6.3 Performance spaces

Dramatic texts intended for performance are, in an important sense, a ‘living’ art form. Plays are conceived with a particular space in mind, and to varying degrees the relationship between the text and its enactment is influenced by the kinds of theatre practices and spaces that have become conventionalized. Some plays lend themselves to particular kinds of performance spaces, such as Brecht's Mahogonny (1927), which carried over the boxing ring metaphor of the play's main theme to a literal method of staging: an in-the-round/arena space was specially constructed to function as a boxing ring for a performance of this play. Similarly, Jim Cartwright's modern play Road (1989) was written to be performed in a promenade performance space.

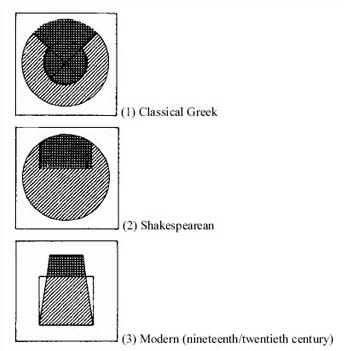

A history of the variety and development of performance spaces would show the changing social role and function of drama since its recorded origins in ancient Greece almost 3,000 years ago. It would serve to remind us that what we now recognize as the theatre is far removed from the vast open-air Greek amphitheatres capable of seating up to 24,000 people. We tend to regard going to the theatre as a much more rarefied experience than it would originally have been perceived to be, and came to be treated by play-goers in medieval times or in Shakespeare's time. We wouldn't usually associate it with a religious event, we certainly wouldn't expect to stand throughout a performance and would probably find it strange or even unnerving to be expected to participate in the action. We can trace the most significant changes in the development of performance spaces by looking at the shift in the spatial relationship between audience and performers. Figure 1 broadly illustrates the changes in the spatial relationships between what represents the ‘stage’ and what serves as the auditorium.

Activity 13

Look carefully at each, noting that the dark section signifies the performance area and the lighter section the viewing area. What is the main change you observe taking place?

Discussion

You probably noticed a gradual shift away from a spatial relationship where the audience was grouped around the stage area in an extended semi-circle, to one which had effected almost a complete separation of the stage and the audience. This break started with the introduction of the proscenium arch in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, although the proscenium curtain, used in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, made the more decisive break.

Activity 14

Look at the diagram again. What do you think some of the implications are for performance in each of the performance spaces, as indicated by the spatial relationship between audience and players?

Discussion

1. The classical model seems more akin to a modern sports stadium than a theatre. The vastness of the audience and semi-circular design of the performance space made the notion of an illusionist set or realist drama impossible. Although the acoustics were generally good, given the scale of even the smallest amphitheatre, I would say that the naturalism we associate with the drama of Ibsen, for example, which often requires intimate conversation to serve as dialogue, would be out of the question here. More appropriate is the stylized, and exaggerated, gesture-like acting which characterized classical Greek drama. This was often accompanied by symbolic costume and masks, and of course, the chorus who commented on the action, addressing the audience directly. A good example is found in Aristophanes’ 422 BCE comedy, The Wasps:

| CHORUS: | Now, ye countless tens of thousands, |

| Seated on the benches round, | |

| Do not let our pearls of wisdom | |

| Fall unheeded to the ground. | |

| Not that you would be so stupid, | |

| So devoid of common sense – | |

| What it is to have enlightened | |

| People for an audience! |

2. We probably know more about the conventions of theatre in Shakespeare's time than we do about our own, so often are they themselves the source of dramatic portrayal, the film, Shakespeare in Love, being a recent example. What this diagram shows us is the proximity between audience and performers, and we can see that the audience still has access to the stage area on three sides. Unlike the amphitheatres of classical Greece, there is close contact between the actors and the spectators, and a further key difference is that these performance areas were housed in purpose-built theatres. Audiences would have been large (the Globe could hold two thousand), and socially disparate. Given the regular interaction between performers and audience, through asides and monologues, it would have been difficult to sustain the notion of dramatic illusion. There was little in the way of set design or décor to consider, thus enabling quick and easy scene changes.

3. The relationship designated by this performance space is the one we most commonly associate with our own experience of the theatre. The intimacy of the darkened space with a brightly lit stage is conducive to the same atmosphere of voyeuristic fascination as we experience in the cinema. We remain detached from the performers, looking into ‘rooms’ whose reality is sustained by scene changes through the use of the proscenium curtain, and the drama assumes a more ‘autonomous’ function. Set design, naturalistic acting and realistic situations create the illusion of reality, thus serving the conventions of the realist drama of, say, Ibsen or Chekhov. As with the other performance spaces, this has its limitations. The playful engagement with the audience by use of asides in Shakespearean and Restoration drama is severely hampered by the distance between audience and performers in this kind of space.