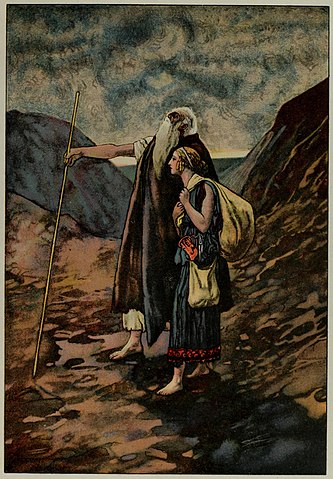

Odysseus and Euryclea by Christian Gottlob Heyne

Homer's epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey are our earliest surviving Greek literature, and our earliest sources for the Greek myths. Let's look at just two aspects of what this means.

Odysseus and Euryclea by Christian Gottlob Heyne

Homer's epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey are our earliest surviving Greek literature, and our earliest sources for the Greek myths. Let's look at just two aspects of what this means.

First, Homer gives one version of the myth, but we very commonly find different versions elsewhere – there is no single, canonical version of any Greek myth.

Second, when Homer gives at any length a myth from outside his main storyline, he gives it paradigmatically. That is to say, the myth is not given as simply a piece of story-telling, but it is told by one of Homer's speakers in such a way as to make a point, to direct his listeners to some present course of action.

An obvious example is the story, referred to repeatedly in the Odyssey, of how Agamemnon, the Greek commander-in-chief in the Trojan War, returned home after the War and was immediately murdered by his wife Clytemnestra and her paramour Aegisthus, and how in due course Agamemnon's murder was avenged by his son Orestes. Odysseus, too, is on his way home from Troy and he is repeatedly warned:

"Do be careful when you get home. Remember what happened to Agamemnon …".

At home Odysseus' son Telemachus is - somewhat slowly - growing up, and he is enjoined:

"Do be worthy of your father. Remember how Orestes …"

Now to Oedipus in Homer. His single appearance in the Odyssey is in Book 11, where Odysseus visits the Underworld, and there meets, among others, the spirit of the departed Epikaste, the mother of Oedipus. Epikaste tells him how, "in ignorance", she married her son, shortly after Oedipus had killed his father. The gods soon made this known, whereupon, while Oedipus continued to rule at Thebes, Epikaste hanged herself.

In the Iliad there is a single, glancing reference to Oedipus in Book 23, which only confirms the Odyssey version of Oedipus continuing to rule after the gods' revelation.

Oedipus' name is now a household word; and these scanty appearances in Homer cannot have had anything to do with that. Oedipus' name is now a household word; and these scanty appearances in Homer cannot have had anything to do with that. Far and away the best known version of the myth - the version from which, for instance, the founding fathers of psychoanalysis and structuralism, Freud and Lévi-Strauss repectively, drew their seminal studies - is that of Sophocles, in his play Oedipus Tyrannus, or Oedipus the King. Some 250 years or so separate Sophocles from Homer; and while Sophocles has the mother named Jocasta rather than Epikaste, he agrees with Homer that she married her son, and hanged herself when the truth came out; also that Oedipus prior to this marriage had murdered his father. But there is very little, if anything, else on which they agree.

Let's look now at a significant difference between the two versions of the story; an aspect which is important in Sophocles and is simply not in Homer at all. This shows not simply the non-canonical nature of the myths; but also how Sophocles is following a procedure which is very similar to Homer's paradigmatic use of myth.

In Homer the myth from the past is told in order to shed light on the present situation; Sophocles presents a version which tells a story from the past, but does so in such a way that it raises and reflects issues of contemporary concern, issues that are within the day-to-day experience of his audience.

Oracles do not feature in Homer, but in Sophocles they play a very important part.Firstly, there's the role of oracles. Oracles do not feature in Homer, but in Sophocles they play a very important part. It is on instruction from the oracle at Delphi that Oedipus embarks on his search for the murderer of his predecessor as king of Thebes, Laius. And when this search leads to the revelation that the murderer was none other than himself, this leads to the further revelation that a much earlier oracle, one which had foreseen that Oedipus would murder his father and marry his mother, was true – Oedipus is the son of Laius, and the son, as well as the husband, of Jocasta.

There are occasions when the reliability of this earlier oracle is called into question. Jocasta exclaims (at lines 857-8 of the play),

"So much for prophecy. From now on I'll pay no regard to it at all".

And again (977-9),

"No reason at all to fear the future. It's Chance that rules our lives, there is no certain foreknowledge of anything. Far better for us to live at random, just doing as well as we can."

Such pronouncements are horrifying to the Chorus of reverent Theban elders and they declare (895-903) that if oracles are not to prove infallible, then they will no longer need to serve the gods with their dances, and will no longer journey to the holy seats at Delphi and elsewhere. But the play does of course ultimately show that these misgivings have been unfounded – the oracles were right all along.

"Only from Death can Man not find any rescue. Even from plague he has devised escape." There is ample evidence of a gathering mistrust of oracles, and of the validity of traditional religion, in Sophocles' day. One of our best sources is the contemporary historian Thucydides who, in relating the effects of the deadly plague that struck Athens in 430 and again the following year, says (2.53) that it created a state of "unparalleled lawlessness", in which, "Men were not held back by any fear of god or law", but, "as far as the gods were concerned, it seemed to make no difference whether one worshipped them or not".

Another factor was the growing confidence, in some quarters, in the achievements of man, and a consequent feeling that there was little, if anything, that man could not achieve on his own, without help from the gods. What need, or even what grounds, were there for belief, or trust, in the gods? Do the gods even exist? Sophocles himself, in a choral ode from an earlier play, Antigone, had celebrated the spectacular achievements of man in such matters as navigation and agriculture. "Only from Death can Man not find any rescue. Even from plague he has devised escape." And the philosopher Protagoras pronounced, "Man is the measure of all things", and, "About the gods I am unable to discover whether they exist or not".

Blind Oedipus led by his daughter Antigone

This leads me to the second difference between Homer and Sophocles that I wish to consider, namely the question of who brought Oedipus' incestuous marriage to light. Epikaste is explicit that it was the gods. But in Sophocles, the moment Oedipus hears from the oracle that the murderer of Laius must be found, he springs into action himself, and single-handedly uncovers that he is himself the murderer, and also the son of Jocasta. Oedipus is behaving like Protagoran man – as though he were the measure of all things.

Blind Oedipus led by his daughter Antigone

This leads me to the second difference between Homer and Sophocles that I wish to consider, namely the question of who brought Oedipus' incestuous marriage to light. Epikaste is explicit that it was the gods. But in Sophocles, the moment Oedipus hears from the oracle that the murderer of Laius must be found, he springs into action himself, and single-handedly uncovers that he is himself the murderer, and also the son of Jocasta. Oedipus is behaving like Protagoran man – as though he were the measure of all things.

But the result of his self-imposed search is the discovery that he is not the man he thought he was – not the all-competent, all-powerful ruler of his city, but instead a man guilty of parricide and incest, and only worthy to renounce his city and his family and go into exile. (His going into exile is another flat contradiction of Homer.)

The choral ode from Antigone, after three verses celebrating man's great achievements, concludes in its final verse that for all these achievements, man will not get anywhere unless he shows proper respect for the laws of the city and the gods. In

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

That there are witches who foretell and riddles enough

Is not in question – but death-kissed lips mouth silence

Even as truths and enigmas clasp and bind -

The inextricable will not yield to spasms and spurs

All headway idle with a felled and break-neck steed.

Then as the oracle echoed and the shrine ran quiet

I pressed forward with a script - a shard – a token

There is no ordeal now that would be too unkind

For I have lived a lifetime knowing nothing or less

Suffering all and being alone and at the gates

To the waters' under world realms and here

In that marshland of old where swords are cast

Beckoning betimes in rising from the peat-stained flood

To arm the surface, vouchsafe me one meeting

To let me greet my lost father face-to-face.

Point out the causeway, follow the ancient track

Where, as the flames enveloped and the water rose

I sought him and would have borne him shoulder high

Amid the staves and spears of our perfidious kinsmen

In the thick of fighting for those that we both love:

Would that I had saved him and that he was at my back

The cloak for my wanderings and howling tempests

A man still young and fair – my brother or my son in fealty

He it was who half-prayed or half-ordered me to life

To live this sentence and make good these sentences

Wherefore must the gods and times be piteous

That my father died knowing not he had a son

And that this son still seeks him to shoulder him

Carrying him free from the dark pools and the burning

Holding close the blade that has risen from the depths

Once beckoning to our kin and held aloft among the ruins

Foretelling scions, lineage and heritage survives.

At my dread and hands the priestess ceased to tremor

Silence itself the prophesy and charm foregone

So I began in tears: ‘No ordeal can now dismay me

For I have seen the fire sweep quay and standing

And know now that all are lost, the place consumed

Our enemies taking all they cannot end for good.

And I must turn and leave the young paternal king

Set him down gently in marshes’ reddened skies

For the raiders have broken the stock from the fold

Women from their refuge and fear from the beleaguered

The thatch kindled and knives become the hunter'.

There is no manner in which I can retrace my steps

This going back is an undertaking beyond my strength

Holding the future, I cannot prevail against the past

There is a woman driven out and mute who bears me

And I must own the promise as she becomes a slave.

As the fenland darkens to the misted setting sun

Few remain of my company and there we gather

Risen from the hides where once we snared fowl

Watching the burnt piers and causeways flare and fall

To turn through the ring of dark water for the forest

Away from the weapon, token and silver depths

The garlanded maids bound for solstice sacrifice.

Still love and honour are my eternal covenant

That I could have stayed the hands of our tormentors

Or stemmed your wounds and never set you down.

For you I have grown strong, there is a band now

Of rebel warriors, captives, exiles at my command

Moving by rising moonlight on rafts of reeds and adzed oaks

Our skills honed by taking game and snaring wild fowl

And there the water village, its dogs and pigs making to sleep

Its women at the cooking pot, singing lullabies to infants

The children laughing as the old men net their fish.

Beneath the water are the sacred steels, the gifted gold

The sacrifice of metal and the bound both beautiful and base

So I cup my hands and rinse my eyes from holy springs

And catch reflection where I see you bend and smile:

We are at home now and all is well in lapping broads

That settle such straight levels linking every shore.

Balked of the raid's burning, rapine and revenge

I gently turn and slip you free beneath the mere.