Various characters in Tolstoy's epic novel War and Peace have sudden epiphanies relating to the banality of their existence. Early on, Prince Andre tries to find his purpose by going to war. However, after his near-death experience at Austerlitz, he sees the falsehood of his life though a spiritual vision. On the other hand, Pierre, whose marriage to conniving Helene acts as a catalyst for his philosophising, despises his artificial life. His involvement with Freemasonry gives him some meaning for a while but not for long. Tolstoy, through his own experiences and pondering, narrates the novel to show inadequacies when the characters try to find a meaning in their life, this is shown when Pierre rejects the Masons. It's only when Pierre discovers his true love that his life is finally given some meaning.

Various characters in Tolstoy's epic novel War and Peace have sudden epiphanies relating to the banality of their existence. Early on, Prince Andre tries to find his purpose by going to war. However, after his near-death experience at Austerlitz, he sees the falsehood of his life though a spiritual vision. On the other hand, Pierre, whose marriage to conniving Helene acts as a catalyst for his philosophising, despises his artificial life. His involvement with Freemasonry gives him some meaning for a while but not for long. Tolstoy, through his own experiences and pondering, narrates the novel to show inadequacies when the characters try to find a meaning in their life, this is shown when Pierre rejects the Masons. It's only when Pierre discovers his true love that his life is finally given some meaning.

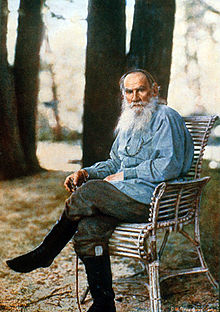

It's evident in the novel that the philosophical author thought about life and death a great deal. In his essay 'Death and the meaning of life' (below) Tolstoy's understanding of death took away all the purpose of life, so much so that Tolstoy began to devalue his existence and was worried he would want to take his own life.

Death and the Meaning of Life - by Leo Tolstoy

In my writings I advocated, what to me was the only truth, that it was necessary to live in such a way as to derive the greatest comfort for oneself and one’s family.

Thus I proceeded to live, but five years ago something very strange began to happen to me: I was overcome by minutes at first of perplexity and then of an arrest of life, as though I did not know how to live or what to do, and I lost myself and was dejected. But that passed, and I continued to live as before. Then those minutes of perplexity were repeated oftener and oftener, and always in one and the same form. Theses arrests of life found their expression in ever the same questions: ‘Why? Well, and then?’ […]

The questions seemed to be so foolish, simple, and childish. But the moment I touched them and tried to solve them, I became convinced, in the first place, that they were not childish and foolish, but very important and profound questions in life, and, in the second, that, no matter how much I might try, I should not be able to answer them. Before attending to my Samára estate, to my son’s education, or to the writing of a book. I ought to know why I should do that. So long as I did not know why, I could not do anything, I could not live. Amidst my thoughts of farming, which interested me very much during that time, there would suddenly pass through my head a question like this: ‘All right, you are going to have six thousand desyatinas of land in the Government of Samára, and three hundred horses, – and then?’ And I completely lost my senses and did not know what to think farther. Or, when I thought of the education of my children, I said to myself: ‘Why?’ Or, reflecting on the manner in which the masses might obtain their welfare, I suddenly said to myself: ‘What is that to me?’ Or, thinking of the fame which my works would get me, I said to myself: ‘All right, you will be more famous than Gógol, Pushkin, Shakespeare, Moliere, and all the writers in the world, – what of it?’ And I was absolutely unable to make any reply. The questions were not waiting, and I had to answer them at once; if I did not answer them, I could not live.

I felt that what I was standing on had given way, that I had no foundation to stand on, that which I lived by not longer existed, and that I had nothing to live by.

My life came to a standstill. I could breathe, eat, drink and sleep, and could not help breathing, eating, drinking and sleeping; but there was no life, because there were no desires the gratification of which I might find reasonable. If I wished for anything, I knew in advance that, whether I gratified my desire or not, nothing would come of it. If a fairy had come and had offered to carry out my wish, I should not have known what to say. If in moments of intoxication I had, not wishes, but habits of former desires, I knew in sober moments that was a deception, that there was nothing to wish for. I could not even wish to find out the truth, because I guess what it consisted in. The truth was that life was meaningless. It was as though I had just been living and walking along, and had come to an abyss, where I saw clearly that there was nothing ahead but perdition. And it was impossible to stop and go back, and impossible to shut my eyes, in order that I might not see that there was nothing ahead but suffering and imminent death, – complete annihilation.

What happened to me was that I, a healthy, happy man, felt that I could not go on living, – an insurmountable force drew me on to find release from life. I cannot say I wanted to kill myself.

The force which drew me away from life was stronger, fuller, more general than wishing. It was a force like the former striving after life, only in an inverse sense. I tended with all my strength away from life. The thought of suicide came as naturally to me as had come before the ideas of improving life. That thought was so seductive that I had to use cunning against myself, lest I should rashly execute it. I did not want to be in a hurry, because I wanted to use every effort to disentangle myself: if I should not succeed in disentangling myself, there would always be time for that.

At such times, I, a happy man, hid a rope from myself so that I should not hang myself on a cross-beam between two safes in my room, where I was by myself in the evening, while taking off my clothes, and did not go out hunting with a gun, in order not to be tempted by any easy way of doing away with myself. I did not know myself what it was I wanted: I was afraid of life, strove to get away from it, and, at the same time, expected something from it.

All that happened with me when I was on every side surrounded by what is considered to be complete happiness. I had a good, loving and beloved wife, good children and a large estate, which grew and increased without any labour on my part. I was respected by my neighbours and friends, more than ever before, was praised by strangers, and, without any self-deception, could consider my name famous. With all that, I was not deranged or mentally unsound, – on the contrary, I was in full command of my mental and physical powers, such as I had rarely met with in people of my age: physically I could work in a field, mowing, without falling behind a peasant; mentally I could work from eight to ten hours in succession, without experiencing any consequences from the strain. And while in such condition I arrived at the conclusion that I could not live, and, fearing death, I had to use cunning against myself, in order that I might not take my life. […]

The former deception of the pleasures of life […] no longer deceives me. No matter how much one should say to me, ‘You cannot understand the meaning of life, do not think, live!’ I am unable to do so, because I have been doing it too long before. Now I cannot help seeing day and night, which run and lead me up to death. I see that alone, because that alone is the truth. Everything else is a lie. […]

‘My family – ‘ I said to myself, ‘but my family, my wife and children, they are also human beings. They are precisely in the same condition that I am in: they must either live in the lie or see the terrible truth. Why should they live? Why should I love them, why guard, raise and watch them? Is it for the same despair which is in my, or for dullness of perception? Since I love them, I cannot conceal the truth from them, – every step of cognition leads them up to this truth. And the truth is death.’

‘Art, poetry?’ For a long time, under the influence of the success of human praise, I tried to persuade myself that that was a thing which could be done, even though death should come and destroy everything, my deeds, as well as my memory of them; but soon I came to see that that, too, was a deception. It was clear to me that art was an adornment of life’ a decoy of life. But life lost all its attractiveness for me. How, then, could I entrap others? So long as I did not live my own life, and a strange life bore me on its waves; so long as I did not live my own life, and a strange life bore me on its waves; so long as I believed that life had some sense, although I was not able to express it, – the reflections of life of every description in poetry and in the arts afforded me pleasure, and I was delighted to look at life through this little mirror of art; but when I began to look for the meaning of life, when I experienced the necessity of living myself, that little mirror became either useless, superfluous and ridiculous, or painful to me. […]

‘Well, I know’, I said to myself, ‘all which science wants so persistently to know, but there is no answer to the question about the meaning of my life.’ But in the speculative sphere I saw that, in spite of the fact that the aim of the knowledge was directed straight to the answer of my question, or because of that fact, there could be no other answer than what I was giving to myself: ‘What is the meaning of my life’ – ‘ None’ Or, ‘What will come of my life?’ – ‘Nothing.’ Or, ‘Why does everything which exits exist, and why do I exist?’ – ‘Because it exists.’ […]

Rational knowledge in the person of the learned and the wise denied the meaning of life, but the enormous masses of men, all humanity, recognized this meaning in an irrational knowledge. This irrational knowledge was faith, the same that I could not help but reject. That was God as one and three, the creation in six days, devils and angels, and all which I could not accept so long as I had not lost my senses.

My situation was a terrible one. I knew that I should not find anything on the path of rational knowledge but the negation of life, and there, in faith, nothing but the negation of reason, which was still more impossible than the negation of life. From the rational knowledge it followed that life was an evil and men knew it, – it depended on men whether they should cease living, and yet they lived and continued to live, and I myself live, though I had known long ago that life was meaningless and an evil. From faith it followed that, in order to understand life, I must renounce reason, for which alone a meaning was needed.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews