The climate and ecological crisis: an uncomfortable truth

The climate and ecological crisis is with us. Global temperature rise is undisputed, the arctic sea ice is melting, and we are seeing more extreme weather in the form of storms, drought, fires and floods. We are witnessing the sixth mass extinction in the planet’s history with approximately half of all plant and animal species at risk (WWF, 2018). UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) ‘a code red for humanity’ (United Nations, 2021).

Hearing and reading about these facts can be deeply disturbing. Depth psychology tells us that when a thought or an experience is too painful or difficult to bear, we use psychological defences so we can carry on as if it wasn’t there. We can know and not know about the climate crisis at the same time, something known in psychoanalysis as disavowal. For instance, we can engage in wishful thinking (e.g. ‘technology/science will save us’), we can detach ourselves from the problem (e.g. ‘there’s nothing I can do about it’), we can blame others (e.g. ‘others that produce more pollution than me are the problem’) or we can immerse ourselves in the busyness of our everyday lives and not think about it.

Additionally, there are sociocultural defences which help to shield us from the impact of these facts. Have you noticed how difficult it is talk about the climate crisis in social situations? What we notice, pay attention to, and speak about in different contexts is socially constructed through rules. In his book, ‘The Elephant in the Room’, Eviatar Zerubavel (2006) describes the way in which certain subjects like climate change are avoided or considered taboo. These internalised social rules make it easier for us to ignore the topic of climate change to avoid feeling pain, fear or shame.

Although defences are useful to ensure we don’t become overwhelmed and unable to function, they can also stop us from engaging with the climate and ecological crisis. But what happens when these defences no longer hold back the reality? This is when we can experience eco-anxiety.

What is eco-anxiety?

Eco-anxiety is increasingly common, the term is even used by popular media, but what does it mean? There are various definitions:

· a chronic fear of environmental doom (Clayton et al., 2017)

· dread associated with negative environmental information more generally (Clayton, 2020)

· heightened psychological (mental, emotional, somatic) distress in response to the climate emergency (Bednarek, 2019).

The term is an oversimplification though and symptoms can be varied and mixed. As well as general anxiety people might experience depression, guilt, insomnia, panic attacks, shock, fear about the future, grief, helplessness and even a sense of numbness. Here are two personal accounts of eco-anxiety from people interviewed for The Guardian newspaper (Sarner, 2022):

· ‘My heart was pounding. My chest felt tight every time I thought about it – and I couldn’t not think about it. I’d often burst into tears because it felt overwhelming. It’s like a pit in your stomach – you feel weirdly empty. It’s not always the same, but it sometimes takes the form of feeling very sad, hopeless and alone.’

· ‘intense pressure, guilt, shame and anxiety to produce less and do everything to make up for what others were not doing’

The other problem with the term eco-anxiety is that it suggests a pathology or illness rather than what many climate psychologists and therapists now see as an appropriate response to the real threat of the climate crisis. The term also risks making the problem about the individual rather than acknowledging government and corporate responsibility.

What can we do to manage our feelings about the climate and ecological crisis?

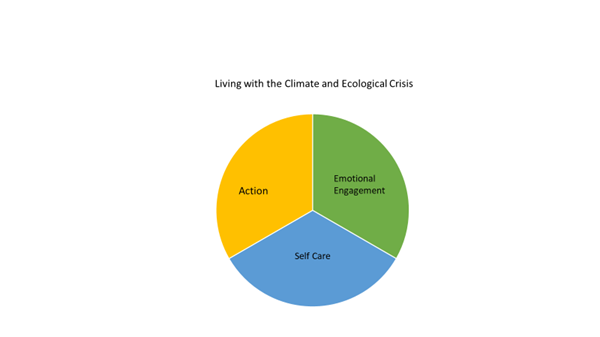

So, how can we be engaged with the climate and ecological crisis without eco-anxiety overwhelming us? The current literature suggests that three elements need to be present and in balance:

Three elements of living with the Climate and Ecological Crisis. Adapted from Pihkala, P. (2022) ‘The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal’, Sustainability, 14(24), p. 16628. doi:10.3390/su142416628

Three elements of living with the Climate and Ecological Crisis. Adapted from Pihkala, P. (2022) ‘The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal’, Sustainability, 14(24), p. 16628. doi:10.3390/su142416628

1. Emotional engagement

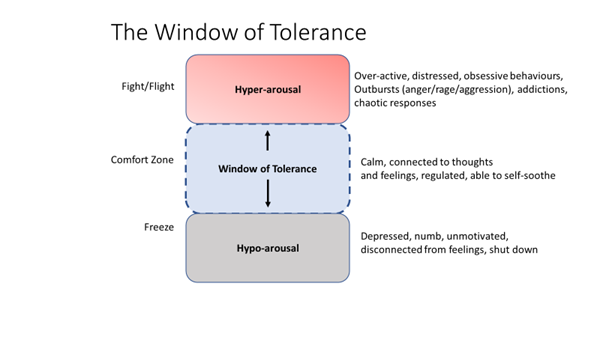

Acknowledging and processing difficult emotions is an important element in coping with the crisis. One useful concept that helps us to manage potentially overwhelming emotions is to think about our individual window of tolerance (Siegel, 1999).

The idea is that we each have a window of tolerance - the amount of stress that we can tolerate and still stay present and connected to our thoughts and feelings. We all have a threshold. When we experience more stress than we can tolerate, we become either hyper-aroused - commonly known as the fight/flight response – or we can become hypo-aroused with the so-called freeze response. When hyper-aroused, we can feel anxious or angry becoming impulsive, or engaging in addictive behaviours. When hypo-aroused, we can feel numb, disconnected and depressed.

We need to notice what’s happening within ourselves. Are we feeling anxious or irritable? Or are we feeling flat or even numb? We can then do things which are calming and soothing to bring us back within our window of tolerance.

Engaging with your emotions isn’t always easy and it’s important to speak to others who take your concerns seriously and make you feel it’s OK to talk about it. It is not helpful, for instance, to try to argue with someone who is in a state of denial. If that someone is a family member or friend, it can be particularly difficult. It may be better to avoid the subject rather than try to convince them of the reality of the climate crisis. You could speak to a climate aware therapist about your feelings to process them in a safe and supportive environment.

Finding groups in your own community is especially valuable, because practical local solutions can arise that help with feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness. For example, working on improving green spaces together, or campaigning for bike lanes. Being part of a group gives a sense of togetherness and belonging and creates social bonds which help us to feel supported as we manage our feelings.

2. Taking Action

Activism can help with feelings of eco-anxiety. This young activist sums up how activism has helped her:

‘I’m involved in activism because it gives you a real sense of power, it feels like you are actually doing something that will help. It’s so easy to feel powerless and overwhelmed by the many problems the world is facing and activism is a kind of a relief for that’ (in Godden et al., 2021).

Taking action is a form of problem solving and helps with feelings of powerlessness, leading to a sense of purpose or meaning, improving life satisfaction and increasing hopefulness. These positive emotions can help us to bear the distress we feel when we think about the climate crisis. Being part of a group gives a sense of togetherness and belonging, creating social bonds which help us to feel supported as we manage our feelings.

It is important that we do not confuse ‘taking action’ with ‘activism’ though. Taking action need not necessarily mean joining movements such as Extinction Rebellion. It has been shown that engaging in individual pro-environmental behaviours, such as cycling rather than driving, or buying fewer clothes, can benefit mental wellbeing as well as benefitting the environment.

3. Self-care

Taking care of yourself physically, emotionally, and spiritually is an important part of living with the climate crisis. Restorative practices such as time with family and friends, taking holidays and time off, getting enough sleep or practicing meditation or yoga are all important activities to build into your life.

Communities of care

Activist Charlie Hertzog Young says the most important support we need once we awaken to the reality of the climate crisis is to find communities of care:

‘what appears over and over again as a foundation for collective wellbeing and resilience is a dense, mutually supportive web of relationships – just like any thriving ecosystem’. (Gen Dread, 2023)

These could be close family and friends, neighbourhoods, formal and informal support groups, and networks of like-minded people.

Distancing

Sometimes, you will need respite from engaging with the reality of the climate crisis and the difficult emotions it can evoke. This kind of distancing, when done consciously, is different from the more unconscious states of disavowal.

Spending time in nature

This is a great stress reliever. If you don’t have access to natural environments outside, what can you do to bring nature indoors – plants, flowers, pictures? Even watching documentaries for instance can help us to feel connected. Remember the window of tolerance and the importance of soothing to keep us present, connected, and resilient.

Think about what you love about your life

This involves developing what psychologists call ‘meaning-focused coping’ (Ojala, 2016), which can include thinking about what you appreciate in your life, engaging and enjoying activities that are meaningful, or finding new relationships. It is about grounding ourselves in the present. Being grounded in the present helps us stay in our window of tolerance, while also keeping an eye on the future and discovering what matters most to us.,

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews