Find out more about The Open University’s International Studies qualification.

Disclaimer: This is an opinion article. Please note the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the faculty the author is associated with, or of The Open University.

The movement of millions of Africans to the New World, during a period of roughly four hundred years, was by any standard, a major historical phenomenon. Rightly, accounts have emphasised the immediate impact, in terms of suffering and deaths, and the human tragedy that this represented. But there were also profound long-term consequences, which were global in scope.

To assess these consequences, we need to look at the three corners of the Atlantic’s “triangular trade”. First, what effects did the trade (and the loss of so many people) have on Africa itself? Second, how important was the trade to the development of the Americas? Third, what was the impact of the trade on Europe? Could Britain, the first “industrial nation”, have industrialised without the slave trade?

The impact of the Atlantic slave trade on Africa.

Perhaps the hardest of these areas to address is the impact on Africa, because of the lack of reliable statistical information. Historians’ estimates of the effects of the slave trade range widely, from those who see the trade as fundamental to the problems that blighted Africa both then and later, to those who see it as only a marginal factor in Africa’s historical development.

Nevertheless, it is possible to make a number of observations. Whatever the African impact of the Atlantic trade, it was at its greatest in West Africa, which supplied the largest number of captives, although at the height of the trade many other parts of Africa were also used as a source for slaves. In addition, the trade had a disproportionate impact on the male population, because male slaves were the most sought after in the Americas; it is thought that roughly two-thirds of the slaves taken to the New World were male, only one-third female.

Powerful Africans who engaged in slave dealing could make a sizeable profit from the trade, especially in view of the relatively high prices that European merchants were prepared to pay for African slaves. By the eighteenth century, slaves had become Africa’s main export.

But this may have been to the cost to African economies. It seems that the period between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries was a time of economic stagnation for Africa, which fell further and further behind the economic progress of Europe as the years passed by. Little wonder, then, that some historians interpret this as a sign that the Atlantic trade was seriously holding back Africa’s economic development.

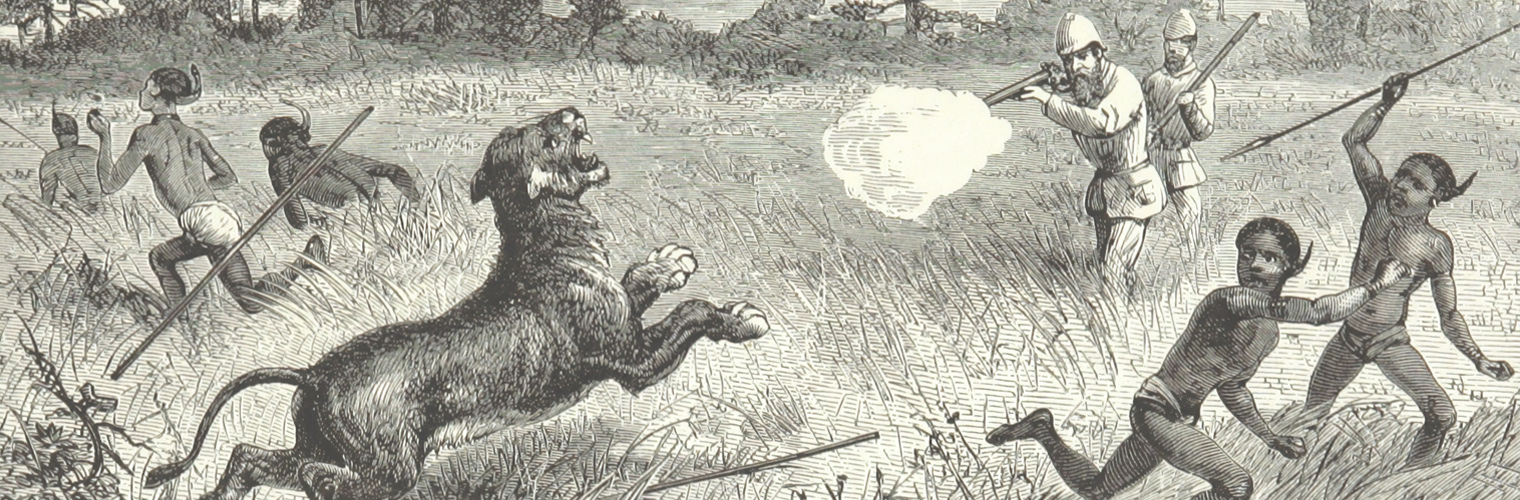

The possible negative consequences of the trade were not only economic. Politically, as African rulers organised the capture of slaves, traditions were created of brutal and arbitrary intervention by the powerful in people’s lives. Meanwhile, as rival African rulers competed over the control of slave capture and trading, wars could result. On both counts, the Atlantic trade badly affected the political landscape of Africa, and set disturbing precedents for the future.

Admittedly, not all the consequences of slavery for Africa can be attributed specifically to the Atlantic slave trade. Before, during, and after the era of the Atlantic trade, African rulers were capturing slaves for their own use, and for sale to the Middle East. According to the historian Patrick Manning, between 1500 and 1900, while twelve million captives were sent on the Atlantic slave ships, eight million were kept as slaves within Africa, and six million were sent as slaves to the Middle East and other “Oriental” markets. But the Atlantic trademarked a substantial expansion of the African slave system, and should still be seen as responsible for many of its evils.

The impact of the Atlantic slave trade on the New World.

Whatever the effect of slavery on Africa, there can be no doubt that the use of black slaves played a crucial part in the economic development of the New World, above all by making up for shortages of labour. Here, and in other places of European settlement, this was linked with assumptions, attitudes and prejudices about race that would pave the way for racist belief systems in the future.

The arrival of Europeans in the Americas had brought diseases that devastated local populations, which reduced the potential for securing labour from that source; and often too few Europeans came to the Americas to meet the demand for labour. This was particularly true in Brazil and the Caribbean, where people of African origin became by far the largest section of the population; it was also the case in parts of North America, although here white people outnumbered black people.

Black slaves were especially important as a labour supply for the “plantation” agriculture that developed in the New World, first in Brazil, and later in the Caribbean and the southern parts of North America. The plantation system had begun in medieval times on Mediterranean islands such as Crete and Cyprus - it was an unusually sophisticated form of agricultural operation for its day, producing sugar for the international market at a time when most of the European agriculture concentrated on the basics of local subsistence. But from its inception, it used slaves; and when plantations were set up in the Americas, black slaves became the backbone of the workforce.

The long-term economic exploitation of millions of black slaves was to have a profound effect on the New World’s history. Most fundamentally, it produced deep social divides between the rich white and poor black communities, the consequences of which still haunt American societies now, many years after emancipation.

The divide was reinforced by the determination to segregate black and white communities and discourage intermarriage, and by the reluctance to liberate black people from slavery from one generation to the next. This contrasted with the experiences of African slaves who were sent to the Middle East, where both inter-marriage and slave liberation were more common.

And yet, in spite of the trauma experienced over the course of generations, there was the creativity with which, gradually, the black communities of the Americas developed new identities, drawing on a combination of African tradition, encounters with European culture, and experiences in the New World. This would prove to be a great enrichment of cultural life and would contribute to the global culture of modern times.

The impact of the Atlantic slave trade on Europe.

The impact of the slave trade on Europe is another area of historical controversy. Some historians of the slave trade are keen to stress the ways in which the trade had significant economic effects in the home countries. However, historians of European industrialisation have often given little attention to the contribution of the slave trade, although there are exceptions. Readers are left asking themselves: is there any way of reconciling such approaches?

At the centre of the debate is the economic transformation of Britain. During the eighteenth century, Britain became the first country in the world to “industrialise”, in terms of an unprecedented economic shift towards manufacturing and commerce, and the progress of technology. These were also years of large British involvement in the slave trade. So were these two trends related?

Undoubtedly the slave trade affected the British economy in a number of ways. The British cotton mills, which became the emblem of the “Industrial Revolution”, depended on cheap slave-produced cotton from the New World; cotton would have been more costly to obtain elsewhere. British consumers also benefited from other cheap and plentiful slave-produced goods such as sugar. The profits gained from the slave trade gave the British economy an extra source of capital. Both the Americas and Africa, whose economies depended on slavery, became useful additional export markets for British manufacturers. Certain British individuals, businesses, and ports prospered on the basis of the slave trade.

However, this is a long way from saying that the slave trade was the main cause of Britain’s “industrialisation”. British economic advance was made possible by many other factors, including the progress of agriculture, the advance of technology, the stability of political institutions, the local availability of materials such as coal, and a culture that was conducive to innovation and enterprise. It is tempting to conclude that, had the slave trade not existed, Britain and the rest of Europe would still have “industrialised” during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, although the exact trajectory would have been altered.

Two further points are worth considering. First, had the slave trade been the “magic bullet” that led to industrialisation, Portugal should have been a leading industrial power, in view of its long engagement in the trade. In practice, the reverse was true: Portugal was one of the most backward industrial economies in Europe.

Second, even if the slave trade was important to Europe’s economic development at a certain stage (the eighteenth century?), this importance must have been on the wane by the time that the trade was abolished in the mid-nineteenth century because abolition seemed to have a little negative impact on Europe’s economic advance. Instead, in the decades that followed, industrialisation marched on, spreading to new parts of Europe, and experiencing new waves of technological progress.

However, as we have seen, the actions of Europeans were having an impact on other parts of the world. On this basis, might one conclude that the most significant and grave consequences of the Europeans’ involvement in the slave trade lay in Africa and the Americas, rather than in Europe itself?

Editor's note: This article was revised on September 25th, 2020 to provide extra detail.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews