This was to become the blue plaque scheme, an incredibly popular idea which has bred imitators across both the country and the world. The plaques commemorate people whose work or actions have had a notable impact on British life and have helped shape British ‘heritage’.

English Heritage Blue Plaque Commemorating Bertrand Russell.

English Heritage Blue Plaque Commemorating Bertrand Russell.

But ideas about what constitutes British heritage have altered radically between the second half of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twenty-first. So much so that schemes like this have become sites for conflicting ideas about what counts – or at least, what should count – as symbols of British cultural identity, and what role the heritage industry plays in shaping a shared narrative for the nation.

So should we be commemorating the anniversary of the inception of this commemorative scheme? Or are the ideas that Ewart had back in 1863 no longer a suitable vehicle for promoting and celebrating the dynamic, multicultural, multi-layered nature of this country’s ever-evolving heritage?

To explore this question, we carried out a research and public engagement project examining how individuals, groups and artists have been engaging with the legacy and framework of the blue plaques scheme, along with other forms of public commemoration, to broaden and challenge traditional ideas of British heritage and make public space more representative of the diverse history of the people who’ve shaped the culture.

The scheme that Ewart started back in the 1860s is now run by English Heritage. Of the 990 plaques they’ve put up over the years, 85% of them commemorate men and only about 4% are for Black and Asian people. In an interview for our project, Tony Warner, the author, historian, and founder of Black History Walks, pointed out that only 2% of the current plaques commemorate Black people whereas 14% of the population of London is African Caribbean. As he commented, ‘there’s such a disparity [here]… it’s ridiculous’.

There have been concerted efforts in recent years, both by English Heritage and by other organisations, to address this imbalance in representation. Howard Spencer, Senior Historian for English Heritage, noted in his interview with us that more women than men are now shortlisted for plaques by the organisation. But he went on to point out that with ‘current ways of working, if you only put plaques up to women, to get to equal numbers [to men], you’d have to go on for 50 years’.

Initiatives to counter these disparities include English Heritage setting up a steering group for ethnic minorities and releasing calls for the public to nominate more women. But as Tony Warner commented, measures like this could and should have been taken many years ago, ‘and so, rather than asking for someone else to put up these plaques, we just thought let’s do it ourselves’.

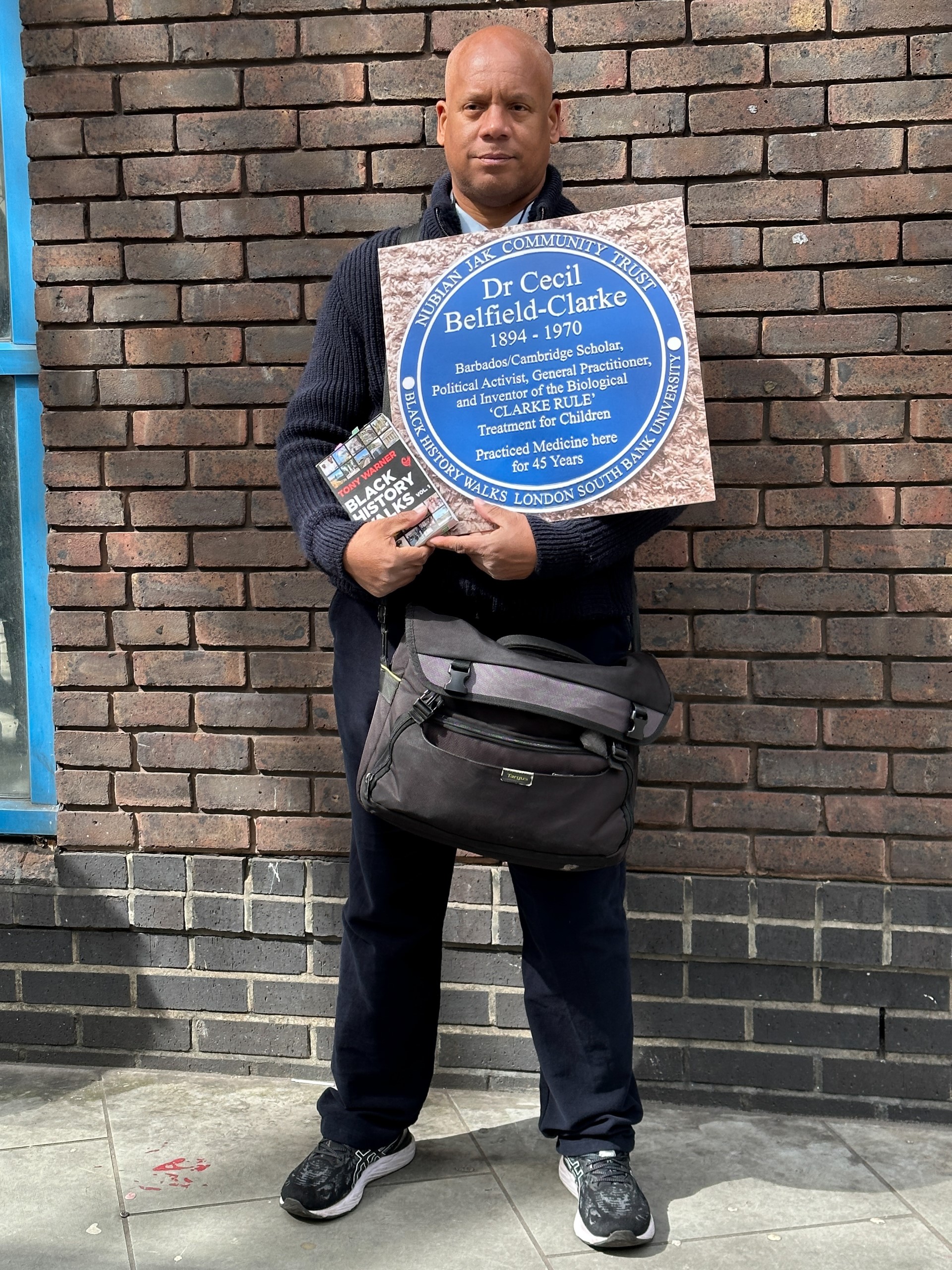

Black History Walks, along with the Nubian Jak Community Trust, thus set up its own scheme to recognise Black people who, in the words of Warner, ‘have done unusual, outstanding, amazing things that are not recognised by the mainstream’. Over the last few years, they have erected plaques to notable individuals such as Cecil Belfield Clark, Darcus Howe, Emily Clarke, Phyllis Wheatley, Harold Moody and Sarah Parker Remond. Nubian Jak and Black History Walks Blue Plaque Commemorating Dr Cecil Belfield-Clarke.

Nubian Jak and Black History Walks Blue Plaque Commemorating Dr Cecil Belfield-Clarke.

The aim behind their scheme is both to recognise these individuals and extend current understandings of British heritage more generally. Heritage has traditionally been a hegemonic concept, based around those in positions of power deciding what and who should be remembered for the benefit of the nation.

As Sara McDowell says, ‘Our landscapes are valuable documents on the power plays from which social life is constructed, both materially and rhetorically’. In recent years, however, there has been a shift to approach the concept from a more democratic, bottom-up perspective which incorporates voices from the community. It’s to this end that Tony Warner describes his initiatives as interactive, intergenerational and multi-level community learning experiences.

Tony Warner, the founder of Black History Walks.

Tony Warner, the founder of Black History Walks.

The Heritage Studies expert Laurajane Smith has argued that heritage shouldn’t been seen as something that’s ‘done or “saved”’. Instead, it’s better understood as ‘a process, practice or performance activity [that’s] tied up with the activities of remembering and commemoration that used the past to help make sense of the present’. It’s in this context that blue plaque schemes can help open up conversations about what we want to remember and what we may need to forget.

On the 160th anniversary of the blue plaque scheme, it’s a good time to rethink what legacy each plaque leaves behind. As well as what legacies are still missing from the heritage landscape so that it represents the rich and diverse world we live in.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews