2.3 Gender and detective fiction

The inter-war years saw the expansion of a female readership across social classes, partly as rise in literacy fostered by the education reforms of the late nineteenth century, but it also saw, for the first time, reading habits reflect the opening of new professional horizons, traditionally thought of as male, on account of the mass mobilisation of the war effort (for a good summary of this within the broader context, see McAleer, 1992, pp. 53–4).

Detection was one such potential horizon, and the demand for detective stories from female readers was particularly strong. Rzepka has noted that the ‘prominence of the New Woman’ as well as the popularity of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories led to a massive increase in female readership for detective fiction and wonders at the lag in demand to see women in the central role of the detective protagonist (Rzepka, 2005, pp. 149, 158). America, which had not lost its young men in the same horrific numbers in the First World War, saw instead the rise in popularity of its homegrown detective for the age – the hardboiled private eye in the growing industry of pulp fiction. If the likes of Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon) or Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe (The Big Sleep) share some of the physical prowess of Sherlock Holmes, their methods, moral frameworks, and social status in many ways make them the antithesis of earlier models of the investigating sleuth.

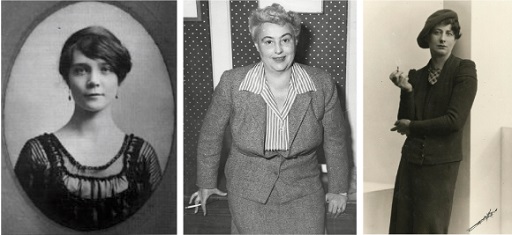

One obvious advance into the territory of detective fiction, however, was the success of women authors in the post-war period. Alongside important male contemporaries – particularly G. K. Chesterton (the Father Brown stories) and Nicholas Blake (the Nigel Strangeways series) – the golden age of detective fiction was defined in many ways by the work of four women, dubbed the ‘Queens of Crime’: Margery Allingham (1904–1966), Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), Ngaio Marsh (1895–1982) and, of course, Christie herself. All provided important contributions to the genre and helped to carry the private detective archetype beyond the dominant figure of Holmes. Sayers, for example, introduced Lord Peter Wimsey, an aristocratic amateur sleuth with enormous personal wealth, breaking the bohemian mould. Allingham had her version too in the shape of Albert Campion. Christie emerged as supreme among these writers and would remain a dominant force in the genre for decades, propelled initially by the success of her own iteration of the European detective: Hercule Poirot.

Poirot is an example of what has traditionally been identified as a ‘feminised’ version of the analytical detective type. Susan Rowland (2010, p. 121) challenges this conceptualisation somewhat. His ‘feminine’ or ‘domesticated’ qualities are on show in Roger Ackroyd and turn out to be crucial to the solution of the crime, including, for example, his interest in the arrangement of furniture in the room where the murder took place and his ability to identify an apron fragment. These qualities, in fact, to some extent laid the groundwork for another wildly popular take on the figure of the detective: that of Miss Jane Marple, who would later feature in 12 of Christie’s novels.