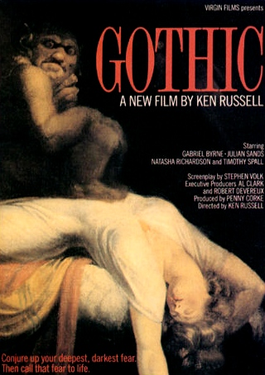

The poster for the film Gothic (1986 - Artwork created by Paul Dufficey)Ken Russell’s 1986 film Gothic (released by the BFI on Blu-ray) tells the story of the night on which two of the most famous archetypes of horror fiction were first imagined: Frankenstein’s monster, and the vampire-as-aristocrat. It’s the story of Romantic poets, Gothic novelists, phantasmagorical nightmares and sexual paranoia, all blended together in the intrigues that play out in a Baroque mansion on the shores of Lake Geneva in the early nineteenth century.

The poster for the film Gothic (1986 - Artwork created by Paul Dufficey)Ken Russell’s 1986 film Gothic (released by the BFI on Blu-ray) tells the story of the night on which two of the most famous archetypes of horror fiction were first imagined: Frankenstein’s monster, and the vampire-as-aristocrat. It’s the story of Romantic poets, Gothic novelists, phantasmagorical nightmares and sexual paranoia, all blended together in the intrigues that play out in a Baroque mansion on the shores of Lake Geneva in the early nineteenth century. The writer of the screenplay, Stephen Volk, has said that the film was his homage to the Hammer horror films of the 60s and 70s. In an interview with the journalist James Payne, director Ken Russell described it as ‘a pre-Raphaelite romp’. Both descriptions speak to the influence that this one evening from the summer of 1816 has had on the cultural imagination over the last two centuries. The historical event around which the plot of the film is woven is the real-life origin story for the horror genre that Hammer Films later helped re-define; while the Pre-Raphaelite movement had both literal and figurative forebears amongst those present on that auspicious evening.

But the event itself, as well as the novels it gave rise to, is also bound up with radical politics and with rebellious acts of belief and behaviour which presaged many of the values around personal liberty and social equality that we hold dear today. The cast of assembled characters – Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, Mary’s step-sister Claire Clairmont, and Byron’s personal physician John Polidori – were living embodiments of the liberal ideals that were causing such an affront to the conservative and patrician values of the ruling classes in the early nineteenth century.

So how, if at all, does Gothic engage with this side of the story? Russell’s primary interest is very much in the proto-horror potential of the foundations of the Frankenstein myth. But is there room also for politics in amongst his sinister concoction? Or has the radical philosophy that was so much a part of the protagonists’ lives been overlooked in the film?

The answer to this last question is mostly yes – but not entirely. And that the politics that does remain is obscured by the late twentieth century lens through which the story is seen. Or rather, the politics is wrapped up almost exclusively in the depiction of the sex lives of the five characters.

Sex, along with its counterparts romantic love and marriage, played an important role in the political philosophy that guided the actions of the Shelley circle when they congregated in Switzerland. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s motivation for fleeing to the continent in 1816 was both financial (he was looking to escape various money worries) and political. Poems such as Queen Mab, with its call for revolutionary change, had been a direct challenge to the political status quo in Britain, and marked him out as a subversive if not seditious element in society. Shelley’s soon-to-be wife, Mary Godwin, was the daughter of two of the leading political thinkers of their era, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, whose radical ideas had likewise set them apart from the mainstream of British society.

Following the premature death of Mary Wollstonecraft, Godwin had written her biography in an attempt to commemorate her life and thought. In this he laid out details of her unconventional life, including the fact that she’d given birth to her first daughter out of wedlock. As a result, both Wollstonecraft and Godwin were labelled corrupters of contemporary morals, and their names became bywords for licentious behaviour. This was exacerbated when rumours began to circulate that Godwin had ‘sold’ his daughters Mary and Claire to Shelley, after Shelley had invested money in the bookshop that Godwin ran.

Shelley himself was a huge admirer of both Godwin and Wollstonecraft, and his own philosophy had been greatly influenced by Godwin’s political treatise Enquiry Concerning Political Justice. One of the key ideas that he took from this was Godwin’s attack on the institution of marriage as a fraud perpetrated by society to subjugate men and especially women: in Queen Mab, he had written of ‘Woman and man, in confidence and love, / Equal and free’.

The screenwriter Stephen Volk talks about the making of Gothic, and its mixture of Freudian and Marxist influences:

Neil McArthur dates the invention of ‘free love’ as we understand it today to 1792, the year in which Percy Bysshe Shelley was born. This was also the year in which Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and William Godwin was writing the Enquiry, both works in which the institution of marriage was assailed and love promoted as a partnership of equals. For Shelley, the ideas in these books were a design for living.

By the end of the twentieth century, of course, ideas of free love were not nearly as politically subversive as they were in the 1810s. But in Gothic, Russell nevertheless exploits this element of the story for all it’s worth. Sexual experimentation, along with a desire to burrow into the darker corners of human emotion, are the key themes of the film.

But whereas the film depicts the lifestyles of the characters as akin to that of 1970s rock stars, complete with modern attitudes about sexual freedom, it is also full of images of unsettling eroticism which act as the catalyst for the psychological unrest which haunts their stay at the villa: Henry Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare, with its impish demon squatting on the chest of a sleeping woman, comes to life; as does Percy Bysshe Shelley’s vision of a woman with eyes in place of her nipples.

Thus it is that the sexual licence which drove Shelley’s philosophy becomes, in the story world of the film, a source not for legal or moral upheaval, but emotional anarchy.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews