1.3 The origins of voice-leading analysis

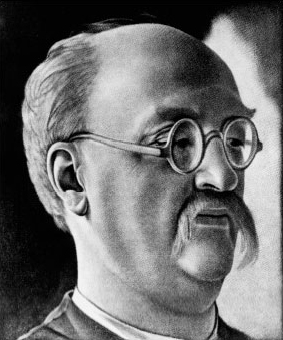

I want to begin by putting this method of analysing music into its historical context. Although the basic concepts of voice leading have a long history, the system of analysis you will be starting to use in this course is relatively recent, having been developed over the last hundred years or so. It is often associated with the name of the person who invented many of its terms and methods, the Viennese composer, pianist and music editor Heinrich Schenker (1865–1935) (Figure 1).

Schenker is best known today for his radical and controversial theories of tonal structure, but these (in particular, the concepts of foreground, middleground and background, which will be presented in this set of courses) were not developed until fairly late in his life, and were not published until after his death in 1935. Before this, his analytical ideas and observations began to develop through his work as an editor and critic.

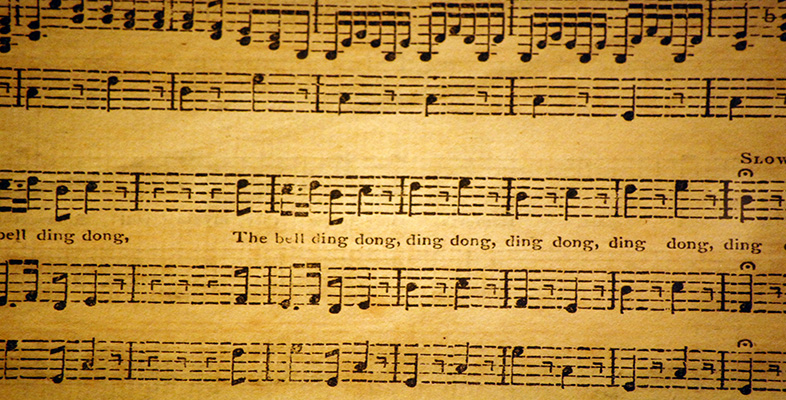

Schenker began to make analyses of music when he encountered difficulties in producing editions of musical works. A variety of sources may be used in preparing an edition, in particular the composer's original manuscript where that is available. Occasions arise where there are two or more possible versions of a passage, and in these cases Schenker thought that by analysing each of them, he could prove which was more logical and musical, and therefore identify the one the composer intended to use. Some of Schenker's editions are still in print today: for instance, the complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas (now published by Dover). In his work as a critic, Schenker was (rather unfashionably) opposed to any sort of Modernism, and believed in the supremacy of the tonal system, a stance which brought him into conflict with Schoenberg among others (the list of composers whose music he considered flawed included Wagner, Mahler and Debussy). He was also bitterly opposed to the traditional types of music analysis of the later nineteenth century; in particular, the idea of a stereotyped ‘recipe’ for models such as sonata form. Instead, he was concerned with the unveiling of hidden processes and linear shapes in tonal music (especially that of Bach, Scarlatti, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and Brahms).

Schenker's ideas have been extended, codified and debated, first by his friends and pupils, many of whom fled to America at the outbreak of the Second World War, and latterly by American, British and other scholars of music worldwide. Many articles in specialist journals such as Music Analysis in the UK and Music Theory Spectrum in the USA now assume an acquaintance with Schenker's ideas, methods and notations. His analytical method has been one of the most important topics in the theory of music since about 1970, and its applications within and beyond the field of tonal music are widely (and sometimes heatedly) discussed. As a result, the type of activity referred to as ‘voice-leading analysis’ in this course is often called ‘Schenkerian analysis’ by other writers (although the notations I will be using are not identical with those used by Schenker).