Apocalyptic demography?

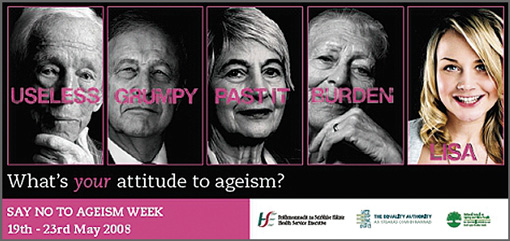

The article you just read could be seen as an example of what some gerontologists have termed ‘apocalyptic demography’ – that is, treating people living longer solely as a problem and burden to societies with terrible long term effects (Bytheway and Johnson, 2010). Rather than celebrating the fact that many people are living longer, and recognising the benefits that having more older people in the population might bring, apocalyptic demography focuses only on the negatives. An ageing population undoubtedly changes society and creates new challenges but it is both over-simplistic and ageist to frame this only as a problem. You may remember that part of Butler’s original definition of ageism was that it involved ‘systematic stereotyping’. As one commentator says:

The apocalyptic picture of the future is indeed ageist, because it objectifies people who are ageing and treats them as though they are all alike. They are not people anymore; they are ‘the burden’. From this negative point of view, these older people are not capable of contributing creative solutions to meeting their own needs. They have no agency. They are inert, the burden. The sky is falling, and it is falling because there are too many older people. That sounds ageist to me.

(Longino, 2005, p. 79)

One of the ways ‘isms’ like racism, sexism and, here, ageism, work is by over-generalising and stereotyping, as if everyone who can be categorised in a particular way is the same as everyone else in that category. Laslett’s concept of the Third Age can help to resist apocalyptic demography by making it clear that ageing is not simply about decline, dependency and difficulty.

Laslett’s argument about the growth of the Third Age is an example of an academic theory. Theories take a complex social phenomenon (in this case, ageing) and attempt to understand it more clearly by carrying out research and by developing explanations, categories and concepts. Theories can make things look simpler and more tidy than they actually are. Reality is usually messy and very complex, so no theory is perfect and explains everything. However, a useful theory takes you beyond what you already think you know and helps you to see things that you otherwise might not. That is why developing and refining theories is a key part of academic work.

One of the ways in which theories are developed is by other people reading and responding to the original theory. Laslett’s theory of the growth of the Third Age has been very influential and many people have developed and also criticised his ideas. While there is broad agreement that more people are living longer, healthier lives, some gerontologists have argued that Laslett’s emphasis on self-fulfilment in later life is unhelpful because it puts too much emphasis on personal achievement (Gilleard and Higgs, 2002). This can make it seem that, if people do not experience a Third Age, it is somehow their fault when, actually, their socio-economic circumstances or a combination of unlucky events are the main cause. Another common criticism is that the idea of the Third and Fourth Ages is rather unhelpful when thinking about people who are more dependent and frail. It is this issue that the next section focuses on.