Incredible performances like this continue to remind us that women can perform far beyond any limits that were originally bestowed upon them by that 1928 committee. As women continue to pursue peak performance, whether that be in sport and exercise

or beyond, we have to think differently about what it takes to allow them to fulfil their potential, because it won’t always be the same things that have worked for the men.

Incredible performances like this continue to remind us that women can perform far beyond any limits that were originally bestowed upon them by that 1928 committee. As women continue to pursue peak performance, whether that be in sport and exercise

or beyond, we have to think differently about what it takes to allow them to fulfil their potential, because it won’t always be the same things that have worked for the men.

In the same weekend that Brigid Kosgei broke the women’s marathon record, Eliud Kipchoge performed a feat some never thought possible as he broke the 2-hour barrier for running a marathon. To achieve this Kipchoge had been part of the ‘Breaking-2’ project developed by Nike. Years in the making, the project scrutinised every aspect of human performance to make the fastest marathon in history possible. The Breaking-2 team scoured the world for the place with the best climate for endurance running – not too hot, not too cold, not too humid. They found a route with the best surface for running at speed. Nike designed shoes that improve running efficiency by 4%. On the day there were 42 pacers (all phenomenal runners in their own right) who took turns to run, at the exact pace required to break 2 hours, in a specific formation that provided Kipchoge the best ‘slipstream’ which also saved him energy. A lead car shone a laser onto the road to pinpoint the shortest route, ensuring Kipchoge didn’t run a step too far. A cyclist rode alongside him to pass specially formulated sports drink to ensure he didn’t become depleted of energy or dehydrated. And that’s only some of the science that supported this incredible feat.

The ‘default male’ in sports science research

At the moment, in sport, female athletes usually train and are coached in a similar way to their male counterparts. The support that is applied to their performance (nutrition, physiology, psychology, etc.) is usually based on research that’s

been done on men, or what has seen to been successful with male athletes. Very little research, in fact, examines determinants of sports performance or effectiveness of interventions in women. Of all the papers in the top three sports science

and medicine journals for a one-year period, only 4% of the research was done exclusively on women.

At the moment, in sport, female athletes usually train and are coached in a similar way to their male counterparts. The support that is applied to their performance (nutrition, physiology, psychology, etc.) is usually based on research that’s

been done on men, or what has seen to been successful with male athletes. Very little research, in fact, examines determinants of sports performance or effectiveness of interventions in women. Of all the papers in the top three sports science

and medicine journals for a one-year period, only 4% of the research was done exclusively on women.

Alongside this lack of research is poor methodological quality of existing research, which further compounds our ability to draw conclusions or recommendations on what is best for female athletes from what evidence does exist. This gender gap in the science of sports performance, which was discussed recently by Brittany Mitchell of ESPN and Dr Clare Minihan of Griffiths University in this article, means we make lots of assumptions that our preparation of women athletes is optimal. In turn this means there are often lots of unexploited opportunities for females looking to really optimise training and performance that we don’t consider.

What if Kipchoge had been female?

Let’s imagine Eliud Kipchoge had been a female athlete and we wanted to leave no stone unturned in ensuring ‘she’ produced the peak performance on ‘Breaking-2’ race day. Alongside all the things that were done to support Kipchoge for his sub-2 hour marathon, what are some of the other, female-specific opportunities for our athlete?

The impact of the menstrual cycle needs to be fully understood

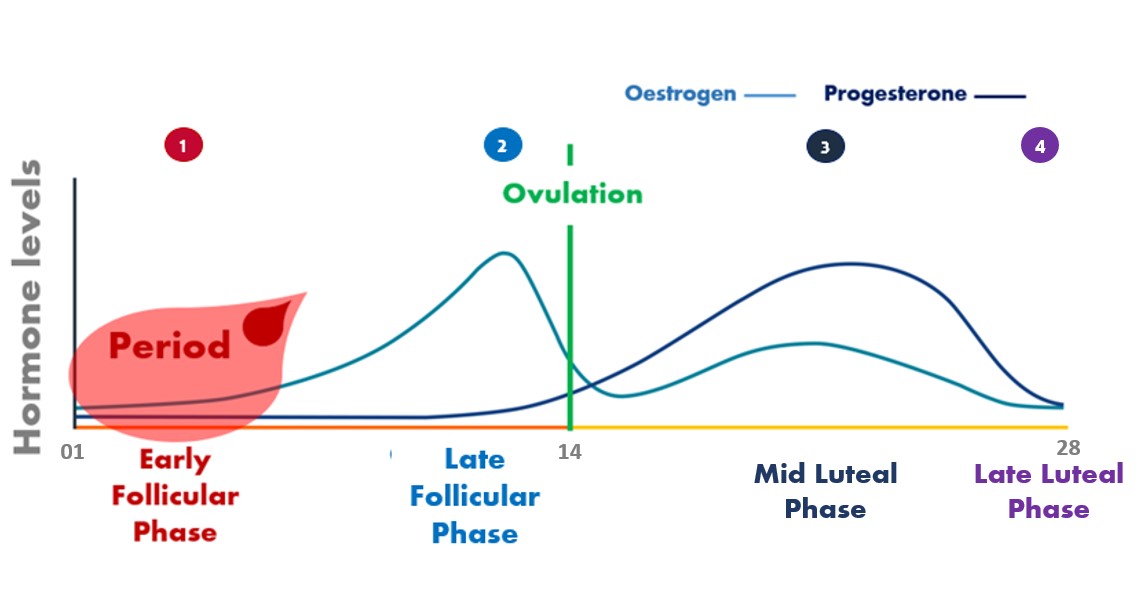

Let’s start with the menstrual cycle. The cycle is typically defined by two ‘halfs’, the first is the follicular phase and the second the luteal phase. However, in terms of how the hormones of the cycle might influence how an athlete feels physically and emotionally, the menstrual cycle can be divided into four distinct stages with each having significantly different hormonal profiles:

- The start of the cycle is known as the early follicular phase, when oestrogen and progesterone, the two main hormones of the cycle, are both low. The first day of the cycle is the first day of bleeding (known as the period or menstruation).

- The late follicular phase precedes ovulation (which usually occurs around the middle of the cycle) and is when oestrogen peaks but progesterone remains low.

- During the mid-luteal phase (around days 20-22) both oestrogen and progesterone levels are high.

- In the late luteal phase, if the egg released from the ovaries has not been fertilised, both progesterone and oestrogen levels drop. This time is often referred to as ‘pre menstrual’, as it occurs at the end of one cycle, and just before the start of the next cycles menstruation.

These four stages of the menstrual cycle are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 A typical menstrual cycle, showing fluctuations of oestrogen and progesterone, and four distinct stages where hormone levels, and/or ratio of oestrogen and progesterone are distinctly different. It's worth noting that although 28 days is a typical cycle length, only 13% of women actually have a 28 day cycle, and a healthy cycle length can range from 21-35 days, and up to 40 days adolescents. Ovulation doesn't always occur exactly half way through the cycle, for example a woman with a 35 day cycle might have a 23 day follicular phase ending in ovulation, followed by a 12 day luteal phase.

Figure 1 A typical menstrual cycle, showing fluctuations of oestrogen and progesterone, and four distinct stages where hormone levels, and/or ratio of oestrogen and progesterone are distinctly different. It's worth noting that although 28 days is a typical cycle length, only 13% of women actually have a 28 day cycle, and a healthy cycle length can range from 21-35 days, and up to 40 days adolescents. Ovulation doesn't always occur exactly half way through the cycle, for example a woman with a 35 day cycle might have a 23 day follicular phase ending in ovulation, followed by a 12 day luteal phase.

So, the first thing we would do with our marathon runner is track her cycle and monitor physical and emotional feelings across a number of months. Is there a time she feels more energised or a time when she feels more fatigued? Oestrogen is a feel-good hormone. It increases levels of serotonin, which can improve confidence, motivation and mood. There’s no doubt these effects will come in handy when you are trying to break the limits of human endurance. There is also a protective function of oestrogen in exercise induced muscle damage, so through monitoring we might find that our athlete recovers more quickly from a certain training session in the late follicular phase. Progesterone can influence the onset and quality of sleep, and our athlete might notice that she sleeps better in the mid luteal phase of her cycle.

The hormones of the cycle also affect how your body uses fuel when you exercise. Research has shown that in the mid luteal phase high oestrogen and progesterone can have a glycogen sparing effect during endurance exercise – where muscles store more glycogen and fat is used more readily for energy. This knowledge might influence how the athlete fuels before and during training and racing, or when we schedule different types of training sessions.

Oestrogen is a feel-good hormone. It increases levels of serotonin, which can improve confidence, motivation and mood.

Tracking of the menstrual cycle will also ensure that we record the athlete’s menstruation. Having a period is a vital sign of health and in athletes it is a great indication that they are getting their fuelling right. If a female athlete doesn’t balance her training load with her nutritional intake then, over time, her body will shut down her menstrual cycle: the body will prioritise other physiological systems over and above getting pregnant (which is what the menstrual cycle is for!).

Suppressing the important hormones of the menstrual cycle can have significant short- and long-term health and performance impact. This condition, known as Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, can occur in both males and females, but in women the presence of a period is a great indicator that our athlete is fuelling her training well. It is important to note that whilst we have some evidence to suggest what might be happening with our athlete’s hormones and their effect on her training and performance, every woman experiences her cycle differently (physically and emotionally). Getting to know the individual athlete, and how she feels across her whole cycle, in the context of her life and her sport is vital. We have to tune into what opportunities her cycle offers her as an athlete and also what challenges it poses. The goal would be to manage any cycle symptoms so they don’t impair training quality or performance and capitalise on days when the cycle can help optimise training and recovery.

Having the right sports bra is so important

As well as understanding the athlete’s menstrual cycle, we would also work to optimise her breast support. A poorly fitting sports bra can cost energy, as muscles works harder to counter the movement of the breasts during each stride. If you have too much breast bounce it also affects your stride length, shortening it so you don’t cover as much distance with each step. Meanwhile, if the under band is too tight it can restrict the rib cage, using more energy to fill the lungs on each breath. All of these effects combine so that if an individual lined up on the start line of a marathon against their clone and the only things different about them was that the clone was wearing a poor fitting bra and the individual a great fitting bra, the clone would finish a mile behind!

We also need to consider the pelvic floor

What if our hypothetical ‘Breaking 2’ female athlete was also one of the 40% of female athletes who do high impact sports who suffers with stress incontinence due to poor pelvic floor function? Aside from causing embarrassment and anxiety, dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscle – which causes the poor bladder control – can result in the athlete modifying her technique and may increase her injury risk.

40% of female athletes... suffer with stress incontinence due to poor pelvic floor function.

The cause for urinary incontinence in female athletes is still unclear. It could be related to the significant and sudden intra-abdominal pressure increases, especially during high-impact activities such as running and jumping, or may be due to female athletes having very strong pelvic floor muscles from continued training of the abdominal muscle or repeated activation of the pelvic floor muscle, which can cause fatigue and weaken it.

Importantly, urinary incontinence in female athletes is seriously underreported and, as a result, undertreated. We must not normalise incontinence as ‘just a part of doing sport’ but work to encourage athletes to seek advice and support if they are experiencing urine leakage at any time. Women’s health physiotherapists are experienced at identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction, and we would certainly have one as part of our support team for this ‘Breaking 2’ female athlete!

When we are supporting athletes trying to fulfil their potential, if we explore the important factors that could be challenges or opportunities for females specifically, I think we have some fantastic unexploited areas where women can make both significant and marginal gains in performance. And if we step back and think more broadly than those athletes who are chasing world records and human limits, it seems possible that even us mere mortals who are just trying to be the best version of ourselves could also use this science – and understanding of ourselves – to help us achieve great things too.

Explore more articles in this collection of Women in sport.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews