Find out more about The Open University’s music courses.

Festival of Massed Choirs at the Royal Albert Hall in 2018. Image courtesy of the Welsh Association Of Male Choirs.

Festival of Massed Choirs at the Royal Albert Hall in 2018. Image courtesy of the Welsh Association Of Male Choirs.

‘There are many things you can say about a Welshman,’ wrote the critic Milton Shulman reviewing the film Valley of Song in 1953, ‘but never be rude about his larynx.’ The male voice choir or ‘côr meibion’ is one of the distinctive emblems of Welsh identity, often cartoonishly depicted as elderly men in blazers, pale, male and stale. There are over eighty male choirs in Wales today and they are not going gentle into anyone’s good night; they are here to stay.

A male voice choir is divided into four parts: two tenor sections and two lower, baritones and basses. It is claimed that to sing tenor you need a falsetto voice, to sing bass a false set o’ teeth. Either way, male choirs at full throttle or in purring pianissimos, with wide dynamic contrasts in rousing operatic choruses interspersed with numbers from musical theatre, robust arrangements of national airs, plaintive love songs like the immortal ‘Myfanwy’, and inspiring hymns with their thrilling ‘Amen’ climaxes which are embedded in the Welsh cultural tradition - these never fail to engage the emotions of even the most dispassionate listener.

It is with the industrial history of Wales that the popular mind associates the Welsh male voice choir, and the popular mind is right. Its origins can be traced back to the middle of the nineteenth century. Beginning as offshoots of mixed voice choirs, male-only ensembles soon acquired a self-standing presence of their own, varying in size from glee parties of twenty to mighty phalanxes over a hundred strong. We are reminded of what Aneurin Bevan once said: culture comes off the end of a pick. A hundred years ago there was no shortage of picks when a quarter of a million coalminers were employed in south Wales and ports like Cardiff and Barry made the Bristol Channel as economically significant as the Gulf of Oman is today. And it was not only the south Wales coalfield that contributed its rich weave to this choral tapestry. Allegedly, while coal dust produced the distinctively ringing top tenors of south Wales, it is to their slate quarries that the thunderous basses of north Wales owe their comparable resonance.

Industry was the determining factor: while the quarrymen of Bethesda and Blaenau Ffestiniog are one side of the coin, on the other its collieries produced the Rhondda’s famed choirs of Pendyrus and Treorchy, while in west Wales the poured molten metal of the metallurgical works of the Swansea district contributed to the mellow tones we associate with Dunvant and Morriston Orpheus; along the northern rim of east Glamorgan and Gwent the still extant choirs of the iron-making townships of Dowlais, Rhymney, Tredegar and Blaenavon are reminders of a ruthless exploitation which nevertheless gave birth to a workforce who found powerful comfort in the consolation of music and the comradeship of song.

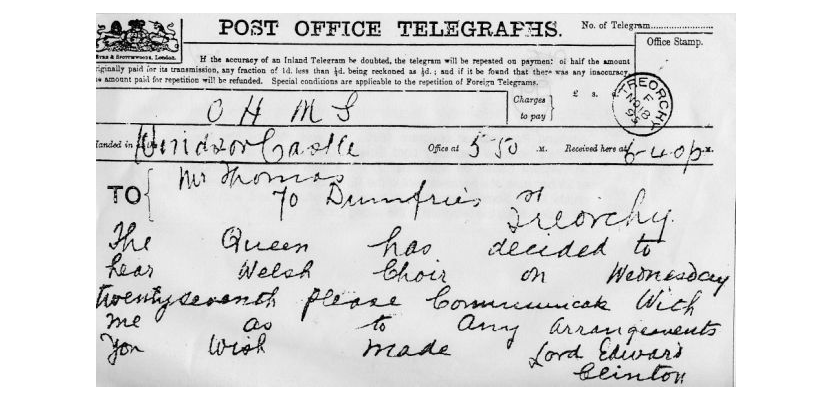

Treorchy Male Choir receive the Queen's royal command to appear at Windsor Castle in 1895. Image: Treorchy Male Choir.

Treorchy Male Choir receive the Queen's royal command to appear at Windsor Castle in 1895. Image: Treorchy Male Choir.

Initially most of those thousands who had poured into the valleys seeking employment were migrants from rural Wales, bringing with them their culture, their language, their nonconformist religion, and their fondness for harmonised singing. They were young often single men who on arrival took lodgings where they were given the room next the front door. After work they went through it in search of recreation, entertainment and the company of young men like themselves, for men outnumbered women in the early years which explains much of the masculine culture that is still a feature of the valleys even today.

Male choirs often have female conductors, like Morriston Orpheus conducted by Joy Amman Davies (image courtesy of The Morriston Orpheus choir).

Male choirs often have female conductors, like Morriston Orpheus conducted by Joy Amman Davies (image courtesy of The Morriston Orpheus choir).

Heavy industry bred pride in manual skill and intense loyalty among its workers to their ‘butties’, their villages and valleys, and to the collective institutions that represented them and received their unwavering support: the union, the lodge, the miners’ institute, the football team, the band, and the choir - especially the choir. It was an assertion of working-class male bonding and identity expressed through that most democratic and inexpensive instrument, the human voice.

When some choirs inevitably folded in the face of acute economic hardship, others took their place, like Cwmbach from the Cynon valley formed in 1921, and Pendyrus in 1924. Both, like the older Treorchy choir (1885) survive to this day, though in the depths of the inter-war Depression 80% of Pendyrus’ hundred and fifty choristers were unemployed. They turned to the fellowship of the choir to see them through, and though King Coal would never recover his throne, his choral legacy lives on.

Pontarddulais Male Choir on field at the Millennium Stadium during the 2005 Six Nations Championship prior to the Wales v England game (image courtesy of Pontarddulais Male Choir).

Pontarddulais Male Choir on field at the Millennium Stadium during the 2005 Six Nations Championship prior to the Wales v England game (image courtesy of Pontarddulais Male Choir).

The popular appeal of Wales’ male voice choirs survives even though the industrial flood tide which gave rise to them has receded into history. Whether heard in the local memorial hall, on the competitive eisteddfod platform, in great auditoria like Cardiff’s Millennium Centre or Principality Stadium, London’s Royal Albert Hall, the Sydney Opera House or New York’s Carnegie Hall, on disc or DVD, they remain for many the focus and expression of a people’s identity and national pride.

About the author

Professor Gareth Williams is one of Wales's leading social historians. A well-known writer and broadcaster who has published widely on the history of Welsh popular culture, he is an Emeritus Professor at the University of South Wales and a member of one of Wales's most famous choirs, Pendyrus.

To read more about the compelling story of Welsh male voice choirs, his book Do You Hear the People Sing? The Male Voice Choirs of Wales is available now.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews