2.2 Listening for lines within the harmony

Now for an example taken from another first movement. This time the extract comes from the development section of a slightly earlier work, the Piano Sonata in C, K309. Here again, I want to demonstrate that simple chordal analysis can tell only part of the story. In this extract, voice-leading analysis can help us make sense of a rather difficult harmonic progression.

Activity 4

Listen carefully to the passage from the Piano Sonata in C, K309, several times, whilst following the score given in Example 4.

Click to listen to piano sonata

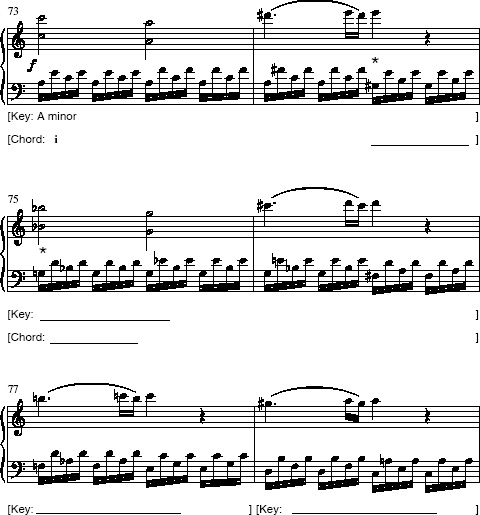

At first glance, the music seems to modulate wildly. Begin an analysis of these bars by annotating EXA001_004"Example 4 in the following ways. Use the pdf version of the score below to complete your annotation.

Click to open the score for annotating [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

-

Identify the main key areas through which the music passes. Enter the name of each key under the score in the brackets provided. The first key (A minor) has already been entered for you.

-

Enter roman numerals under the score in the places indicated (below the asterisks), to identify the chords Mozart employs at these two points, according to the key you have identified in each section.

-

Finally, consider the harmonic progression between bars 74 and 75. How does Mozart create a sense of logical continuity here?

Discussion

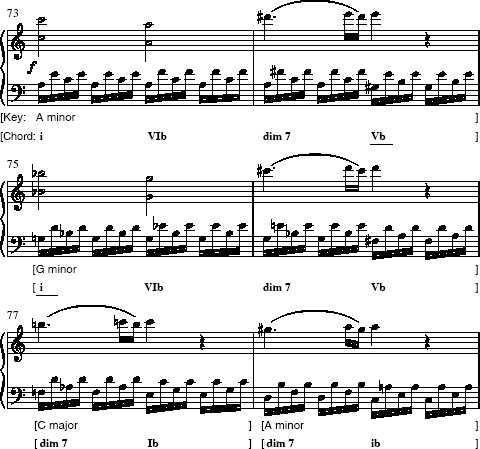

This exercise was intentionally difficult! Example 5 shows my suggestions of how a chord-function analysis might describe the whole of the extract. Clearly it begins and ends in A minor (chord i in bar 73, chord ib in the second half of bar 78), but it seems to pass through the unrelated region of G minor (starting in bar 75) only to return via C major (bar 77; see Example 5).

If we were to listen to bars 74 and 75 in isolation, the harmonic progression would seem illogical and almost disturbing. An E major chord (Vof A minor) in the second half of bar 74 is followed immediately by a G minor chord in bar 75. These two chords are, after all, harmonically very distant from one another on the ‘circle of fifths’, as are the two keys (A minor and G minor) that these chords imply. Such a juxtaposition of unrelated chords, we might think, would seem quite radical even in the harmonic language of Wagner or Debussy, let alone in a relatively early piano sonata of Mozart. (If you are able, you might like to play these two chords in isolation on a keyboard.)

In fact, a traditional harmonic approach would run into a few difficulties here. The analysis given in Example 5 does not really address the issue of the relationship between the areas of G minor and A minor. Yet, in the context of the whole passage, the progression seems entirely natural and convincing.

As we found with Example 1 above, the answer to how Mozart ‘gets away with’ the chord progression in these bars lies in large-scale lines. In the example from K333, we saw some linear voice-leading patterns in the melody. However, in this extract from K309, the solution to the problem lies in the bass line.

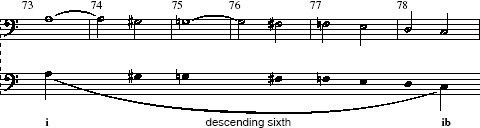

If we look at the bass from bar 73 onwards, we can see a beautifully logical descending line starting with A, and moving step-wise through some chromatic pitches to its goal, the lower C (Example 6).

In technical terms, we would say that the bass outlines a large descending sixth from A to C (from an A minor triad to its first inversion), filled out with passing notes (some of which are chromatic). It is these passing notes that generate the apparently deviant harmonies of the surface; without this large-scale linear process in the bass, the juxtaposition of the ‘unrelated’ chords would indeed sound anomalous and distinctly out of style. If you missed the sweeping bass line on the first hearing, play the track again, listening for how the bass gives shape to the extract.

In these examples, I have tried to emphasise the importance of listening closely to large-scale lines in the music, as opposed to the simple labelling of chords. You should not think of voice-leading analysis as a mathematical abstraction, but rather as an attempt to explain how we hear musical processes. Like any successful form of analysis, voice-leading analysis should always be based on your aural perception of a particular passage; the analysis should be an extension of your musical hearing. Moreover, a voice-leading analysis can actually shed light on certain aspects of Mozart's style (we saw, in my first example, how Mozart's smooth voice-leading was the hallmark of his style, while my hypothetical example was unstylistic).

We can conclude, then, that a simple labelling of vertical sonorities (chords) is not really enough for us to explain the logical processes that underlie Mozart's harmonic language. Even in a simple homophonic texture such as this, the style is rooted not just in harmony, but in counterpoint.

In the next section, you will explore the system of voice-leading analysis that attempts to codify and explain this contrapuntal aspect of Mozart's language.