow you to search by topic. However, these records are kept up to date by the researchers themselves, so you should always check against another source if you can.

Professional databases, such as Web of Science and EBSCO, bring together

research from thousands of researchers across the world.

However, you will have to create an account, or pay a subscription to make full use of sites like this, which might not be practical for you.

If you find the researcher on the database but the paper you want isn’t there, use the database’s facilities to contact the researcher. Again, tell them why you want to read the article.

Universities and research institutions are increasingly bringing their resources together into large collections.

CORE is the world’s largest collection of open access research papers and articles.

ARXIV.org has more than a million articles, mainly in physics, mathematics and engineering.

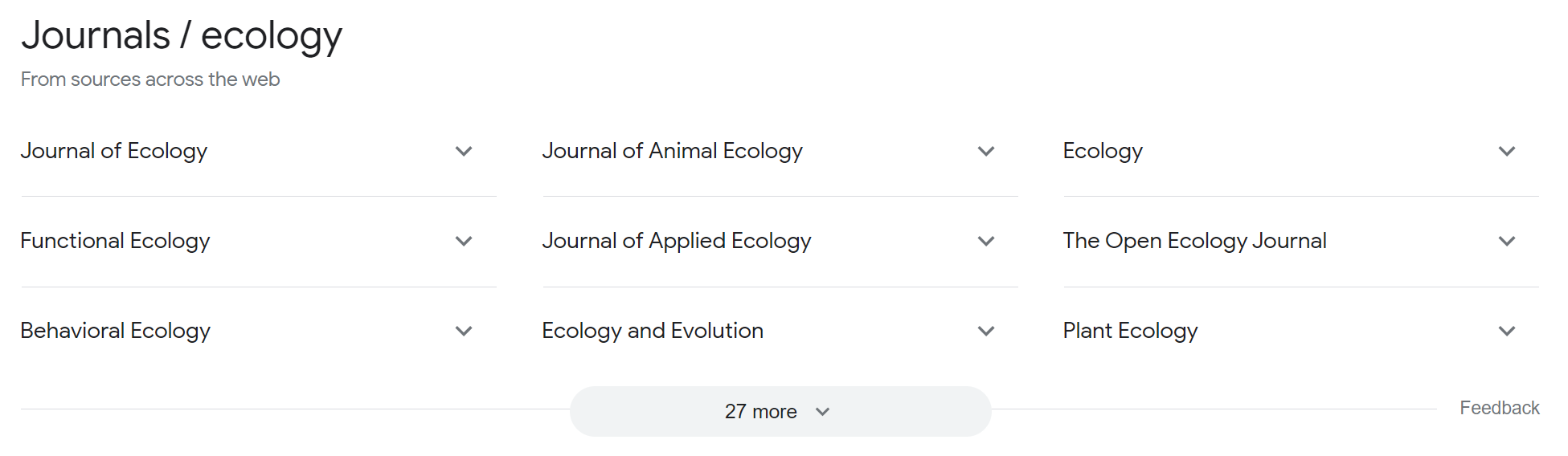

Figure 7 Results of searching for "ecology journal"A screenshot of the results of a search for the term "ecology journal" on Google. The titles of nine journals with the word ‘ecology’ in the title are shown, and a label shows there are at least 27 further results available.

Figure 7 Results of searching for "ecology journal"A screenshot of the results of a search for the term "ecology journal" on Google. The titles of nine journals with the word ‘ecology’ in the title are shown, and a label shows there are at least 27 further results available.

Journals are the places where researchers publish the articles that discuss their research. There are many thousands of academic journals in existence, covering every topic imaginable.

For example, try typing the phrase "ecology journal" (complete with speech marks) into a search engine. You will find a long list of possible titles is returned.

On the journals’ websites, you can search by topic to find relevant articles. If you are searching for a specific paper, and know the journal it was published in, you can use the journal’s search function to find it. However, many journals are commercial organisations and keep articles behind a ‘paywall’, meaning they are only available to people or institutions that subscribe to them.

Fortunately, more and more journals (for example PLoS – Public Library of Science) are fully open access and many journals make some articles freely available.

Print media: If you’re looking for material published in newspapers or magazines, first try the website of the newspaper or search for their digital archive. If you can’t find it online, try your local public library; they often have access to hard-copy archives or can advise you where to find them.

Book publishers: There are many academic publishers, such as Ubiquity Press, that produce open access books you can download.

Organisations: research funders, such as the Wellcome Trust, make available copies of papers and reports written by their researchers. Other organisations’ websites, such as those from the government or charities, often have copies of project reports or annual reports available.

Public libraries: Finally, don’t forget your local public library. Even if they don't have the exact article or book you’re looking for on the premises, they have trained librarians who can help you find it or suggest alternative routes to get the information you need.

Refining your search.

Even if you use very specific keywords, an online search might return hundreds, if not thousands of results. How can you cut hundreds of results down to a sensible level?

Focusing and refining the keywords you use for your search will help you be realistic, making the best possible use of the limited time you have available for the EPQ, and cutting down your results to an amount that you can realistically deal with.

Figure 8 Michael, a researcher in AstrobiologyOUA photograph of Michael.

Figure 8 Michael, a researcher in AstrobiologyOUA photograph of Michael.

Here are Michael’s key tactics for refining your searches:

- Linking several search terms to narrow down your search.

- Starting broad and then refining – he used a personal example where he started by looking for ‘bacteria associated with plants’ and narrowed down to ‘bacteria associated with peas’.

- Keeping track of your topics and sub-topics with a list, spreadsheet or mind map.

- Remembering you don’t have to read every single resource you find.

Practising searching using Google Scholar.

Google Scholar is a freely-available search engine that only returns links to scholarly literature, so it’s a good place to practise your searching techniques.

Imagine that you have decided to research this question:

What are the health benefits of people spending time in nature?

What are the keywords you could use in your search? You might think of:

- health

- nature therapy

- green health

- forest bathing

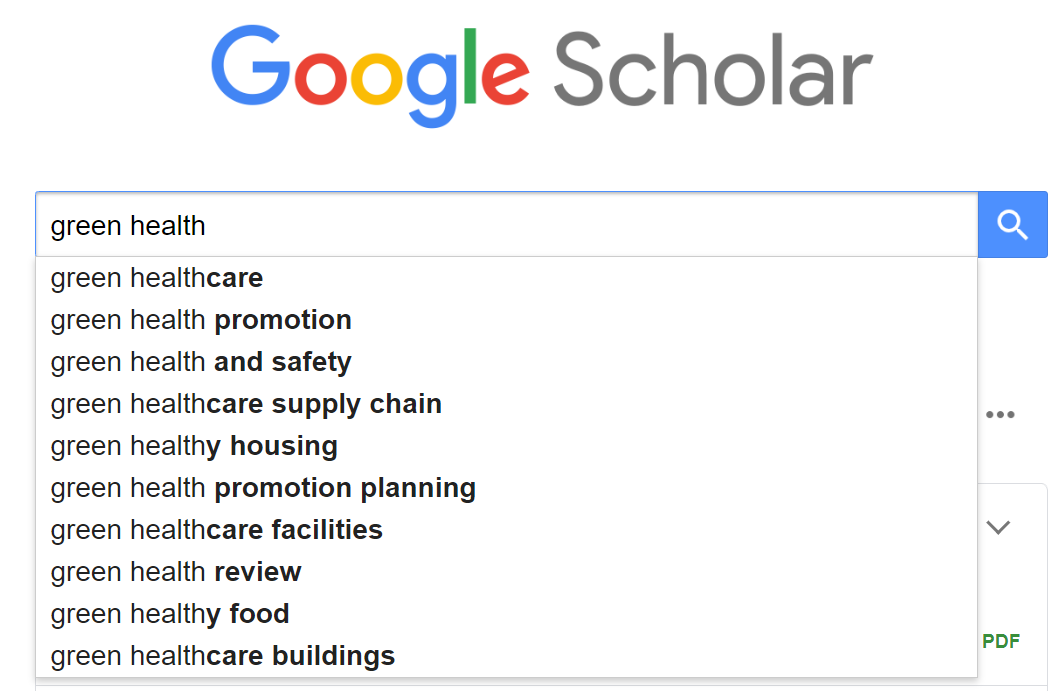

Experiment with entering the search terms into Google Scholar. For example, type the words ‘green health’ into the search box and press enter.

Figure 9 Entering search terms into Google ScholarA screenshot of entering the search terms ‘green health’ into Google Scholar

Figure 9 Entering search terms into Google ScholarA screenshot of entering the search terms ‘green health’ into Google Scholar

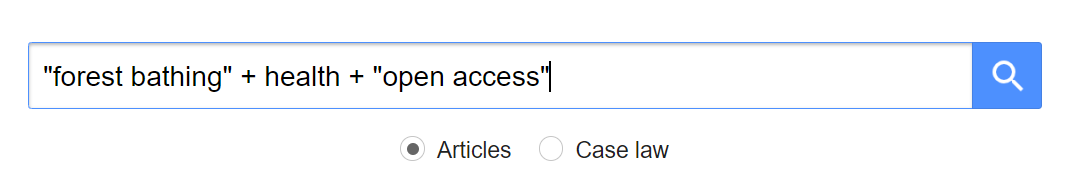

Using a simple search term like this can generate a long list of articles. In this example (Figure 10) it was somewhere around five million, which is far too many for you to review meaningfully!

Figure 10 The result of searching for the term ‘green health’A screenshot of the result of entering the search terms ‘green health’ into Google Scholar. Google Scholar has found more than five million results.

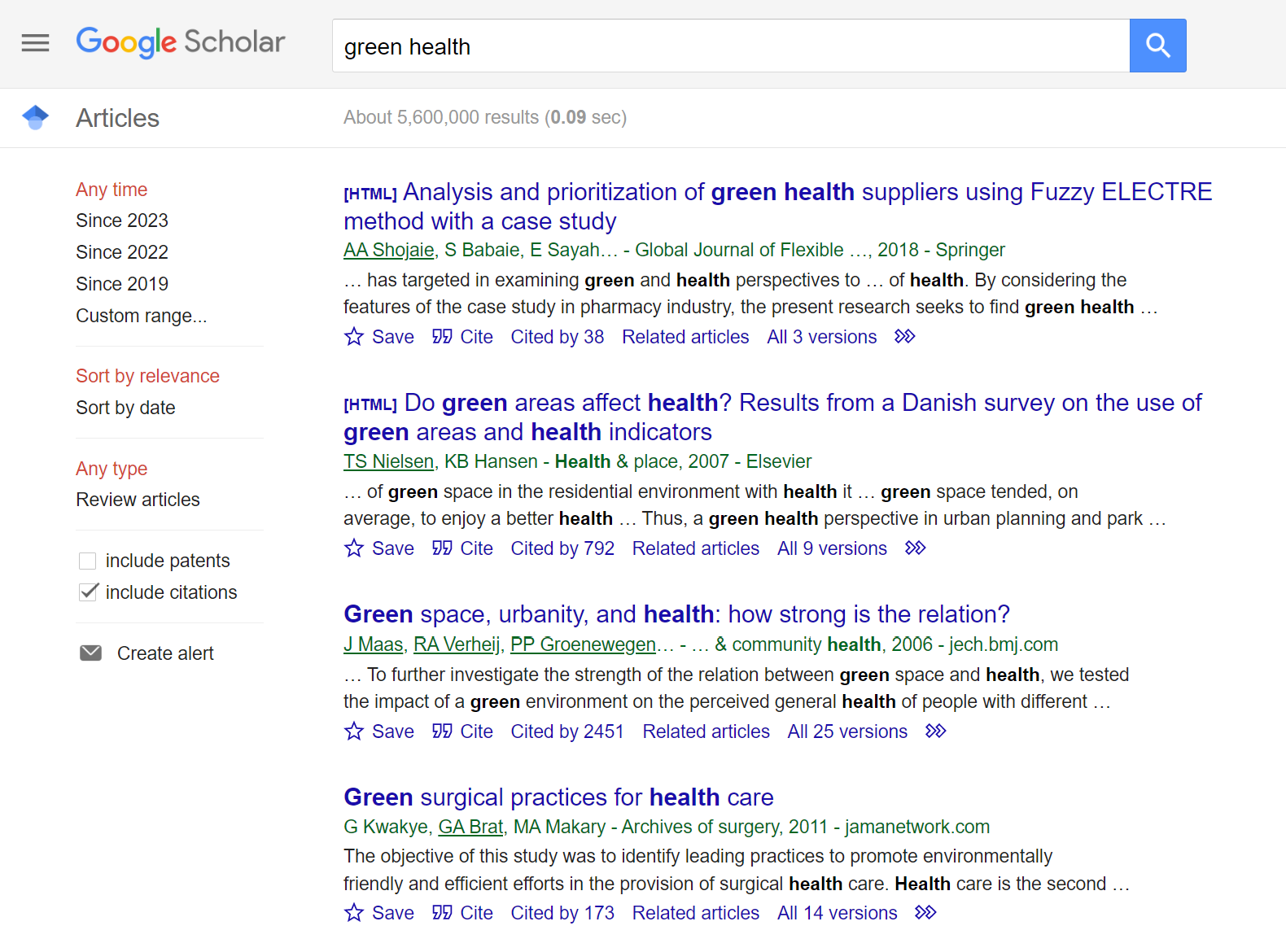

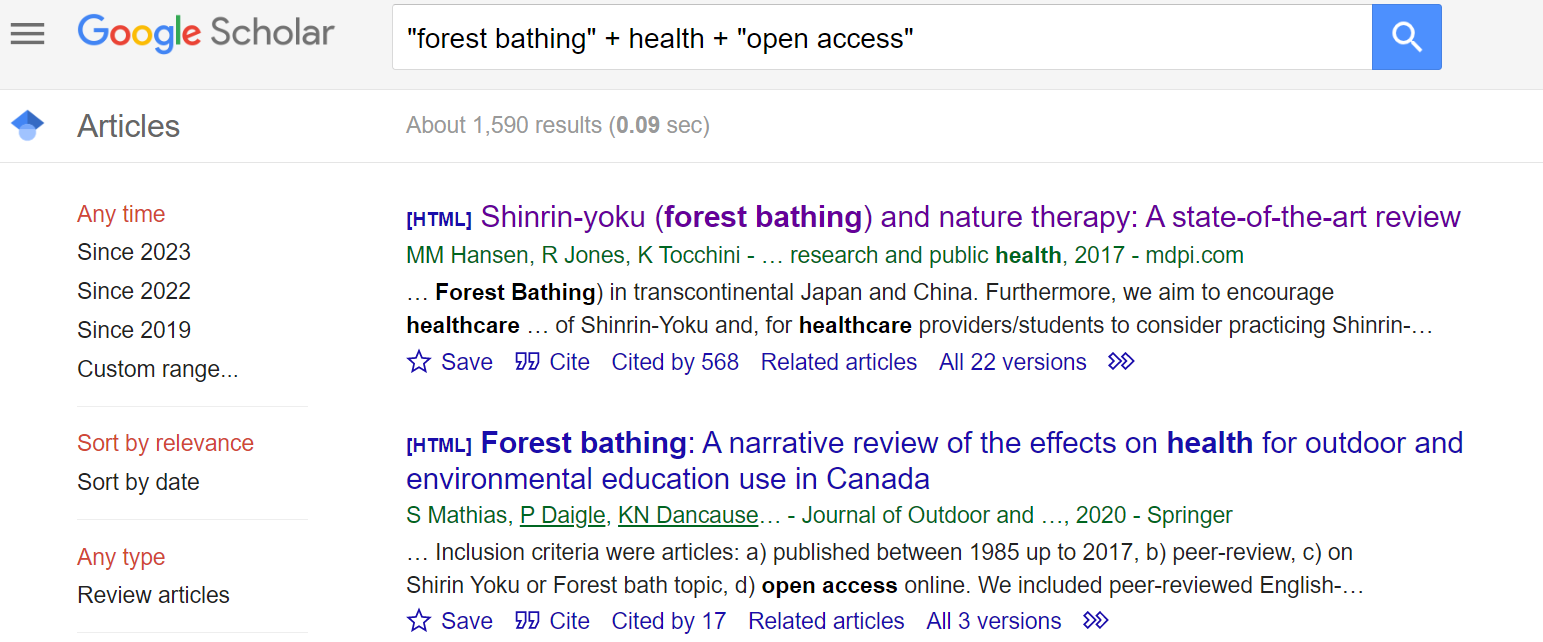

Figure 10 The result of searching for the term ‘green health’A screenshot of the result of entering the search terms ‘green health’ into Google Scholar. Google Scholar has found more than five million results.Combining search terms and using punctuation to keep two or more words together can help you focus your search and return fewer results to look through. Try typing “forest bathing” + health + ”open access” into the search bar:

Figure 11 Combining search terms in Google ScholarA screenshot showing an example of combining several search terms. This search combines "green health" (with speech marks around the whole phrase), followed by a plus sign, followed by the single word ‘health’, another plus sign, followed by the words "open access" (with speech marks around the whole phrase).

Figure 11 Combining search terms in Google ScholarA screenshot showing an example of combining several search terms. This search combines "green health" (with speech marks around the whole phrase), followed by a plus sign, followed by the single word ‘health’, another plus sign, followed by the words "open access" (with speech marks around the whole phrase).

Quote marks (“…”) keep words together. With quote marks (“forest bathing”) the search will return articles about forest bathing. Without them (forest bathing), you’d get articles on woodland and swimming pools (among other things!).

Using the + symbol combines “forest bathing” AND health. Adding + “open access” means you will only see results where you have free access to the full article.

This cuts down the number of results to around 1600 (Figure 12):

Figure 12 Results returned from Google Scholar using refined and combined search termsA screenshot showing the results of the search using combined search terms. This time, Google Scholar has found about 1600 results.

Figure 12 Results returned from Google Scholar using refined and combined search termsA screenshot showing the results of the search using combined search terms. This time, Google Scholar has found about 1600 results.

You can then click on the search results to access the articles. Clicking the top link brings up an article about forest bathing (at time of writing – the top result may well have changed since then).

Figure 13 Top article returned in March 2023 using refined and combined search termsA screenshot of the online article found by the advanced search. The title is ‘Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review’.

Figure 13 Top article returned in March 2023 using refined and combined search termsA screenshot of the online article found by the advanced search. The title is ‘Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review’.

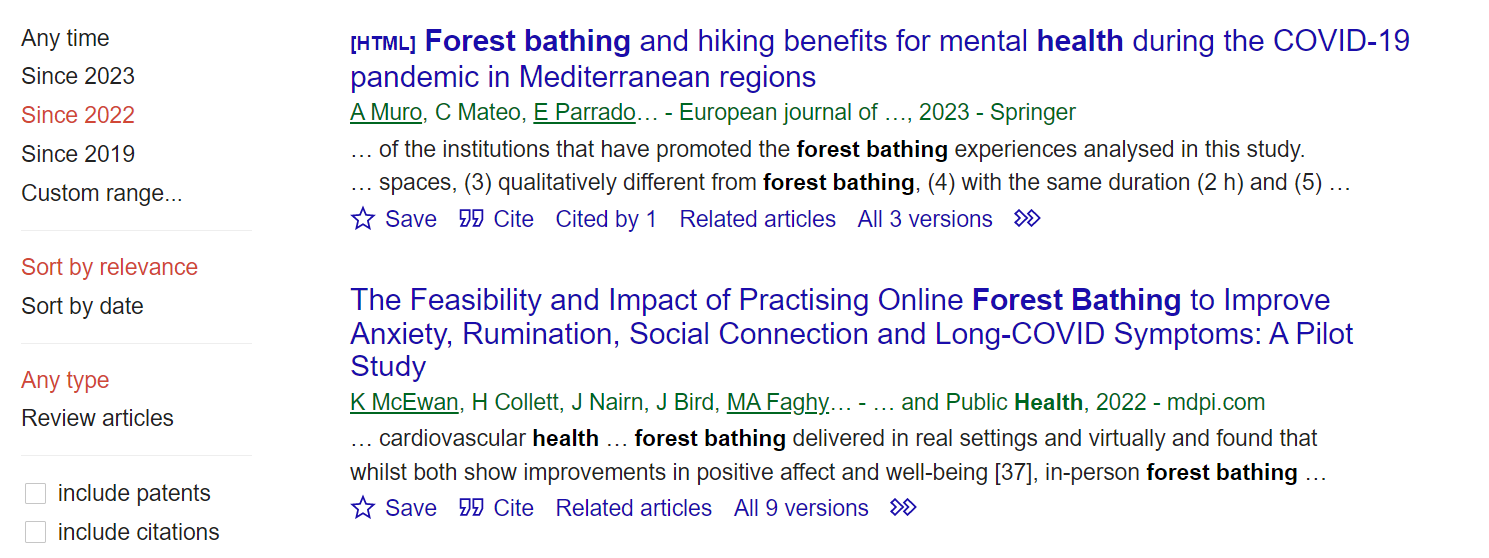

To refine your search even further, Google Scholar has filters you can use to tweak your search. For example, if you are only interested in very recent material, you could filter so that only material published after 2021 is shown. This is useful if you want to access material published in a particular time range.

Figure 14 Results on Google Scholar when they are filtered by date rangeA screenshot showing the results of the search filtered to only include articles published since 2022. The filter 'since 2022’ is in red, showing it is the filter being used

Figure 14 Results on Google Scholar when they are filtered by date rangeA screenshot showing the results of the search filtered to only include articles published since 2022. The filter 'since 2022’ is in red, showing it is the filter being used

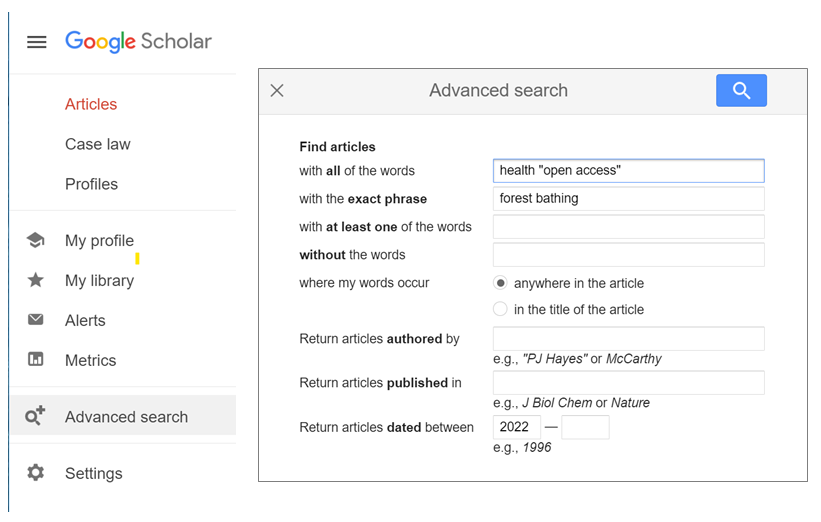

Most search engines or search facilities on repositories, collections or websites have an advanced search function that allows you to refine your search to cut down the number of results to something more useful. You can search for material published before or since a specific date, include or exclude specific words, or look for articles by a specific author.

To access advanced search

on Google Scholar, click on the menu hamburger in the top left.

Figure 15 The advanced search box on Google ScholarA screenshot showing the advanced search box on Google Scholar. This allows you to refine the search to include or exclude specific words, look for articles by specific authors or refine the date range.

Figure 15 The advanced search box on Google ScholarA screenshot showing the advanced search box on Google Scholar. This allows you to refine the search to include or exclude specific words, look for articles by specific authors or refine the date range.

What is the right number of resources to include in your EPQ research?

It’s difficult to give an exact number of resources you should aim to use in your EPQ research. You could keep going for ever – new articles come from researchers in a constant stream! A rule of thumb is to stop reading when you sense you are no longer finding new ideas.

Credibility.

Even a refined search is likely to throw up lots of material from a range of sources. Wherever your material comes from, you should always scrutinise it carefully. But how do you decide what you can trust (therefore making it useful), and what you can’t?

Assessing a source’s credibility is a good place to start. Making sure you draw your evidence from credible, believable, trustworthy sources is very important for your research.

Quiz: judging credibility.

Judging credibility – Thomas’ thoughts.

Thomas, who is a lecturer in space governance, discusses the credibility of materials. As you watch his video, listen out for the ways in which he judges credibility.

Judging credibility – Charlotte's thoughts.

Charlotte, who is a researcher in geochemistry, also has some thoughts about how she judges credibility.

Figure 16 Charlotte, a researcher in geochemistryA photograph of Charlotte

Figure 16 Charlotte, a researcher in geochemistryA photograph of Charlotte

If the source is in her field (in other words, she knows something about it), she looks in academic journals where she knows the work has been reviewed by experts (or ‘peer-reviewed’). She checks that:- the data support the conclusion the authors have come to

- the methods are appropriate and up-to-date

- they haven’t cherry-picked the best data and ignored others

- the authors don’t have any financial interest in coming to a particular conclusion.

If it’s an area she’s less familiar with, she starts with newspapers, online news and experts. She looks for:

- links to the original research

- what qualifies the writer to be an expert in that area

- whether other experts agree with the author

- any hint of conspiracy theories

- whether the authors have any financial interest in a particular conclusion.

What are the similarities and differences between how Charlotte and Thomas judge credibility? Charlotte is a science researcher, whereas Thomas is a law researcher – do you think this affects their processes?

Thomas and Charlotte both:

-

look at where the article has come from – a reputable source or one where work is reviewed by experts

-

consider the writer’s qualifications to be an expert on a subject

-

review whether other experts or sources agree with the writer

- check that the arguments or conclusions are supported by data.

Charlotte will look for links to the original research and any evidence of financial interests.

Thomas will look at the quality of the writing and the structure of the article.

Whether you use PROMPT, RAVEN or another method of assessing credibility, this will help you determine that you have the best sources possible for your project. Then it is time to get started reading for the literature review.

A good research review is more than just a list of ‘she says

this ... they say that … he says the other’. It’s an opportunity to test and

show the strength of different arguments and the contribution they have made to

your thinking.

The key is to critically read the material you have found.

The aim of critical reading is to assess the strength of the evidence and the argument. It is just as useful to conclude that a study, or an article, presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument as it is to identify the studies or articles that are weak.

As you read, it is useful to keep asking yourself questions such as:

Why am I reading this? – Because it’s interesting? Useful? Has good information for me?

Do I trust the source? – What evidence do I have that the source is trustworthy?

What claims are the authors making? – Have they included their conclusions?

Do I think those claims are trustworthy? – Have the authors given me the evidence they are basing their claims on so I can judge for myself?

Imagine you were researching the question: ‘what is the influence of advertising on people’s

consumption of junk food?’

Remembering that you will find material from a range of sources. Here we’ll use an article from the Guardian newspaper’s website.

Figure 17 Guardian articleA screenshot of an article from the Guardian newspaper’s online edition. The title of the article is ‘TfL junk food ban has helped Londoners shop more healthily – study’. The article is illustrated with a photograph of six hamburgers sitting on top of a large pile of chips.

Figure 17 Guardian articleA screenshot of an article from the Guardian newspaper’s online edition. The title of the article is ‘TfL junk food ban has helped Londoners shop more healthily – study’. The article is illustrated with a photograph of six hamburgers sitting on top of a large pile of chips.

What information in the article do you think would be relevant or useful to help you answer this question? Use the questions in the ‘Reading critically’ tab to help you reflect.

What did you think about as you read the article?

You might have picked up points such as:

Why am I reading this?

- It is about the effect of advertising on people buying junk food, so it is relevant to the question.

Do I trust the source?

- It comes from the Guardian, a well-known UK newspaper.

- The writer is named, so you could check on other things they have written – for example, if they specialise in writing articles about food or have a background in food science.

What claims are the authors making?

- That a ban on junk food advertising has led to a reduction in purchasing of unhealthy food.

Do I think those claims are trustworthy?

- The article mentions that the research was done by researchers at a university – you could look for them on the university website.

- One of the researchers is named and there is a quote from them.

At this stage, no one expects you to come up with all these possibilities! But keep those critical questions at the front of your mind as you search for and examine the evidence. Remember to ask:

- Why am I reading this?

- Do I trust the source?

- What claims are the authors making?

- Do I think those claims are trustworthy?

For more ideas on how to judge the credibility of the material you find and think critically about the contents, watch this short video on critical thinking, produced by the BBC and The Open University. It discusses five key strategies you can use to sharpen your critical thinking.

Summary.

In this article, we have looked at the second part of the research cycle – how to find the evidence that will help you answer your research question, and how you can start to read it critically and analyse its relevance to your question. When you have finished searching, reading and analysing, you are ready to move on to the next step: writing your dissertation.

This article is part of our ‘EPQ - help and tips’ series. Click here to view the other articles or find them listed below.

This article is part of our ‘EPQ - help and tips’ series. Click here to view the other articles or find them listed below.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews