4.4 ‘Erlkönig’ (‘The Erl-king’, 1815)

Exercise 6

Before continuing with the course, read the English translation of ‘Erlkönig’ by clicking on the link below. The translation attempts to stay close to the rhythm and rhyming-scheme of Goethe's poem, and should therefore give you a fairly good idea of the character of this famous ballad.

Click to open the words to ‘Erlkönig [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ’

Schubert wrote ‘Erlkönig’ only a year after ‘Gretchen’. Schubert's friend Josef von Spaun left a description of how he wrote ‘Erlkönig’ on 16 November 1815, after reading Goethe's poem:

We [von Spaun and Johann Mayrhofer] found Schubert all aglow reading the ‘Erlkönig’ aloud from a book. He walked to and fro several times with the book in his hand; suddenly he sat down, and in no time at all the wonderful ballad was on paper. We ran to the Konvikt [the school where they had both been pupils] as Schubert had no piano and there, the same evening, the ‘Erlkönig’ was sung and wildly acclaimed. Old Ruzicka [Schubert's music teacher at the school] then played through all the parts himself carefully, without a singer, and was deeply moved by the composition. When one or two of the company questioned a recurring dissonant note [at the boy's cries of ‘Mein Vater'], Ruzicka played it on the piano and showed them how it matched the text exactly, how beautiful it really was and how happily it was resolved.

(Quoted in Fischer-Dieskau, 1976, pp. 48–9)

The Schubert scholar Maurice Brown argues convincingly that this story must contain some elements of myth. It is well established that Schubert did have a piano, so there would have been no need to rush to the school (nearly an hour's walk away). And even if the song had completely formed itself in Schubert's mind, it would have taken him a long time to write it all down sufficiently clearly for his teacher to examine it in detail (a slightly longer song, composed in the same year, has a note on the manuscript that it took Schubert five hours to write). Brown suggests that the story is probably constructed from separate events which have been brought together – finding Schubert pacing up and down with Goethe's text, the completion of the song, and the showing of it to Ruzicka (1966, pp. 46–7).

Whatever the truth of Schubert's writing of ‘Erlkönig’, it scored an immediate success, and is one of the few of his songs that became well known during his lifetime. It was already one of Goethe's best-known poems, and several composers had set it to music, including Goethe's associates Reichardt and Zelter. Goethe took an old German legend about an evil goblin that abducts children, and wrote it in the style of a Scottish ballad. Ballads were one of the forms of folk poetry that Goethe's mentor, Gottfried Herder, helped to make popular in Germany. One of the inspirations for this fashion was Bishop Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765), which included one of the most famous old Scottish ballads, ‘Edward’ (of uncertain origin). Herder had translated ‘Edward’, and Schubert set that translation as a song too.

Goethe's ‘Erlkönig’ was always intended to be sung, and it occurs in his play Die Fischerin (The Fisherwoman, 1782). The stage direction reads:

Scattered under tall alder trees at the edge of the river are several fishermen's huts. It is a quiet night. Round a small fire are pots, nets and fishing-tackle. Dortchen sings at her work: ‘Wer reitet so spat … ‘

(Quoted in Fischer-Dieskau, 1976, pp. 48–9)

The actress who played the part of Dortchen at the premiere wrote her own simple eight-bar melody, which she repeated for each verse. The effect must have been somewhat like that of Patti Clare, who plays Gretchen in the recording of Faust on Audio 6 (track 6), humming ‘A king of a Northern fastness’ as she undresses. Goethe stated his own view on the realisation of such songs where they occur in his dramas:

The singer has learned it somewhat by heart and recalls it from time to time. Therefore these songs can and must have their own, definite, well-rounded melodies which are attractive and easily remembered.

(Quoted in Fischer-Dieskau, 1976, pp. 48–9)

Schubert has lifted the song completely out of this original dramatic context, setting the drama of the ballad itself with extraordinary power.

Exercise 7

Listen to ‘Erlkönig’ in the two recordings, one sung by a man, the other by a woman. Follow the poem and its translation as you listen. Then consider the following questions:

-

How does Schubert use the piano part to conjure up the scene?

-

How does Schubert distinguish between the three speakers – the father, the child, and the Erl-king? Consider, in particular, the lengths of the phrases that they sing, and the pitch at which they sing them.

Click below to listen to Erlkönig (male version).

Click below to listen to Erlkönig (female version).

Click to open the words to ‘Erlkönig’

Discussion

1. As in ‘Gretchen’, it is the piano that sets and maintains the scene vividly. The right hand hammers away relentlessly at repeated notes, and continues to do so through most of the song. (From the second bar onward, diagonal strokes through the stems of the notes indicate that the pattern of bar 1 is to be repeated – a conventional abbreviation.) A little rushing figure in the bass is also repeated again and again. Even before the mention of horse-riding in the first line of the poem, a feeling of urgency, perhaps even fear, has already been established. This is typical of Schubert's way of establishing tone and atmosphere: he takes an element of the poem, in this case the rhythm of a horse galloping, and uses it to create a motif which vividly establishes the mood of the poem, and provides a sense of unity through the whole of the song.

2. This is more difficult to answer, because of the way that singers add characterisation of their own to what Schubert has written. Naturally a singer will tend to sing the father's passages in a solid, manly way, the child's part in a lighter, more childish tone, and the Erl-king in a wheedling and spooky manner. It also makes a difference whether it is a man or a woman singing it. Since all the characters in the song are male, a male singer tends to give more sense of actually impersonating the characters, particularly the father. A woman singer inevitably tends to give more the impression of telling the narrative, with less sense of actually being the different characters. Nowadays it is more often sung by a man than by a woman, though both male and female singers performed the song in Schubert's lifetime, and of course Goethe originally intended the ballad to be sung by an actress on the stage. And it was a woman, Wilhelmine Schroder, who sang it to Goethe after Schubert's death and persuaded him that it was a great song (too late to benefit Schubert, alas). There is even a report of Schubert taking part in a performance with three singers while he and Vogl were staying with a musical family on a visit to Steyr: Schubert sang the part of the father, Vogl that of the Erl-king, and the 18-year-old daughter of the family that of the boy.

After that preamble, how does Schubert's music distinguish between the father, the boy, and the Erl-king, quite apart from how the singers characterise them? The most striking difference between them is that the Erl-king is the only one of the three who gets a real, continuous melody. And, until the very end of his part, where he threatens force, his melodies stay in major keys. By contrast with the Erl-king, the boy and the father have only short, disjointed phrases, almost always in minor keys. The Erl-king's smooth melodies sound sweet and agreeable, and in the context of the song, that is what makes them sinister. He sounds at ease, and his very fluency suggests that he is the one in control of the situation. The Erl-king's lines are also the only parts of the song where the hammering of the piano part relents, switching to a more easy-going rhythm. You can see this in the score: at ‘Du liebes Kind’, in the right hand of the piano, Schubert leaves out the first of each group of three notes, and has the bass playing a short note on each beat, as if the horse has settled into a comfortable rhythm. At the Erl-king's next entry, ‘Willst, feiner Knabe’, the right hand of the piano stops its hammering altogether, and plays easy-going arpeggios, up and down, giving almost the lulling effect of a cradle-song. And the third time the Erl-king sings, the bass of the piano remains static, playing long notes, while the right hand continues its hammering, but pianissimo. This gives a great sense of tension, which then bursts out at the boy's final cries of ‘Mein Vater’, where Schubert gives the marking fff (even louder than fortissimo).

It was the Erl-king's lines that most struck contemporary listeners to the song:

The cradle-spell that speaks from the melody, and yet at the same time the sinister note, which repels while the former entices, dramatises the poet's picture.

(Deutsch, 1946, p. 254)

The German novelist Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (known as Jean Paul) was reported to be particularly moved by the Erl-king's passages in the song: ‘the premonition of secret bliss, suggestively promised by the voice and the accompaniment, drew him, like everyone else, with magic power towards a transfigured, fairer existence’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 511).

The father's short phrases are pitched quite low in the singer's voice, and that adds to the impression of a man who is at least trying to remain calm, and cannot see what his son can see. If he is alarmed, he is certainly not going to show it. The boy's phrases are also short, but they are higher in pitch, and they get higher as the tension mounts. His cries of ‘Mein Vater, mein Vater’ are pitched a step higher each time: up to E flat the first time, F the second time, and G flat the third and last time, the highest note in the whole song. Each time this phrase occurs, it clashes discordantly against the relentlessly hammered-out notes in the right hand of the piano part (the touch that Schubert's teacher Ruzicka is said to have admired). And each time the phrase is exactly the same. This, together with the rising pitch, the dissonance and the sudden return to the hammering of the piano, gives a vivid sense of increasing desperation.

The ending of the song is dramatic in a subtle way. After the climactic cries of the terrified child, and then the father's accelerating gallop, they finally reach home. The climax of the story is delivered quietly and simply: the boy was dead. The extremely ‘undramatic’ setting of this line is extraordinarily effective. Goethe has already given the clue to it, by switching for the first and only time in the poem to the past tense. If he had written ‘the child is dead’, it would have had quite a different effect. By writing ‘the child was dead’, the narrator steps out of the story, as if closing the book and saying, ‘I don't have to tell you the rest. Of course the boy was dead.’ Schubert's underplayed setting of this ending enhances that effect.

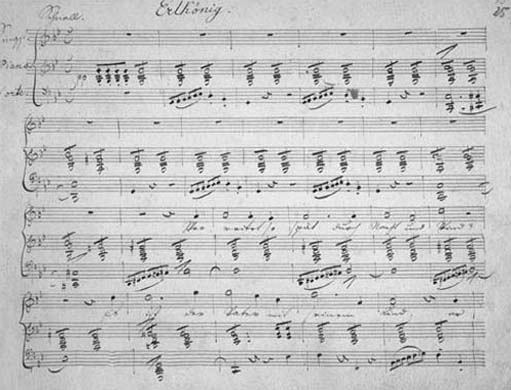

Schubert wrote several drafts of this song before arriving at the version which is now always performed. (This in itself counts against von Spaun's story of Schubert dashing the perfected song down at one sitting.) Most of the others are different in fairly small ways. In all of them, the beginning is marked pianissimo, whereas in the final version it is forte from the start so that the song begins straight away with the emphatic pounding of the horse's hooves. One version has a more fundamental difference, and the first page of Schubert's manuscript of it is shown in Figure 5. As well as having the soft opening, it simplifies the ferociously difficult piano part, giving the right hand only two notes per beat instead of three. This easier version is never played nowadays. But it is in this form that Schubert himself used to play it (he was not a great virtuoso pianist, unlike Beethoven), and it was this version that was sent to Goethe in the package that the poet never looked at. The opening bars of this simplified version of the piano part are played on audio link below.

Click below to listen to Erlkönig, opening bars of Schubert's simplified piano-part (Robert Philip, piano).

This manuscript also shows that Schubert used a shorthand to save time when writing. As in the final version of ‘Erlkönig’, the repeated notes in the right hand of the piano part are written out only at the beginning. After that, he writes a succession of minims (long notes) with a diagonal stroke through them, to indicate that each note is to be subdivided in four, as in the first bar. Does this make it more likely that Schubert's first draft could have been ready ‘in no time at all'? Perhaps.

‘Erlkönig’ ‘was the first song by Schubert that Vogl sang at a public concert, in a theatre in Vienna in 1821. Schubert accompanied him at the rehearsal, and was asked by Vogl to add a few bars in the accompaniment so that he had enough time to breathe. It is not clear whether these extra bars were incorporated into the published version that we now know. Vogl's performance at the concert was a great success, and was encored. A review reported that ‘[s]everal successful passages were justly acclaimed by the public’ (quoted in Deutsch, 1946, p. 166), which suggests that the audience applauded during the performance, more like a modern jazz audience than the silent audience at ‘classical’ concerts. (Many reports during the nineteenth century indicate that this was quite normal in concerts of the time.)