Find out more about The Open University’s music courses

There is a straight line running from the anti-slavery movement and its campaign music from the 1850s, through to the jazz festivals with which we are familiar in Wales today.

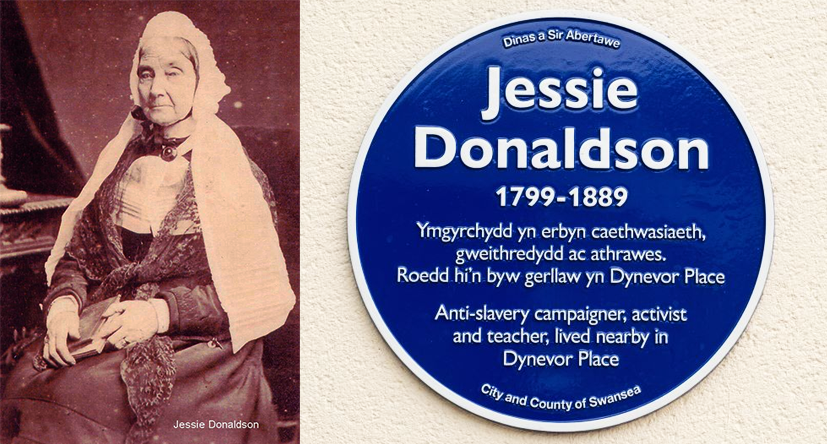

This line can be traced through the life and times of the Swansea anti-slavery campaigner and abolitionist Jessie (Heineken) Donaldson (1799–1889). Jessie had opened her School for Young Ladies and Gentlemen in her twenties in Wind Street. She was from a staunch Unitarian family who were members of the Swansea Anti-Slavery Society, the largest and most committed society in Wales. Jessie emigrated to Cincinnati aged 47, and immediately was plunged into international politics on a grand scale. Their home, Clermont, a sanctuary for runaway slaves on the Ohio riverbank, was the third Welsh safe house across the river from the plantation state of Kentucky.

Left: Welsh anti-slavery campaigner Jessie Donaldson, © Jazz Heritage Wales / Hillary Edmiston. Right: The blue plaque installed outside the UWTSD Dyenvor building in Swansea city centre to commemorate her, © UWTSD.

Left: Welsh anti-slavery campaigner Jessie Donaldson, © Jazz Heritage Wales / Hillary Edmiston. Right: The blue plaque installed outside the UWTSD Dyenvor building in Swansea city centre to commemorate her, © UWTSD.

Her

friends were journalists, freed slaves and campaigners such as Frederick

Douglass and Ellen and William Craft, and political activists William Lloyd

Garrison and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The music Jessie would have heard was

played on the Cincinnati streets by Stephen Collins Foster. He penned

abolitionist campaign songs and adapted the music and songs of the river sung

by African Americans working the tall-stack riverboats between Cincinnati and

New Orleans: ‘Oh! Susanna’, ‘Old Folks at Home’, ‘Swanee River’, ‘Old Black Joe’

etc.

Jessie returned home to Swansea in 1866 after the end of the American Civil War. She was aged 74 when The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a choir of freed slaves, arrived in town for their first performance at the Craddock Street Music Hall. Formed as a fund-raising choir for Fisk University for the Education of Freed Slaves and their children, Nashville, Tennessee, their first concert in Swansea was described as ‘strange, weird slave songs for which the slaves in the southern states are so famous’. They sold many copies of their Jubilee Song Book, giving locals the opportunity to learn their songs. A preface to the music reads: ‘Its unique origin, and that the melodies are never composed, but spring into life… and rare occurrence of triple time, or three-part measure… to be found in the beating of the foot and the swaying of the body.’ The Fisk Jubilee Singers sang with concert hall authority, so different from minstrelsy that was the popular music at the time. The Fisk Jubilee Singers toured Wales and visited Swansea again in 1875, 1882, 1889, and in 1907 as the Fisk Jubilee Trio who raised money ‘for the poor of Swansea’ in thanks for the donations paid to their Fisk campus building fund.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1875.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1875.

An early example of the intercultural cross-fertilisation of Welsh and American culture was the minstrelsy show, which between the 1850s and the beginning of the twentieth century was a highly popular form of entertainment, especially in industrial south Wales. Acknowledged today as racist and derogatory, minstrelsy shows guaranteed huge local audiences and financially benefitted the African American performers at the time. Local white Welsh minstrelsy adapted this tradition and performed in racist ‘black face’ using burnt cork as face paint, interpreting the music of the southern states of America for their own benefit. These interpretations contained banjos, percussion and dance. One local minstrel group called The Harry Collins Minstrels included one genuine Black man, among twelve men in black face. Welsh performers adapted aspects of Black music, including songs, gags and rapid-fire crosstalk, usually ending with a walkaround Skedaddle. Some African American performers, noting the popularity of minstrelsy, used make-up to exaggerate their features for extra comic effect in their own shows, which usually included versions of the Virginny Breakdown, the Tennessee Double Shuffle and the Louisiana Toe ‘n’ Heel dances. Some Welsh minstrel troupes performing in black face included a harmonium in their Skedaddles, a local touch.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, minstrelsy was evolving into the new excitement of ragtime, or raggedy time, and its dancefloor spin-off, the cakewalk, with its parody of class distinctions of upper-class mannerisms; a high-stepping, mincing walk and an arm-in-arm glide. This new musical genre was personified by the arrival in Wales of the all-Black production In Dahomey, reaching Swansea’s Grand Theatre in 1905 which caused a sensation. The show included a cakewalk competition with four couples chosen each night to compete for the dance-off prize at the end of the week, henceforth the expression ‘to take the cake’. George Walker, Adah Overton Walker and Bert Williams link arms and dance the cakewalk in the first Broadway musical to be written and performed by African Americans, In Dahomey.

George Walker, Adah Overton Walker and Bert Williams link arms and dance the cakewalk in the first Broadway musical to be written and performed by African Americans, In Dahomey.

During the First World War, a café society movement emerged which gave support and respite to those suffering bereavement. Cafés provided a convivial meeting place for women while offering new work opportunities for local musicians, dancers and entrepreneurs. There were twelve cafés operating in Swansea, the largest catering for 1,000, with some hiring small African American combos from the theatre touring productions for their afternoon floorshows and revues. Cafés competed with each other for the best in décor and floorshow, with women producing and directing the shows, as well as performing. In 1917 the popular sheet music ‘Everybody Loves a Jass Band’ was published, and ‘jazz’ first made its appearance in the south Wales press in February 1919.

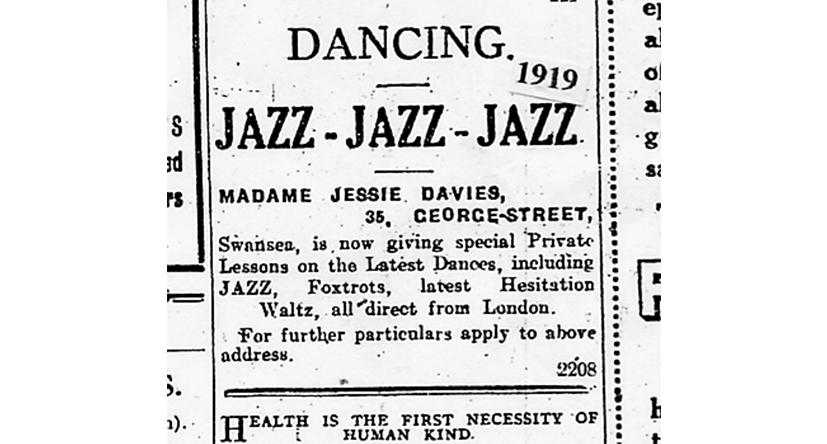

During the 1920s, dance ‘parlours’ opened in profusion, offering ‘jazz’ and ‘blues’ tuition, plus lessons in the Charleston, Turkey Trot, Chicago Maze and Swansea’s Marina Saunter with women’s bands supplying the new music. While Wales danced towards the Second World War, large dance orchestras evolved from the combos, propelling a new generation of young women leading the bands into the swing era, such as Ivy Benson and Hilda Ward, known as Lady Syncopators. A 1919 newspaper advertisement for dance lessons in Swansea.

A 1919 newspaper advertisement for dance lessons in Swansea.

During the 1920s, dance ‘parlours’ opened in profusion, offering ‘jazz’ and ‘blues’ tuition, plus lessons in the Charleston, Turkey Trot, Chicago Maze and Swansea’s Marina Saunter with women’s bands supplying the new music. While Wales danced towards the Second World War, large dance orchestras evolved from the combos, propelling a new generation of young women leading the bands into the swing era, such as Ivy Benson and Hilda Ward, known as Lady Syncopators.

The 1950s saw the ‘trad jazz’ explosion of the second jazz age, a re-interpretation of the original Dixieland music from New Orleans, which lasted until the arrival of The Beatles and the Rolling Stones in the early 1960s. Both bands recognised and paid homage to their African American blues and jazz idols. Ottilie Patterson, vocalist with the Chris Barber Jazz Band remarked ‘jazz didn’t come out of a vacuum’. Ottilie recognised that straight line running back to the old ‘weird slave songs’ of gospel music and plantation songs, as did the Rev. E. Ebrard Rees, who wrote in the Melody Maker in 1934 comparing and contrasting Welsh traditional revivalist ‘hwyl’ chanting and the African American spiritual.

This article was adapted from Jen Wilson’s book Freedom Music: Wales, Emancipation and Jazz 1850-1950, University of Wales Press, 2019.

To learn more about the history of jazz in Wales, visit Jazz Heritage Wales at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David.

About the author

Jen Wilson (1944 - 2023) left school aged sixteen having failed her 'O' levels, most notably in music and history, but with excellent RSA shorthand and typing skills. Working as a daytime secretary in shipping and coal exporting on Swansea docks during the 1960s, she also played jazz piano in clubs, pubs and concert halls, leading her own bands or as a soloist.

Her continuing education was reignited during the 1980s by joining Swansea Women's History Group with Gail Allen, led by the feminist historian Dr. Ursula Masson, making video documentaries: on Bridgend munition workers, the Miner's Strike 1984/5, Swansea Conscientious Objectors, The Last Day at Mount Pleasant Maternity Hospital, and Portrait of the Artist as an Older Woman. When Ursula asked Jen "what is the story of Jazz in Wales?" and Jen replied she didn't know, Ursula said "go and find out."

The Women's Jazz Archive, now Jazz Heritage Wales, made its appearance in 1986. This work led to Jen gaining a MSc (Econ) in Women's Studies, Swansea University (1996), an Honorary Professorship in Practice UWTSD (2016), and the Welsh Government St. David Award for Culture (2017). Her CD The Dylan Thomas Jazz Suite 'Twelve Poems' was supported by a Grant to Individuals by Arts Council Wales celebrating 50 Years in Jazz.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews