2.1 Religion and national identity

As Colley suggests, minorities (or in Ireland’s case, the majority) who did not conform to Protestantism were not recognised as part of the British nation. Indeed, since the sixteenth century, various laws had restricted the ability of people who did not conform to the established churches of Britain and Ireland to participate in civil, military and political life. This was because if a person refused to conform to the religion of the state, their loyalty to that state was seen to be open to question. The terms ‘dissenter’ or ‘Nonconformist’ were often used to describe people (such as Roman Catholics and certain Protestant groups, including Baptists, Methodists and Quakers) who fitted into this category. While dissenting Protestants were permitted greater involvement in political affairs as the eighteenth century progressed, Roman Catholics remained subject to a range of penal laws for much of the century (Dickinson, 2007).

Although the idea of discriminating against a group of people on the basis of their religion was becoming increasingly difficult to justify, it was the need to recruit men into the British armed forces that proved to be the driving force behind Catholic relief efforts in the late eighteenth century. Legislation had long been in place to prevent Catholic military service, but in practice thousands of Catholics from Scotland and Ireland had served in British armed conflicts. By the 1770s, there emerged a growing body of opinion that removing the laws that prevented them from doing so legally would encourage further recruitment (Colley, 2003). It was for this specific purpose that the first Catholic relief acts were passed in the Irish Parliament in 1774 and the British Parliament in 1778.

However, not everyone in the United Kingdom was pleased with these developments. In 1780, a member of the British Parliament, Lord George Gordon (1751–1793), began to stir up public support for repeal of the British Catholic Relief Act of 1778. To achieve this aim, Gordon established a new society called the Protestant Association. This organisation quickly won a great deal of public support and, on 2 June 1780, Gordon led a crowd of 40,000–60,000 people to the House of Commons to submit a petition calling for the repeal of the Act (Jones, 2013, p. 80). Details of that event, and the rioting in London that ensued, were reported in numerous pamphlets, newspapers, monthly and annual periodicals.

Activity 3

Read the following extract from a newspaper report printed in the London Evening Post, one of the most popular newspapers at the time (with a circulation of about 4000–4500). The report outlines the outbreak of anti-Catholic rioting in London. Remember that newspaper reports are not impartial; this activity will help you to develop your abilities to recognise the bias and political sympathies of the author. Please note that contemporaries frequently referred to Roman Catholics as ‘Papists’ and their religion as ‘Popery’, both terms derived from the title of the head of the church.

As you read the extract, jot down some bullet points or notes in response to the following questions:

- What is the author’s attitude to Roman Catholicism?

- Who are the protesters described in the reading? What identities (religious, national or otherwise) are attributed to them here? Are these identities compatible?

Extract from London Evening Post, 1 June 1780

Yesterday morning, pursuant to a resolution of the Protestant Association, the Protestants of the city of London, Westminster, and Southward, met in St. George’s Fields, where Lord George Gordon joined them about eleven o’clock. Between eleven and twelve they set out (six–a–breast) over London Bridge, through Cornhill and the city, to the amount of about fifty thousand men, to the House of Commons with the Protestant Petition, against the bill passed last session in favour of the Roman Catholicks, which was carried on a man’s head, where Lord George Gordon presented it. They made a noble appearance, and marched in a very peaceable and quiet manner. It is supposed to be the largest petition ever presented to a British House of Parliament.

… they marched in four divisions to Old Palace–yard, in the following order. – London division first, which consisted of near 20,000 persons: these were succeeded by the Westminster division: after them came the division of the Borough of Southwark, and the fourth division, consisting of the Scotch, resident in London, preceded by a bagpipe playing, brought up the rear. The Archbishop of York passing along Parliament–street in his coach, at the time the procession was in motion, was much hooted by the populace, who seemed determined to stand up for their religious rights against the introduction of Popery, and resolved to defend themselves at all hazards from the pernicious effects of a religion subversive of all liberty, inimical to all purity of morals, begotten by fraud on superstition, and teeming with absurdity, persecution, and the most diabolical cruelty. It was a glorious and most affecting spectacle to see such numbers of our fellow citizens advancing in the cause of Protestantism…

…His Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester; Dukes of Devonsire, Richmond, Roxburgh, Earl of Shelburne, Lord Camden, the Bishop of Peterborough, and many other patriotic noblemen, had their carriages conducted with great respect and honour to the door of the House. Several of the Ministerial Lords were treated very roughly.

His Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester, when desired to continue to espouse the Protestant cause, nobly replied, "Gentlemen, while I have life I will espouse the cause of the Protestant religion and British liberty.'

…Lord George Germain was treated with great severity; he had porter thrown in his face, but as he came to the House, before the mob became outrageous, he escaped without further injury.

Specimen answer

- The author has a negative attitude towards Catholicism, claiming (for example) that ‘Popery’ threatens liberty and morals and was born out of superstition and ‘diabolical cruelty’.

- The protesters are identified at the outset by their religion. They are Protestants defending their ‘religious rights’. There are some references to national identity here, too, though. A division of the Protestant Association is described as the ‘Scotch, resident in London’ who were ‘preceded by a bagpipe playing’ as they marched. Later in the extract, a quote from Prince William Henry, the Duke of Gloucester (1743–1805), expresses his support for ‘the cause of the Protestant religion and British liberty’. Based on this article, we could conclude that the protesters are Protestant in religion; residents of London; English and Scottish, British; and anti-Catholic. All of these identities appear to be entirely compatible with one another.

Discussion

The language used in this newspaper report to describe Roman Catholics is very negative. While this kind of language may seem surprising to modern readers, it was not at all unusual to find such sentiments expressed in English-language publications from this period, from newspapers to the Book of Common Prayer. The notion that Roman Catholicism was ‘superstitious’ in nature stemmed from the idea that Catholics held beliefs and engaged in religious practices that had no basis in the Bible. Various wars with France, a country led by an absolute monarch, over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries meant that Catholicism was also particularly associated with ‘slavery’, ‘tyranny’ and ‘arbitrary power’.

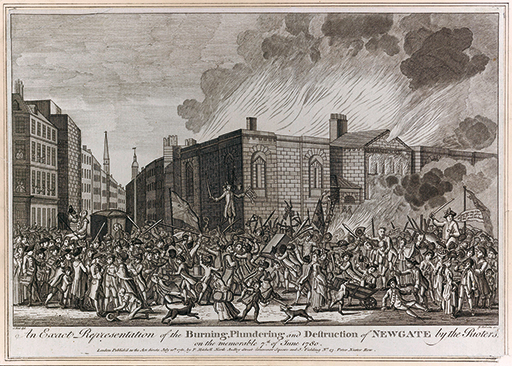

As you will have gathered, the orderly procession to the Houses of Parliament to present the ‘Protestant Petition’ descended into rioting, depicted in Figure 4 below. The riots continued for a week during which over 700 people are thought to have been killed. Although the violence was focused in London, anti-Catholic unrest was evident in other British cities, too. In fact, reaction to the relief legislation had been so strong in Scotland that the measure had not been imposed there. Although the first Catholic Relief Acts were promoted by the government for quite practical reasons, the Gordon Riots show us that by introducing Catholic relief measures at a time when Britain was at war with France, the government was seen to be undermining what it meant to be British for a great number of people.