When was the last time you picked up a good book, had a boogie to your favourite song, or lost yourself in doodling or colouring? With increasingly busy lives, many of us are also more and more aware of the importance of ‘down time’, time to be creative, or to follow our passions. The power of the arts to influence our lives for good or bad has been recognised for centuries, and arts therapies form an important part of treatment for a wide range of physical and mental health conditions. More broadly, the arts can be powerful agents across society, from young to old, building community and connectedness as well as helping individuals. But what evidence is there for the ability of the arts to improve health and wellbeing, and why might they be so effective?

Arts therapies

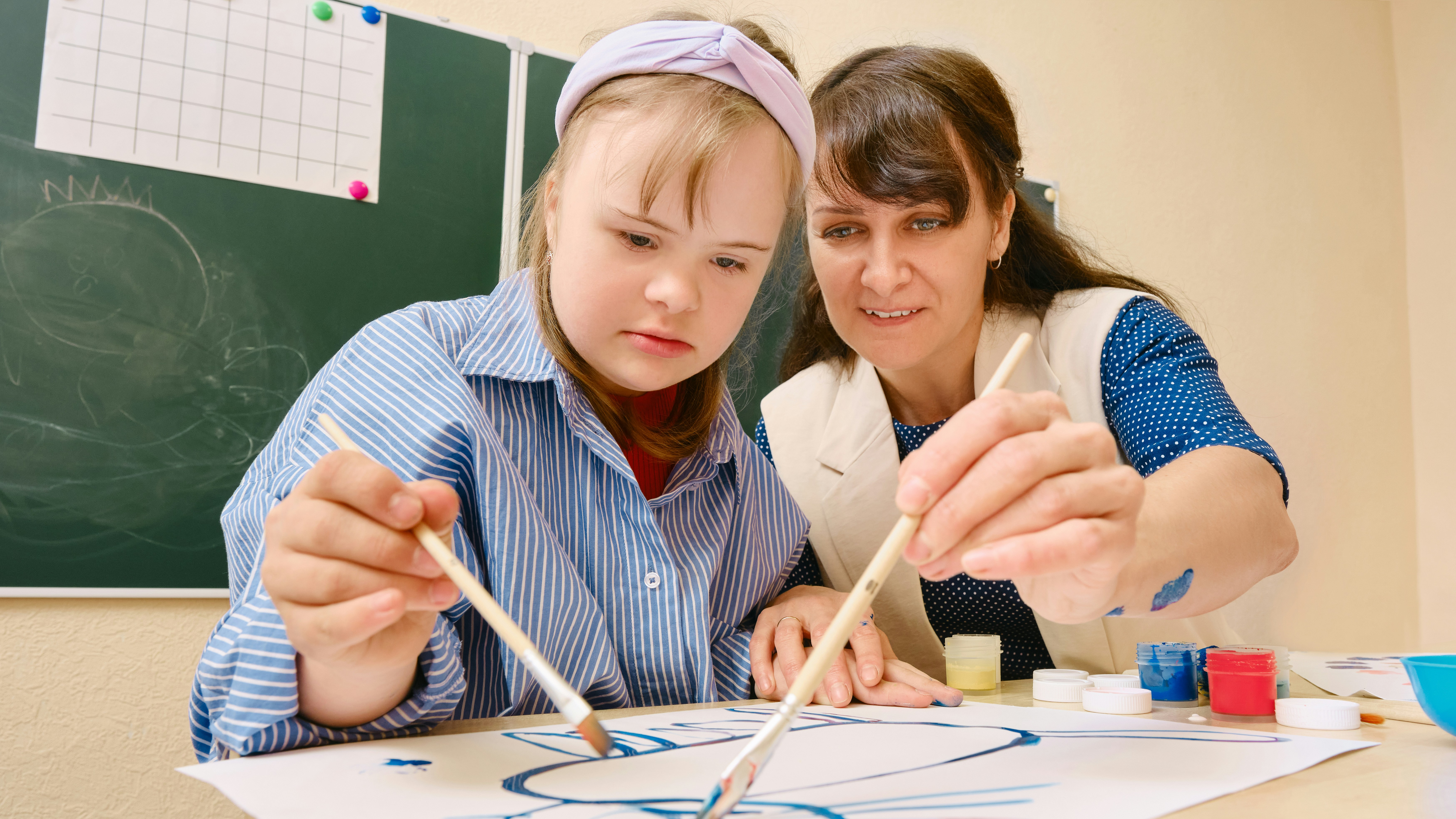

Formal arts therapies are used throughout medicine and associated healthcare practice, from babies and children needing additional developmental support, adults with physical and mental health conditions, to people with age-related reduced mobility and dementia.

A wealth of research has investigated the ways in which the brain, and other parts of the body, respond to the arts. Many art forms trigger both intellectual and multi-sensory responses, drawing on different areas of the brain. Many also invoke an emotional response, perhaps engaging with memories. Some art forms further include physical activity, such as dancing or singing, leading to improved stamina, lung health, coordination and balance. Indeed, music making has been shown to alter the structure of the brain, particularly where an instrument is learned from a very young age, as well as affecting the blood pressure, heart rate, nervous system and digestion (Fancourt, 2017, p. 34). The arts have also been used to reduce pain, both short-term and chronic. Numerous studies, for example, have experimented with using music to improve recovery after surgical procedures, which reduced levels of pain and anxiety, requiring lower levels of medication (Hole et al., 2015).

The arts are perhaps most closely connected to mental health. Research has shown that arts such as creative writing, music, and dance, have been helpful for reducing stress in a range of populations, such as refugees, survivors of abuse, and children who have experienced trauma or crisis (Carey, 2006; Malchiodi, 2020; King, 2022). Participation in the arts can also have a positive effect on people with anxiety or depression, as well as conditions such as schizophrenia, whether via a direct impact on the brain, via impact on emotions and mood, and via more general changes in behaviour, surroundings and other aspects of wellbeing (Fancourt, 2017, p. 36).

Society and community

Beyond formal arts therapies, many projects and areas of research focus on the social benefits of engaging with the arts, which has a knock-on effect on health and wellbeing. Wellbeing goes far beyond our personal health, and includes our environment, diet, activities, finances, relationships, jobs, skills, and emotions. For many people, mental and physical health are related to social aspects such as loneliness. Bringing people together via the arts is a key way of combating isolation, particularly among older people (see Dadswell et al., 2020).

The arts can also support connections and a development of both collective and self-identity. Shared participation in the arts can build understanding between different social or cultural groups, and enhance resilience within communities. Social interaction supports the development of a sense of collective or social identity and responsibility. We see this in cultural traditions and rituals from around the world, but it has also developed in new forms in the modern day. Group identity might be developed via online forums and activities around shared arts practices, for example, which are particularly important for vulnerable or marginalised groups (see Zarobe and Bungay, 2017).

Closely linked to these ideas, the arts have been used successfully in relation to trauma and conflict, to reduce social unrest, to highlight and challenge oppression and prejudice, and to support social change (Levine and Levine, 2011). Those working with survivors of conflict, violence or other forms of trauma often make use of the arts as an alternative means of approaching difficult topics or memories.

Social prescribing

One of the most significant developments related to health, wellbeing and the arts in the last few decades is the idea of ‘social prescribing’. This relates to the formal adoption of the arts and other activities, such as gardening or sports, as a part of healthcare structures. These activities can be recommended by a health practitioner and are usually organised via ‘link workers’, who are intended to form a network with community-based organisations. However, there remains debate around the concept of ‘prescribing’ the arts, which tends to suggest a medicalisation as well as something which is ‘done to’ the patient. There are also different approaches, which focus on developing the individual, the community, or both (see Drinkwater, 2025, p. vii).

Finding out more

Given the depth of evidence about the potential of the arts to aid health and wellbeing in both formal and informal settings, it is not surprising that there is a considerable amount of work going on to embed this in political and health contexts in the UK. The UK government has supported working groups on Arts, Health and Wellbeing, and on Creative Health. Their most recent Creative Health Review was published in collaboration with the National Centre for Creative Health in 2023. The National Academy for Social Prescribing supports and organises work in that area. However, there are many smaller charities and organisations which operate on a local basis.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews