5 Male readers of Robinson Crusoe

Activity 4

I want you now to call up records of ‘male’ readers of Robinson Crusoe, and spend some time looking in detail at nine or ten of these. You are welcome to browse for yourself, but because there are many to choose from, I’d like you to include among the ones you read UK RED: 2357 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , UK RED: 2358, UK RED: 2360 and UK RED: 4325. Please make some notes on what you think we can learn from these about the ‘reception’ of Defoe’s novel. In what ways, if any, do you think the responses of male readers here differ from those of the female readers we’ve been looking at? When you have done some work on this, and made your own notes, open the ‘Discussion’ box to compare your ideas with mine.

Comment

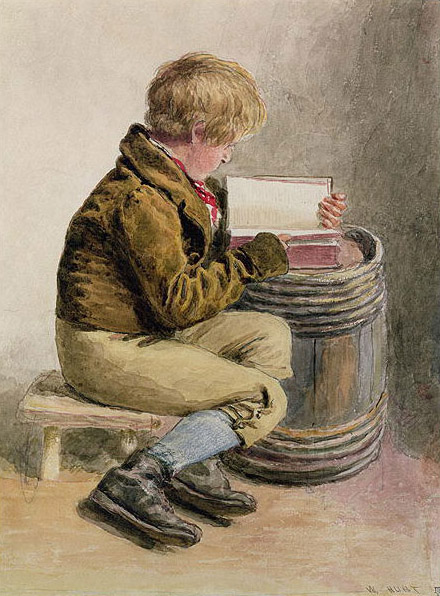

One point that strikes me is that what is remembered by many of the male readers is how reading Robinson Crusoe opened up new horizons, and inspired them to break away from their own backgrounds and circumstances. For many of these boy readers, it was, quite literally, a book that changed their lives.

So, for example, in UK RED: 2357 we learn that Joseph Greenwood, a weaver’s son, read a cheap edition of Robinson Crusoe as a child in the late 1830s: ‘To me Daniel Defoe’s book was a wonderful thing, it opened up a world of adventure, new countries and peoples, full of brightness and change; an unlimited expanse’.

Similarly, John Ward, a ploughboy who went on to become a Labour MP, remembers reading Robinson Crusoe in 1878 when he was twelve: ‘I devoured – not read, that’s too tame an expression – Robinson Crusoe, and that book gave me all my spirit of adventure, which has made me strike new ideas before old ones became antiquated, and landed me in many troubles, travels, and difficulties’ (UK RED: 2358).

Thomas Jordan describes reading Robinson Crusoe in one sitting in about 1903, when he was eleven. The book’s promise of ‘faraway places fired my imagination’ he said, and he credited it with his decision later in life to leave his job as a miner in Durham and to join the army (UK RED: 2360).

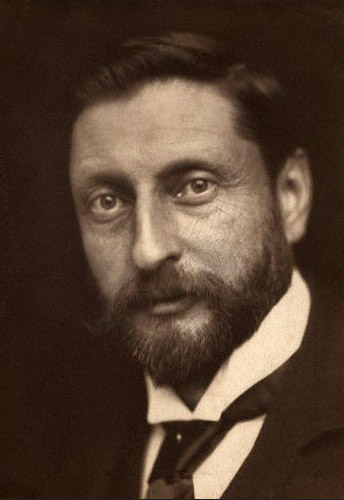

Finally, we read how H. Rider Haggard credited his own decision to become a writer of adventure books to his love of books like Robinson Crusoe as a boy (UK RED: 4325).