Find out more about The Open University’s music courses.

When does a song become a national anthem? Some have been written for that purpose (France), others have been adopted (Scotland). Many take the form of a prayer or supplication (England), and some are a call to arms (Ireland), but it was the rural ballad ‘Glan Rhondda’ (‘The Bank of the [river] Rhondda’) that evolved to be Wales’s national song.

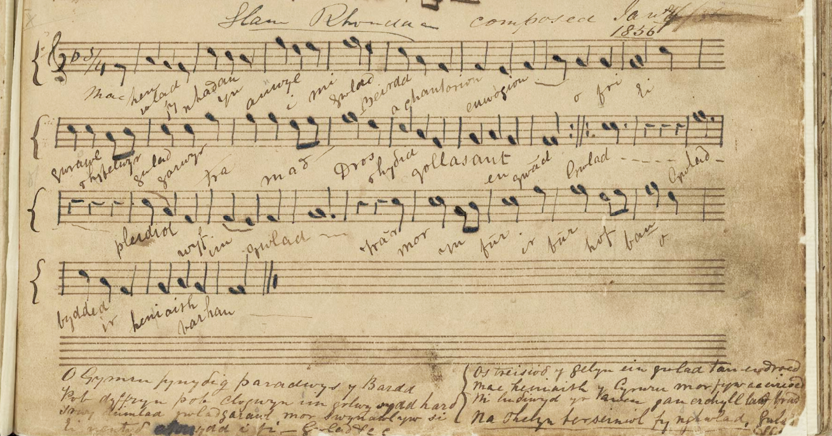

The earliest known copy of ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’ in the hand of its composer. It has the title ‘Glan Rhondda’ and is given as a single melody (no harmony or accompaniment) with words. The words of the seldom-performed second and third verses are written at the bottom of the page. (Image: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales)

The earliest known copy of ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’ in the hand of its composer. It has the title ‘Glan Rhondda’ and is given as a single melody (no harmony or accompaniment) with words. The words of the seldom-performed second and third verses are written at the bottom of the page. (Image: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales)

Its passage to that status gained momentum from a remarkable series of events that unfolded in March 1884. At the conclusion of a St David’s Day dinner at the recently opened University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire, students and staff had stood to sing the song that had come to be known by its opening words: ‘Hen wlad fy nhadau’ (‘Old land of my fathers’). It was written in 1856 by the father and son Evan and James James of Pontypridd as a romantic homage to the Welsh heritage: its poets, its musicians, and its language. A distinctive feature is its central pause for the poignant refrain ‘Gwlad! Gwlad!’ (literally ‘Country! Country!’).

The report of the St David’s Day dinner in the Cardiff press was routine, but it prompted a letter in the South Wales Daily Post from Frederick Atkins, an Oxford-educated, English-born, Cardiff organist using the self-appointed title ‘Professor of Music’. He claimed that ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’ was not Welsh at all, but a plagiarised version of a folk song that had been enhanced by the English composer Thomas Dibdin: it was a ‘note for note’ forgery to which seditious, nationalistic Welsh words had been added. The ensuing correspondence quickly gathered pace. James James swore to its originality, experts were consulted, and tempers ignited. Atkins had both form and attitude – his anti-Welsh sentiments were often aired; but this intervention touched the popular nerve.

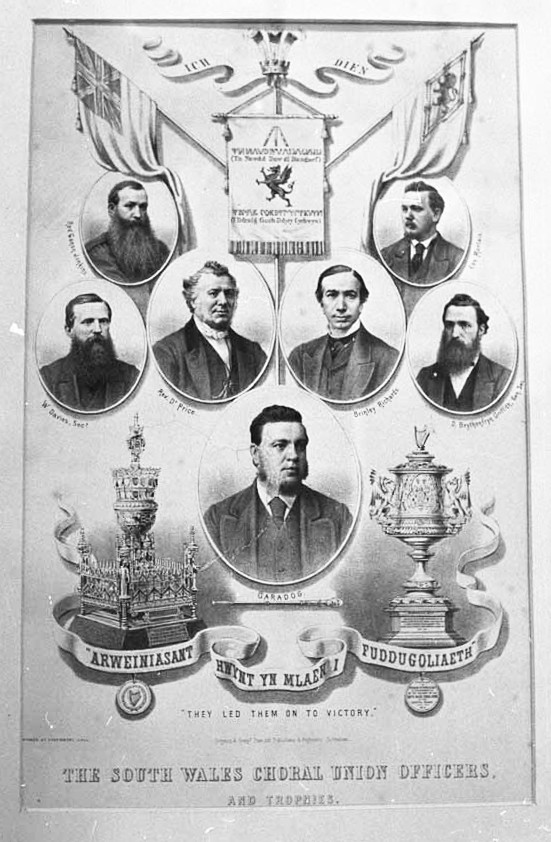

It was a great story and newspaper editors delighted in the rising circulation figures, but all stories have a shelf-life and the conclusion to this one was signalled in the Western Mail with the announcement that the ultimate authority was to be consulted; furthermore, it was to be done ‘by telegram!’. The ‘authority’ was Griffith Rhys Jones (1834-97) known ubiquitously as Caradog. A former blacksmith from Trecynon and a brilliant musician, he became a national hero as conductor of the 450-voice Côr Mawr (the Great Choir) that was assembled from across south Wales in the summers of 1872 and 1873 to compete at the Crystal Palace. The choir won in both years, making a decisive impression on London audiences. It was the first time Wales had been popularly represented in any competitive event, so the victories had national importance. Many saw it as validation of the fabled claim that Wales was ‘the land of song’.

Caradog’s response to Atkins was peremptory: claims of plagiarism were entirely without foundation. The story closed, Atkins was humiliated, and the song continued its path to immortality. The melody had been written by James, the son, the words by Evan, the father. The handwritten sources and the historical context suggest it was performed lyrically and reflectively to an improvised harp accompaniment - not dissimilar to the soft strumming of a guitar. It was published in Ruthin around 1860 with a piano accompaniment in a collection called Gems of Welsh Melody. But the Crystal Palace events initiated a frenzied interest in Welsh music outside Wales: collections of songs hit the London market and weekly Welsh Festivals were held at Covent Garden.

It was a Victorian manifestation of ‘Cool Cymru’. ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’ was a favourite. It was often placed at the end of song books, perhaps in imitation of a growing practice in which Welsh gatherings of any importance concluded with its communal rendering. One wonders how Atkins viewed all this. His intervention in 1884 had exactly the opposite effect he had intended, and Caradog’s pronouncement had confirmed not just the authenticity of the song, but in a much deeper sense, something that many Welsh people wanted to believe about themselves.

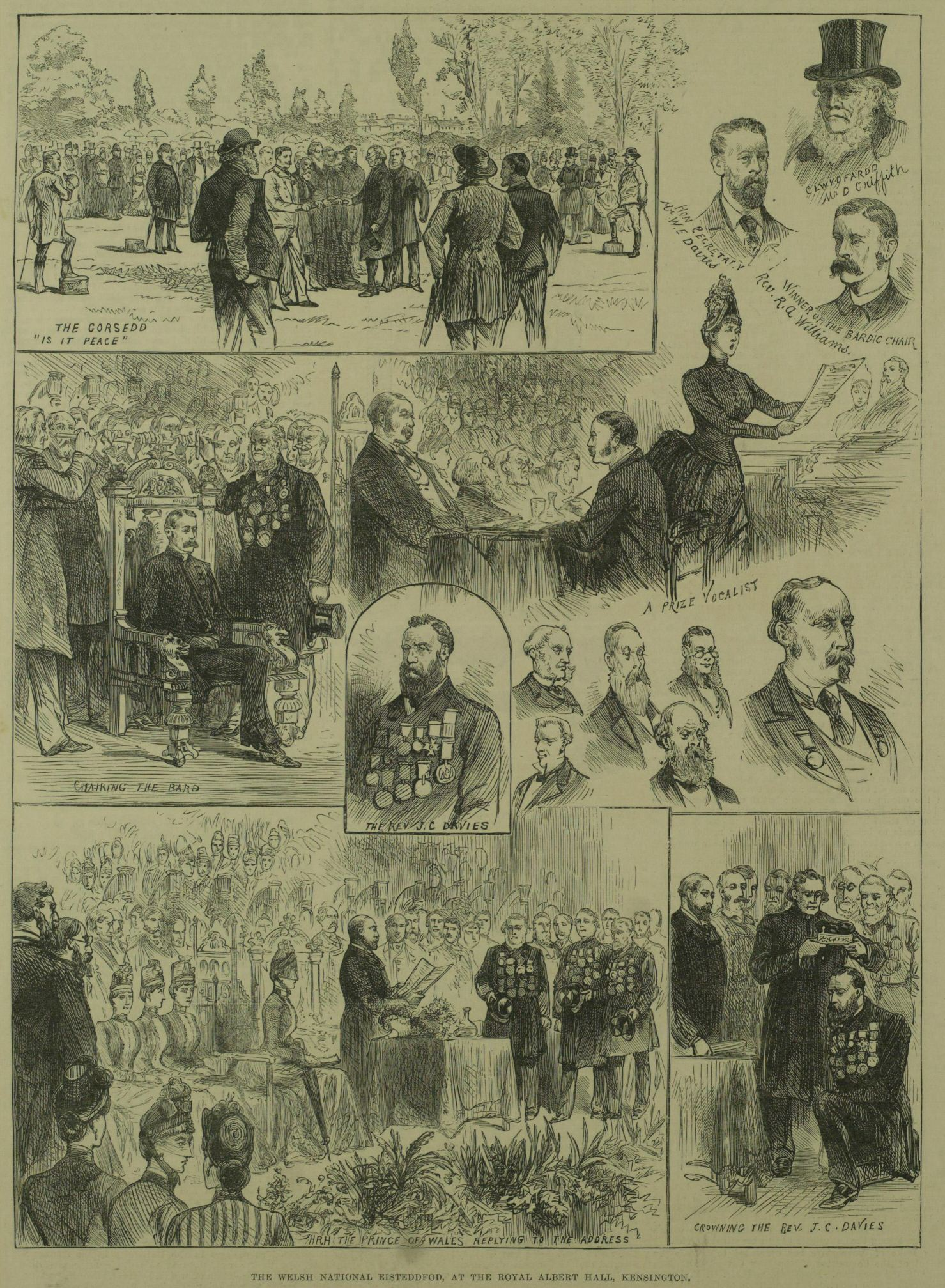

‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’ has never been officially declared the national anthem of Wales. But there was an incident that some (perhaps optimistically) believe served that purpose. An eisteddfod was held at the Royal Albert Hall in 1887 and predictably it ended with the singing of ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’. In the royal box was the Prince of Wales, eldest son of Queen Victoria and heir to the throne. It did not go unnoticed that at the sounding of the very first chord, he had risen to his feet as a mark of respect. This was surely a sign: Wales, a country with no administrative autonomy but possessed of an unambiguous cultural identity, now had its own national anthem.

An image from The Illustrated London News coverage of the Welsh Eisteddfod at the Royal Albert Hall in August 1887. It was at this event that the Prince of Wales allegedly stood for the singing of ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’. (© Illustrated London News Ltd. All rights reserved.)

An image from The Illustrated London News coverage of the Welsh Eisteddfod at the Royal Albert Hall in August 1887. It was at this event that the Prince of Wales allegedly stood for the singing of ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’. (© Illustrated London News Ltd. All rights reserved.)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews