2 Robinson Crusoe

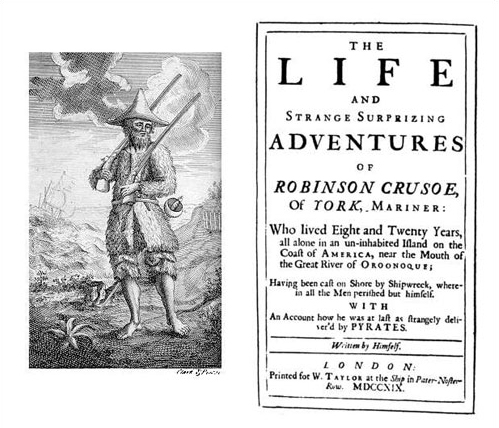

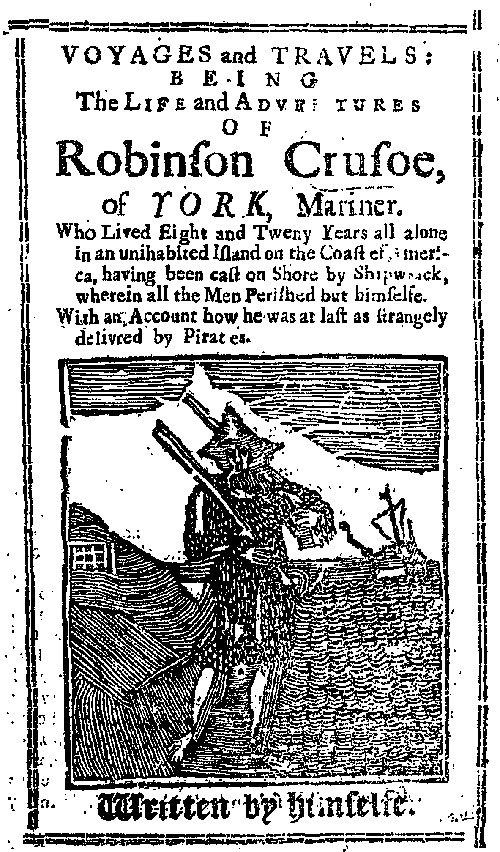

From the moment of its first publication in April 1719, Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe was a commercial success. By the end of the year five further editions had been published, and pirated copies and abridgments had already begun to appear (a sure sign of real popularity). It went on to become one of the most frequently published novels in the English language, with nearly 1,200 separate editions up to 1979. It also attracted imitations, which were produced in such large numbers that they form an identifiable genre known as the Robinsonade. Among the most famous of these Robinsonades were works like The Swiss Family Robinson by a Swiss clergyman Johann David Wyss, translated into English from German in 1814, and The Coral Island (1858) by the Victorian children’s writer R. M. Ballantyne.

Many scholars have attempted to account for the extraordinary popularity of Robinson Crusoe and its imitations, and have speculated about what it was that readers were responding to in Defoe’s book. Pat Rogers, to take one example, made an intensive study of the history of publication of Robinson Crusoe in chapbook form, looking particularly at what was included or omitted in these cheaply produced and radically shortened versions of the novel.

Rogers concluded that the readers of these chapbooks were responding to Robinson Crusoe as ‘a story of survival, as an epic of mastery over the hostile environment, as a parable of conquest over fear, isolation and despair’. However persuasive this conclusion may seem, it can be little more than one scholar’s guesswork. To move beyond guesswork we need to study evidence of the responses of actual readers, and UK RED offers a quick and convenient method of accessing such evidence.

Activity 1

As a first step, please now go to the UK RED site [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] and check out how many references it contains to Defoe and to Robinson Crusoe. You can use the ‘Basic search’ facility, which searches all the fields, putting in first ‘Defoe’ and writing down the number of results, and then ‘Crusoe’ and writing down the number of results. You should then use the ‘Advanced search’ facility, in which you can go to the ‘Author being read’ box and put in ‘Defoe’, and then go to the ‘Text being read’ box, and put in ‘Robinson Crusoe’. In each case you then scroll down to the bottom of the page and press ‘Submit query’ and a new page will open with the results. These searches will give you a quick indication of the amount of material included in RED about the reading of Defoe and his famous novel. When you have done this, compare your results with mine in the ‘Discussion’ box below.

Comment

I carried out these searches of RED in September 2010. Using the ‘Basic search’ I got the following results:

- ‘Defoe’ = 139

- ‘Crusoe’ = 215

An ‘Advanced search’ gave me the following results:

- ‘Defoe’ as ‘Author being read’ = 76

- ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as ‘Text being read’ = 52

The results you get may well be different, because RED is an ever-growing resource, with new data being added all the time. But these figures give you an idea of the substantial quantity of information that is there to be studied and analysed.

You might have wondered why a basic keyword search for ‘Defoe’ or ‘Crusoe’ returned so many more results than an advanced search for the author ‘Defoe’ or the title ‘Robinson Crusoe’. The answer is that the basic keyword search looks for the specified term in every text field of the database. This means that it will return entries where ‘Defoe’ or ‘Crusoe’ are mentioned, even if they are not necessarily the author or text being read.

For instance, a reader might have purchased ‘Robinson Crusoe’ on the day they also bought ‘Jane Eyre’, but because they only read ‘Jane Eyre’ that evening, ‘Jane Eyre’ is recorded as the text being read. Or again, someone reading some other travel narrative might have been reminded of the story of ‘Robinson Crusoe’, so again ‘Crusoe’ might appear in the evidence of the experience, even though it was not itself the text that was being read.

The point to remember is that using the ‘advanced search’ to search for ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the text being read will give you very specific evidence about the reception history of Defoe’s novel; but searching for ‘Crusoe’ using the basic ‘keyword search’ will bring up all mentions of the text. This wider information might itself be of interest, and add another layer to the analysis. For example, it might be the case that ‘Crusoe’ was a book often bought or referred to, but not read; or that ‘Crusoe’ was so widely read that readers often referred to it when discussing their reading of other texts; or that ‘Defoe’ was such a famous author that he was frequently referred in discussions of reading.

Activity 2

I’d now like you to do some further searches, to begin to get a more detailed breakdown of the readers of Robinson Crusoe by ‘age’ and ‘gender’. So, return to the ‘Advanced search’ facility, and enter ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the ‘Text being read’. Then scroll back up and press the ‘Child (0–17)’ button (beside ‘Age’ under the heading ‘Reader/Listener/Reading Group’), and ‘Submit query’. Make a note of the number of entries you are given, and then go back in to ‘Advanced search’ and do the same procedure, except that this time press the ‘Adult’ button.

When you have got your breakdown of ‘child’ and ‘adult’ readers, carry out the same exercise to get information on the numbers of ‘male’ and ‘female’ readers. Remembering always to enter ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the ‘Text being read’, press the ‘male’ button in the ‘Readers’ section, and make a note of how many there are, and then do the same for ‘female’ readers, making a note of how many there are. When you have done this, compare your results with mine in the ‘Discussion’ box below.

Comment

My results (in September 2010) for the age breakdown of readers were as follows:

- ‘child’ readers = 32

- ‘adult’ readers = 15

You will note that the total here, 47, is fewer than the total of 52 we got by searching for all readers. What this means is that the age of five of the readers entered in RED is not known.

My ‘gender’ breakdown was as follows:

- ‘male’ = 41

- ‘female’ = 11