For English language cinema in Wales,

1997 looked as though it would be a watershed year. It saw the release of three

fairly high-profile feature films by young directors and seemed to offer the

promise of a developing film culture that would steadily increase the presence

of Wales on international cinema screens. House of America (dir.

Marc Evans), Twin Town (dir. Kevin Allen) and Darklands (dir.

Julian Richards) were all very different in tone and subject matter, but they

all sought to ‘re-read’ some of the traditional ways of seeing Wales

exemplified by the tradition of How Green Was My Valley.

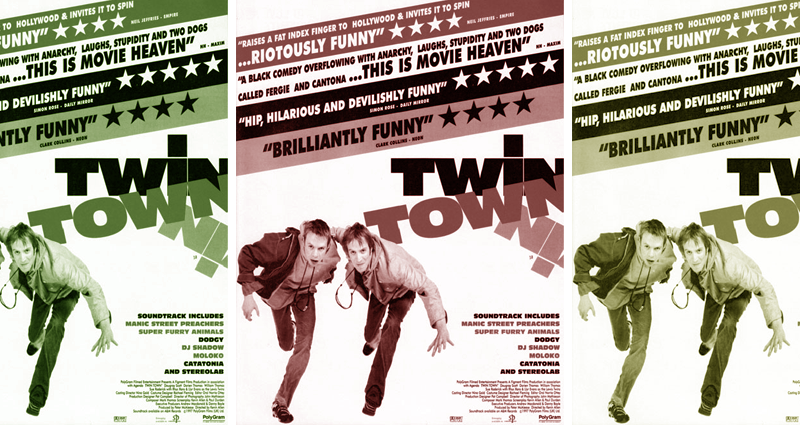

Of the three, Twin Town, reached the largest commercial

audience, and its brand of irreverent humour has ensured that its subsequent

DVD sales remained strong. However, its view of Wales and the Welsh did not

find universal approval, and its trailer gives a sense of its approach

to any traditional idea of Welsh culture:

Rugby. Tom Jones. Male Voice Choirs. Shirley Bassey. Llanfairpwllgyngyllgogerychwyndrobwllllantisiliogogogoch. Snowdonia. Prince of Wales. Anthony Hopkins. Daffodils. Sheep. Sheep Lovers. Coal. Slate quarries. The Blaenau Ffestiniog Dinkey-Doo Miniature Railway.

Now if that’s your idea of thousands of years of Welsh culture, you can’t blame us for trying to liven the place up a little can you?

(Twin Town, 1997)

It is fairly obvious then that the

film takes an irreverent look at the traditional elements of Welsh

representation, something that attracted the displeasure of a range of people,

including clergymen and the Wales Tourist Board (Morris, 1998, p. 27).

To set against these criticisms, others argued that Twin Town marked a new cultural maturity as Wales gained the confidence to laugh more freely at the parodying of its own cultural icons in a similar vein to the representation of the Irish in the television drama series Father Ted (Perrins, 2000).

House of America was a much more subtle approach to a changing sense of Welsh identity. Adapted by Ed Thomas from his stage play of the same name, the film again used some of the staple clichés of the representation of Wales – family, mining community, matriarch – and subjected them to poetic scrutiny through the filter of the leading character’s obsession with key aspects of American culture. Again, an older Wales is seen as passing away and a struggle to imagine a new one into being is taking place, this time a struggle that takes place against the backdrop of an all-pervasive American culture that surrounds us all.

The director of House of

America, Marc Evans, said that ‘In some ways House of America and Twin

Town were not the first of a new generation of films but the last of

the old’ (Evans, 2002, pp. 290–1) in that they were still preoccupied with the

stereotypes of an older Wales, even as they were undermining them. With this in

mind then perhaps we can see a slighter later film, Justin Kerrigan’s Human

Traffic (1999), as the first Welsh feature film to offer a true break

with the past and provide a new way to imagine being young and Welsh as we

approached the millennium. This break with a traditional representational past

was picked up in one of the film’s early reviews:

Just as Trainspotting makes a clean break with the traditional Scotland of tartanry and kailyard, of Scott and Barrie, so Human Traffic turns its back on the Wales of male voice choirs and the whimsical humour of The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain…it seems more like an American picture than a British one…

(French, 1999)

Human Traffic is hardly preoccupied in any obvious way with representing

national identity. It shows a group of young friends in dead-end jobs as they

live for the weekends spent in the hedonistic club scene that characterised the

late 1990s. The fact that it is set in Cardiff rather than London, Birmingham

or Manchester seems to offer the idea that Wales is emerging from a

preoccupation with an older essentialist identity and instead its young people

can feel connected to a wider international culture.

In some ways the period at the end of the nineties was a slightly false dawn in that the number of subsequent feature films to have emerged from Wales has not increased in the way that was once hoped. Nonetheless, there were important examples of films that did try to look again at life in Wales in ways that were a significant contribution to the way that the country saw itself in the context of its new political power.

This article was adapted from the free online course Contemporary Wales.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews