The Phoenicians were an ancient civilization that emerged in 1800 B.C. in the northern Levant and by 800 B.C. had spread their culture across the Mediterranean to parts of Asia, Europe and Africa through trade networks and settlements. Despite their widespread influence, most of what we know about the Phoenicians comes from Greek and Egyptian documents on this civilization.

In a recent PLOS ONE study, researchers analyzed ancient DNA from Phoenician remains found in Sardinia and Lebanon to investigate how Phoenicians integrated with the Sardinian communities they settled. The authors looked at mitogenomes — DNA found in cells’ mitochondria, which is inherited from one’s mother — in a search for markers of Phoenician ancestry. They found 14 previously unknown ancient mitogenome sequences in pre-Phoenician (around 1800 B.C.) and Phoenician (around 700 to 400 B.C.) remains from Lebanon and Sardinia. Then, they compared these with 87 new complete mitogenomes from modern Lebanese people and 21 recently published pre-Phoenician ancient mitogenomes from Sardinia.

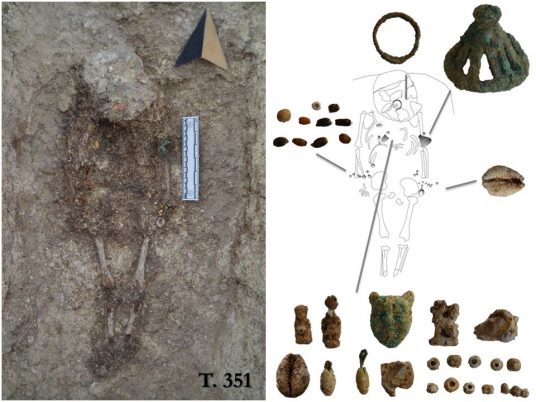

An archaeological site in Monte Sirai, Sardinia, consisting of a tomb with personal ornaments

An archaeological site in Monte Sirai, Sardinia, consisting of a tomb with personal ornaments

The genetic comparison showed evidence that some lineages of indigenous Sardinians continued after Phoenician settlement in Monte Sirai, Sardinia, which suggests that integration between Sardinians and Phoenicians occurred there. They also discovered evidence of new, unique mitochondrial lineages in Sardinia and Lebanon, which may indicate the movement of women from sites in the Middle East or North Africa to Sardinia and the movement of European women to Lebanon. Given their findings, the authors suggest that there was a degree of female mobility and genetic diversity in Phoenician communities, indicating that migration and cultural assimilation were common occurrences.

Study co-author Pierre Zalloua says, “This DNA evidence reflects the inclusive and multicultural nature of Phoenician society. They were never conquerors, they were explorers and traders.”

This article was originally published by PLOS One under a CC-BY licence

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews