Find out more about The Open University’s music courses.

At the 1837 Abergavenny Eisteddfod, a prize was offered for ‘For the best collection of original unpublished Welsh airs, with the words as sung by the peasantry of Wales’. It was won by Maria Jane Williams, with a collection that was published in 1844 as Ancient and National Airs of Gwent and Morganwg. So far, so uncontroversial, you might think, but in fact it was significant for a number of reasons.

Up to then, collections of Welsh ‘traditional music’ had targeted a fashionable English-speaking market, presenting the tunes alone or giving them English words. To present them with their original Welsh words was to insist on the significance of the culture of the common people of Wales – in Welsh, the 'gwerin'.

The book also broke new ground as the first published example of collecting Welsh traditional songs ‘in the field’ from living, native singers who had learned them aurally: Maria Jane had collected her songs from ‘an old woman in the Glamorganshire hills now 70 years old, but still having a good voice - she learned them of her mother, who lived to 95 and so traced them back for centuries transmitted orally, never written down.’

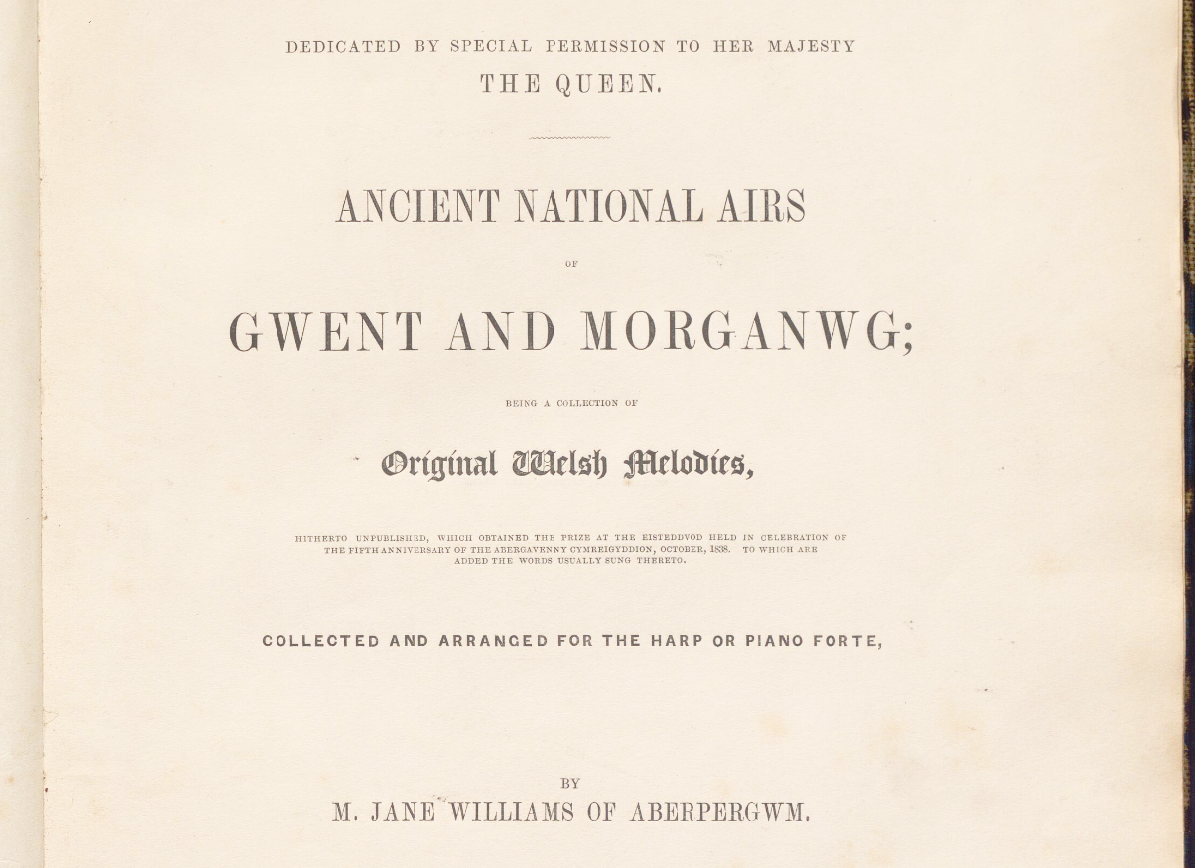

The title page of Ancient National Airs of Gwent and Morganwg (1844). Note the dedication to Queen Victoria. (Image: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales)

The title page of Ancient National Airs of Gwent and Morganwg (1844). Note the dedication to Queen Victoria. (Image: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales)

It must be said that, had it been down to Maria Jane Williams, her collection would in fact have been published in the usual way, either as the tunes alone or with English words, with an eye to the English market and the London-Welsh social circle where she was a well-known figure. She was eager for her well-connected friend Lady Llanover to obtain royal permission to dedicate the book to Queen Victoria (which Lady Llanover duly did).

However, Lady Llanover was not entirely in sympathy with her motives, commenting grimly, ‘I know well the class Miss W. is most anxious to please in London’; and it was at her insistence (she was a formidable woman) that the publication did in the end present the tunes with their Welsh words.

Left: Lady Llanover (painted in 1862 by Mornewicke), wearing the Welsh ‘traditional’ dress for which she is best known. (Image: Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales) Right: Maria Jane Williams, photographed in later life. (Image: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales)

Left: Lady Llanover (painted in 1862 by Mornewicke), wearing the Welsh ‘traditional’ dress for which she is best known. (Image: Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales) Right: Maria Jane Williams, photographed in later life. (Image: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales)

So why was Lady Llanover so keen to stay true to the spirit of the prize and retain the Welsh words to the songs? English by birth, from a family owning land in Monmouthshire, and married to Benjamin Hall MP, a south Wales landowner and industrialist, at first glance she was not perhaps the most obvious person to show an interest in Welsh folk culture.

She was, however, a great champion of the Welsh language and Welsh cultural traditions. She is often remembered now, rather condescendingly, simply as the inventor of so-called Welsh ‘traditional dress’, but her enthusiasms were wide-ranging and she was one of the key figures behind the Abergavenny eisteddfodau.

These eisteddfodau were supported by the major landowners, industrialists and politicians of south-east Wales, many of them English-born like Lady Llanover. For this class, an interest in Welsh cultural traditions and the Welsh language was not simply for its own sake, nor was it a mark of ‘nationalism’ as we would think of it today: rather they saw it as fostering a sense of what they called ‘nationality’ amongst the common people – a feeling of Welsh identity based on the Welsh language and cultural traditions.

One of the Abergavenny eisteddfodau (1845) – the eisteddfod procession passes in front of the Angel Hotel. (Image: © Illustrated London News Ltd. All rights reserved.)

One of the Abergavenny eisteddfodau (1845) – the eisteddfod procession passes in front of the Angel Hotel. (Image: © Illustrated London News Ltd. All rights reserved.)

Such a feeling amongst the Welsh people would, it was thought, act as a safeguard against protest and radicalism. As Lady Llanover put it, the Welsh language was a ‘firm and hitherto impenetrable barrier… to the progress of sedition and infidelity’.

Now, we might be tempted to see some wishful thinking going on here. This was, after all, a period of significant unrest in south Wales. The Scotch Cattle – a secret society that punished strike breakers and attacked company property – were active in Monmouthshire; the Merthyr Rising happened in 1831 just after Maria Jane’s brother had relinquished his post as county sheriff of Glamorgan; and the Chartist Rising culminated violently just down the road in Newport in 1839. If you were a figure of authority, a landowner, and particularly an employer of industrial workers, you had good reason to be nervous.

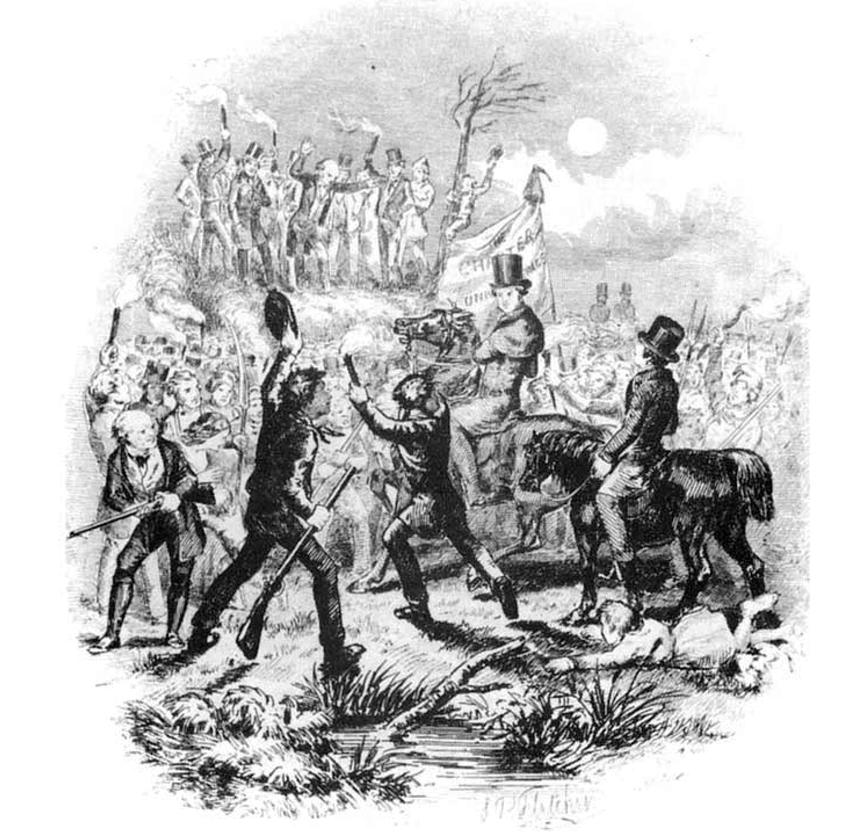

A contemporary, sensationalised image of a Chartist meeting, which emphasises a sense of drama and potential violence.

A contemporary, sensationalised image of a Chartist meeting, which emphasises a sense of drama and potential violence.

So no-one was more aware of the social and political context than the Llanovers, the Williamses and their ilk, and that fact casts their interest in Welsh traditional culture in an interesting and more complicated light than might appear superficially.

Their concern to preserve traditional songs in the language of the Welsh people was not just for innate musical and cultural value (though they undoubtedly did appreciate them from this point of view); it was also part of an effort to fight the contemporary tide of radicalism and protest by representing the Welsh in a reassuring light – as a literally and figuratively harmonious nation.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews