The background

My mother arrived in London as a Jamaican migrant in 1951. She worked in a range of jobs for less than £4 per week to save the £86 which paid my fare to join her in London in March 1955. I arrived by boat at a Liverpool dock and asked directions to Paddington Station where my mother was waiting. I did not recognise her. She recognised me and took me home to her attic room in Islington. The next morning, we had breakfast early and it was then she told me that I was going to work in a milk shop delivering lunches.

However, my mother’s plans ended when we were leaving our house because a man, presumably from the educational authority, told my mother that I had to complete school because I was one month short of my fifteenth birthday. The local school said I was “educationally sub-normal” and I was sent to the local Secondary Modern School where I was accepted. Before I left secondary school, the headmaster of the local grammar school offered me a place, not on my academic abilities but on my cricketing abilities which he had noted in the Islington Gazette. Although my mother said she “could not afford another delay” in retrieving her £86 fare money, she relented with a smile and I started at the grammar school.

Following school, I worked as a junior laboratory technician at a college, but my boss, Professor Chapman, gave me time off to get the qualifications I needed to enter university. I applied to various universities and was rejected, but Professor Chapman helped me to get into Leicester University to study biological sciences.

After gaining an honours degree at Leicester, I had various race-related difficulties in finding a job, but I completed my PhD at Heriot Watt, which at that time was a college but my registration was at The University of Edinburgh. While working as a researcher at the Brewing Research Foundation, I discovered the process of converting barley into malt – the Barley Abrasion Process – which was patented in 1969 and used immediately by the British brewing industry.

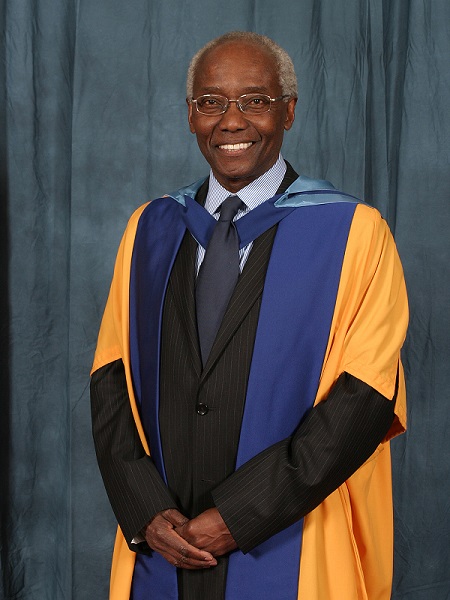

I returned to Heriot Watt University as a member of staff from 1977 to 2005 and it was a great honour for me to receive an honorary doctorate from The Open University in 2010, in Glasgow.

Since my retirement I have studied slavery links between Scotland and the Caribbean. This history is an important part of the history of the British Empire.

The history

British slave owners in the early 1800s owned about 800,000 slaves in British slave colonies. For example, Jamaica contained about 300,000 slaves and was the main producer of sugar and coffee. However, a significant amount of slave-produced cotton and tobacco came from North American slave plantations to Scotland.

The deprivation of the legal and human rights of the black people of this slavery should not be compared with other slaveries: each slavery must be defined.

Black British slaves were chattel slaves, they ‘had no right to life’ and were legally owned as property. Therefore, when British slaves were freed in 1833/34, slave owners were given twenty million pounds of compensation (billions of pounds today) because they were entitled by Law to be compensated for losing ownership of their slaves. British slavery was finally abolished in 1838.

During the enslavement of black people as chattel slaves by Britain, Scotland changed from a poor country to a rich country. About 30% of the slave plantations in the Caribbean were owned by Scots. Cities such as Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee made large fortunes from this slavery. The buying and selling of slave-produced products such as sugar, coffee, cotton and tobacco transformed the wealth of these cities. For example, the Necropolis cemetery in Glasgow was built by a slave owner and Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art was a tobacco merchant and slave owner’s house. Glasgow’s Merchant City had significant links with slavery. Many addresses in Edinburgh’s New Town are on the slave money compensation list. This means that families in these houses received financial compensation for losing ownership of black slaves in the Caribbean. Dundee had significant links with slavery in North America and in the Caribbean. The city made millions of pounds producing coarse linen, which was sold to slave owners to clothe their slaves.

Slavery money built schools, homes, railways, supported institutions and funded different kinds of commercial activities in Scotland.

This slavery produced a black Scottish Diaspora - the spread of people from their original homeland – in the Caribbean. About 60% of the surnames in the telephone directory of Jamaica are Scottish surnames and a plaid design is part of the National Dress of Jamaica. There are more Campbells in Jamaica per acre than there are in Scotland. In my family there are Scottish surnames such as La(r)mond, Wood, Walker, Elliot, Gordon and Mowatt. In the famous Bob Marley and the Wailers’ reggae band, Tosh is short for McIntosh. Other Jamaicans with Scottish names are Naomi Campbell (model), Shelley-Ann Fraser-Price (athlete) and Sol Campbell (footballer).

Glasgow University’s action in researching its links with slavery – before the recent attention to the history of our slavery – shows that institutions can lead in correcting social injustice. Its research showed that the university benefitted from slavery and it has set up educational reparative justice links with the university of the West Indies and with the local community for scholarships for black students.

Many city councils in Scotland are examining their equality policies with an aim of improving equality, diversity, inclusion and a recognition of this history. For example, The City of Edinburgh Council has produced a new temporary plaque which contains a new narrative of the political and pro-slavery activities of Henry Dundas MP (1st Lord Melville), who stopped Wilberforce from abolishing the slave trade from 1792 to 1807, causing over 600,000 Africans to be transported into British slavery.

Melville monument with statue of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, in the centre of St Andrew square, Edinburgh

Melville monument with statue of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, in the centre of St Andrew square, Edinburgh

Although many people have stated that statues such as that of Henry Dundas should be removed, my view is that if you remove the evidence, you remove the deed. Therefore, slavery-related objects such as statues and buildings should carry plaques which tell the truth of links with slavery.

In this regard, the next statue that is removed, should be racism. Teaching this history properly in schools and giving it proper attention in our higher institutions of education should help to reduce slavery-related racism.

Unlike those who have said that people are different species and races … my view is that we are one humanity, nothing less.

Discover more

Check out poet and writer Benjamin Zephaniah's interview with Sir Geoff about his journey to becoing a respected scientist: The Z files: Professor Geoff Palmer.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

Hobshawm, E. (1962 [1996]) The Age of Revolution, Vintage Books p.30

I had very little idea of the intricacies of the Scottish slave trade, in fact I don't think I've put two and two together, but this has really opened my eyes.

Thank you for sharing your findings and personal experiences. You have taught me a lot in one sitting and I'm eager to know more.