Musicians work with patterns. Repeating patterns of notes and repeating patterns of rhythms are what enable listeners to follow and understand a piece of music. Many composers have been fascinated by the effects that can be created by repeating the same pattern over and over again, something that music theory calls an ostinato. Some composers have taken such things to extremes: there is a Chopin piano mazurka where the final bars lead back to the beginning, and which has the instruction da capo senza fine (‘Repeat without ending’); a piece by Erik Satie called Vexations (which already repeats its bass line four times as an ostinato) instructs the performer to repeat the whole thing 840 times. The first actual performance of this piece (there have been very few), in New York in 1963, lasted 18 hours. Only one member of the audience was present for the entirety of that time, at the end of which he applauded and called, ‘Encore!’

Satie, Vexations

Satie, Vexations

Recording technology gives the musician the ability to control repeating patterns of sounds in ways that were not possible before. From the earliest days of recording sound on magnetic tape, composers were fascinated by the possibility of joining the ends of a piece of tape to make a loop which could be played over and over again by a tape recorder. ‘Looping’ was born.

Mechanical tape recorders like the one pictured below do not give the precise control of the sound that they seem to promise. In the 1960s, the composer Steve Reich became fascinated by what happened if you try to play identical tape loops on more than one machine. The loops will be fractionally different in length, and the machines will play at fractionally different speeds, and weird effects will result. Search for Reich’s pieces It’s Gonna Rain and Come Out if you want to hear what I mean.

A tape loop machine

A tape loop machine

Dogs and carrots

Today, however, a digital audio workstation running on an ordinary personal computer can manipulate sound with absolute precision. Musicians studying our Open University music degree are asked to experiment with the digital equivalent of Reich’s physical tape loops. Any sound whatsoever, once recorded, can be manipulated in this way to create new timbres and reveal hidden rhythms. Here, for instance, is the sound of a dog eating a carrot:

It is an easy task for a computer to make a ‘loop’ from a short part of this and repeat it over and over again – no need nowadays for cutting and splicing with a razor blade and adhesive tape:

And now, without the need for a second tape machine, we can play it against a very slightly shortened version of itself and hear the ‘phase effect’ in the sound that results:

Already by the end of half-a-dozen repetitions of the loop, the sound starts to gain a kind of internal rhythm. If the delay between one loop and another is increased slightly, the result is a pattern of shifting rhythms as the sounds go in and out of phase, which could be the starting point for a piece of music:

As we leave that particular dog to enjoy its carrot, we are left with the question: is this a musical idea requiring technology to enable it, or is it just a curious technological phenomenon? One lesson that can be drawn from it is that musicians, today as in all ages, will exploit whatever comes to hand to create new possibilities in sound.

The longest piece of music

The precision possible with digital technology, and the musical potential of looping sounds, lie behind the longest piece of music ever written. Longer than Satie’s Vexations, longer than any human performer could render Chopin’s ‘unending’ mazurka. Longer even than John Cage’s As Slow As Possible, which is still being played by a specially-built organ in Halberstadt, Germany (the last time a note changed in this piece was in 2013; the next will be in 2020).

The piece in question is currently being played in London, in what was formerly an inshore lighthouse on the bank of the Thames. It has the title Longplayer, and is created from a twenty-minute recording of Tibetan singing bowls. From this source recording, six fairly short pieces of music were derived. A two-minute segments of each is being played at any given moment, the exact starting times of each advancing slowly relative the others.

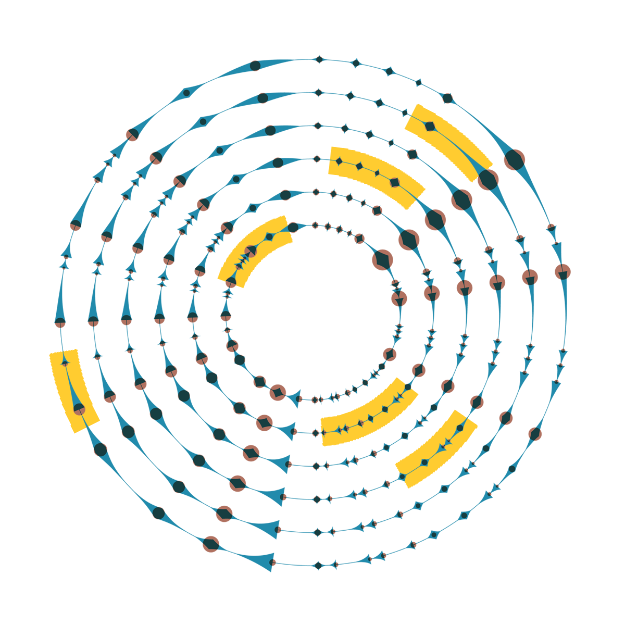

Diagram showing the progress of the pieces in Longplayer

Diagram showing the progress of the pieces in Longplayer

Longplayer has its own website where the process is described in detail:

https://longplayer.org/about/how-does-longplayer-work.

The piece began at midnight on 31 December 1999. It will play until midnight on 31 December 2999. Then, inevitably, it will begin all over again.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews