7.1 Decoding pictures

In this section, we use the ideas of scholars of children’s literature who have tried to look more systematically and in depth at the ways in which children’s books communicate with the reader visually as well as in words. One such scholar, William Moebius, wrote that ‘we can pour emotion and affection’ into the pages of children’s picturebooks and the lovable creatures which inhabit them, reliving a kind of second childhood, or we can choose to ‘watch more closely … and attend to elements of design and expression’ (1986, 142).

Moebius draws on, among others, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, a book widely analysed in the academic literature on picturebooks. Sendak gained critical acclaim for Where the Wild Things Are – a tale of a young boy, Max, who, having been sent to his room for his wild behaviour, embarks on a fantasy voyage to the land of the Wild Things, where he is made king. You can find out more about this book and see images from it in 10 wild facts about Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . Moebius, in this reading, looks at how images and text work together to create communicative meaning, breaking this down into different aspects of visual communication which he called codes. He identifies these, broadly, as falling into five categories, as shown in Table 1 below. Alongside each code, features which can vary are listed. These are expressed as questions that you can ask about any image.

| Code | |

|---|---|

| position and size | Is the subject positioned centrally or in the margins? How big or small are figures in relation to others, and to the image as a whole? Are figures on the left or right of the page? (Left = safe, secure, known, given; right = less secure, unknown, new, unexpected) |

| perspective | Are there horizons in the image or not? Is the image flat or does it have depth? What appears in the foreground, and what in the background? |

| framing | Are there boundaries around the whole image and/or around parts of it (for example strong horizontal or vertical lines ‘framing’ a figure)? Are images spilling or pushing outside their frames, or are they contained? |

| line | Are lines vertical and horizontal (stability), or on the diagonal (unsettling, dynamic, indicating movement or change)? Are lines sketchy (movement) or thick and intense (intensity, paralysis or stasis)? Are they smooth and parallel (indicating order) or jagged, angular (spelling trouble, danger, conflict)? Are there lots of lines and squiggles (energy, anxiety) or few (calm)? |

| colour | Are colours warm or cool? (Suggesting feelings, relationships) Bright or dark? (Suggesting feelings of fear or optimism, sadness or happiness) |

According to Moebius, these features have the potential to convey specific meanings, due to the cultural associations that they have, at least for Western readers. In the next activity you have the opportunity to try out this kind of analysis for yourself.

Activity 11

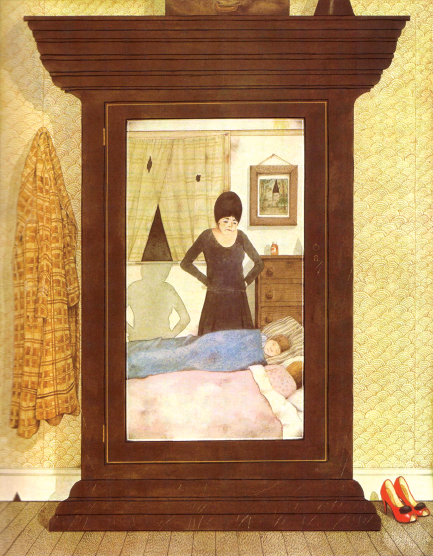

Study Figure 19 below; the text and the illustration are on two facing pages in Anthony Browne’s picturebook version of Hansel and Gretel (1981). As you observe details, make a note of the following:

- What details do you notice in terms of Moebius’s codes listed above?

- How might these details be significant for the story?

Don’t worry if you find some codes more difficult to identify than others.

At daybreak, before the sun had risen, the woman came and wakened the children. ‘Get up, you lazybones, we must go to the forest to fetch wood.’ She gave them each a small piece of bread, saying, ‘Here’s something for your dinner, but don’t have it too soon, for you’ll get nothing else.’ Gretel put the bread inside her coat, and Hansel put all the pebbles into his trouser pockets. Then they set out together for the forest.

Discussion

Position and size: Note the prominence of the wardrobe and its occupation at the centre of the image. Within the bold frame created by the wardrobe, the woman standing over the sleeping children is also central. The children are shown lower down on the page than the woman, and Moebius would see this as evidence of their lesser social status or lower degree of power.

Perspective: This image is quite complex in terms of perspective; there is no horizon per se, but there are horizontal lines, made by the wardrobe and by the windowsill and chest of drawers shown in the mirror. There is a window at the back, but the shape made by the almost-closed curtains (and the way that the woman’s shadow falls to meet this shape) hints at sinister developments to come (the shape of a black witch’s hat).

Framing: This is achieved quite clearly by the large, imposing wardrobe: Moebius says that rectangular shapes often indicate problems or encounters with discipline. The window provides another rectangle, and we know from the shadow and the black triangle formed by the curtains that this is unlikely to improve security for the children.

Line: Both verticals and horizontals are present, but also some unsettling diagonals and several triangular shapes.

Colour: This is clearly significant; not only is black used significantly in terms of foreshadowing the woman as ‘witch’, but the colours as a whole are muted and drab. What each colour means is to some extent a question for the viewer’s interpretation, but it seems reasonable to surmise that this is not a happy home.

You could also consider the following questions in relation to this image

- Why are the characters shown reflected in a mirror? (What do mirrors signify in fairy tales? There is no single answer, of course.)

- Why is a wardrobe shown?

- How might the image have been done differently? Perhaps you have another version of Hansel and Gretel at home, to compare?

- Does the transposition of the story into a modern setting disturb or delight you? Why?

The illustrator Martin Salisbury, whom you heard in Activity 8, has expressed scepticism about this kind of visual analysis of children’s picturebooks. He feels that academic interest in these images has been driven mainly by an interest in the educational role of children’s books, whereas he prefers to understand them as art. Rather than looking for non-visual ‘meanings’ behind the pictures, he comments that in many cases ‘very often, the meaning simply is the pictures’ (Interview with Martin Salisbury, 2009).

Having had an opportunity to try out this kind of analysis for yourself, what do you think?