The emergence of modern art in Paris

Let’s take a step back to the middle of the nineteenth century and consider the emergence of modern art in Paris. The new art that developed with Gustave Courbet (1819–77), Manet and the Impressionists entailed a self-conscious break with the art of the past. These modern artists took seriously the representation of their own time. In place of allegorical figures in togas or scenes from the Bible, modern artists concerned themselves with the things around them. When asked to include angels in a painting for a church, Courbet is said to have replied ‘I have never seen angels. Show me an angel and I will paint one.’ But these artists were not just empirical recording devices. The formal or technical means employed in modern art are jarring and unsettling, and this has to be a fundamental part of the story. A tension between the means and the topics depicted, between surface and subject, is central to what this art was. Nevertheless, we miss something crucial if we do not attend to the artists’ choices of subjects. Principally, these artists sought the signs of change and novelty – multiple details and scenarios that made up contemporary life. This meant they paid a great deal of attention to the new visual culture associated with commercialised leisure.

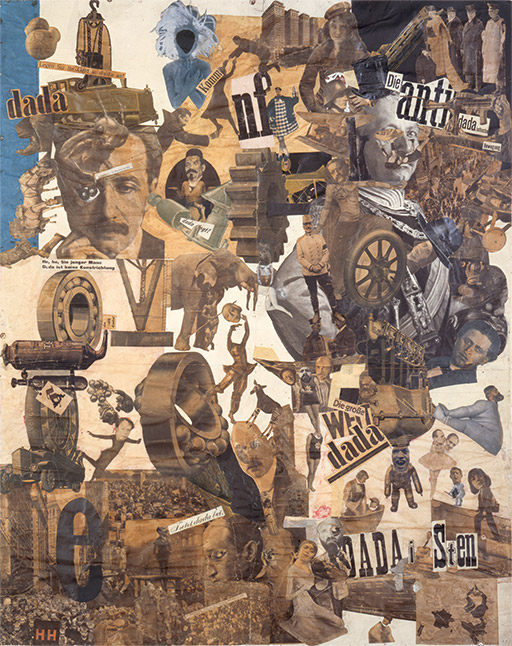

Greenberg contrasted the mainstream of modern art, concerned with autonomous aesthetic experience and formal innovation, with what he called ‘dead ends’ – directions in art that he felt led nowhere. Even when restricted to the European tradition, this marginalised much of the most significant art made in interwar Europe – Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism (Greenberg, 1961). The groups of artists producing this art – usually referred to collectively as the ‘avant-garde’ or the ‘historical avant-garde’ – wanted to fuse art and life, and often based their practice on a socialist rejection of bourgeois culture (see, in particular, Bürger, 1984). From their position in western Europe, the Dadaists mounted an assault on the irrationalism and violence of militarism and the repressive character of capitalist culture; in collages, montages, assemblages and performances, they created visual juxtapositions aimed at shocking the middle-class audience and intended to reveal connections hidden behind everyday appearances (see Figure 23). The material for this was drawn from mass-circulation magazines, newspapers and other printed ephemera. The Constructivists participated in the process of building a new society in the USSR, turning to the creation of utilitarian objects (or, at least, prototypes for them). The Surrealists combined ideas from psychoanalysis and Marxism in an attempt to unleash those forces repressed by mainstream society; the dream imagery is most familiar, but experiments with found objects and collage were also prominent. These avant-garde groups tried to produce more than refined aesthetic experiences for a restricted audience; they proffered their skills to help to change the world. In this work the cross-over to visual culture is evident; communication media and design played an important role. Avant-garde artists began to design book covers, posters, fabrics, clothing, interiors, monuments and other useful things. They also began to merge with journalism by producing photographs and undertaking layout work. In avant-garde circles, architects, photographers and artists mixed and exchanged ideas. For those committed to autonomy of art, this kind of activity constitutes a denial of the shaping conditions of art and betrayal of art for propaganda, but the avant-garde were attempting something else – they sought a new social role for art. One way to explore this debate is by switching from painting and sculpture to architecture and design.