3 Catholic emancipation

Despite at times intense opposition, more Catholic Relief Acts were passed by the Irish Parliament in 1778 and 1782, but the major breakthrough came in 1793 when Irish Catholics were granted freedom of worship and admission to most civil offices. Furthermore, Roman Catholic men in Ireland who met the same qualifications as their Protestant counterparts were permitted to vote in public elections (Dickson, 1999). Significant changes had been evident in Britain too and, in 1791, an extensive English Relief Act permitted Catholics to practise law and granted them the freedom to practise their religion without penalty. However, Catholics in Britain and Ireland could not yet sit in Parliament, and Catholics in Britain could not yet vote.

Calls for the provision of full civil rights for Catholics – or Catholic emancipation - gathered pace in the early nineteenth century but widespread public opposition remained evident across Britain. Societies such as the Protestant ‘Brunswick Clubs’ were established to organise opposition, mass meetings were held throughout England, Scotland and Wales, and hundreds of petitions were submitted to Parliament urging MPs to reject the ‘Catholic claims’. To some degree, this ‘no-Popery’ movement may have reflected British anxieties surrounding the recent influx of Irish immigrants into the country, the result of an economic slump in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. Reports of the popular movement in favour of parliamentary reform underway in Ireland also fed into escalating British opposition to the measure. However, Colley asserts that such factors do not fully explain the scale of the movement against Catholic emancipation in Britain. Instead, she points to evidence indicative of a strong sense of British identity among supporters of the movement and argues that these people ‘saw themselves, quite consciously, as being part of a native tradition of resistance to Catholicism which stretched back for centuries and which seemed, indeed, to be timeless’ (Colley, 2003, p. 330).

Activity 4

Look at the reading below. This is an extract from a Welsh newspaper of the period. Don’t be surprised if you encounter a few unfamiliar terms – this is common with historical primary sources – just refer to a dictionary to clarify any terms you don’t recognise.

Read the extract carefully and then answer the following question:

- What evidence do you find in this reading to support Colley’s view that there was a strong sense of British identity among ‘no-Popery’ campaigners?

Extract from North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality, 16th October 1828

Ancient Britons – The present circumstances of Ireland, are such as to demand the utmost wisdom and prudence on the part of our rules – the prompt and decided expression of protestant feeling – and the prayers of every lover of truth, that the black cloud which overhangs that fine country may not burst upon it. What has brought Ireland to its present state? Popery. Popery, not accompanied by rigorous penal laws, as formerly – popery, not ground down by persecution or pursued by relentless fury – but popery, conciliated, courted, caressed, encouraged by promises… Has the reformation ceased to be a blessing? Has popery ceased to be a curse?...

Ancient Britons – I have exercised the liberty of a subject under our protestant constitution, (of which I would say esto perpetua, let it ever exist) and set before you some important facts relative to Ireland and the popish question. Weigh them well. See what is your duty at this trying moment, and act accordingly. Let not Wales be silent when a nation’s voice should be lifted up by petition, in defence of Protestantism against popery. – Shew that you value the bible of the blessed God, by resisting the power that would rob you of its light – of its instruction – and of its consolations. Wickliff.

Specimen answer

In this extract the author addresses readers as ‘Ancient Britons’, and so seems to be speaking to fellow nationals. The author also makes references to the Protestant Reformation and discusses the threat posed by Roman Catholicism at some length, arguing that Catholics seek power and will not be satisfied ‘until a favourable opportunity present itself, of attempting the rescue of Great Britain out of the hands of [Protestant] heretics’. Colley suggests that anti-Catholic sentiment was a feature of ‘Britishness’, and there is evidence of that in this reading.

Discussion

At first glance, it certainly seems as though the author is invoking a sense of British national identity that ‘stretched back for centuries’. However, some Welsh people saw themselves as descendants of the original settlers of the British Isles, the ‘Ancient Britons’. So this article can also be seen as an appeal to the Welsh people specifically, rather than Britons in general.

Although there was a significant campaign against Catholic emancipation, the cause was not without its advocates in Britain. For instance, Parliament received many petitions in favour of the measure from all over the island, and certain printed publications also promoted it. It is also worth noting that appeals to British national sentiment were not the exclusive domain of those who harboured anti-Catholic sentiment. To give just one example, during debates on the issue in the House of Commons, Ralph Leycester (1764–1835), MP for Shaftesbury, argued that emancipation was ‘a measure of justice, of policy, of charity. It was not an English measure, nor a Scotch measure, nor an Irish measure – it was a British measure. It was not a Protestant measure, nor a Popish measure – it was a Christian measure’ (quoted in Ditchfield, 2003, p.76). You can see here that appeals to the idea of ‘Britain’ and ‘Britishness’ could be used by both sides to add a sense of legitimacy to their claims.

The campaign for Catholic emancipation proved successful in 1829, when a Catholic relief bill was passed granting Roman Catholic men the right to sit in Parliament, to vote and to enter all but the highest public offices. In contrast to the response to the Catholic Relief Act of 1778, which had led to violence in London, no major riots took place in 1829, no Catholic property appeared to have been destroyed, and no one was killed. Some historians suggest that this is evidence that Britons were becoming more tolerant, whereas others note that the measure had been government-led (and, in part, a response to events in Ireland that you’ll study in Section 5).

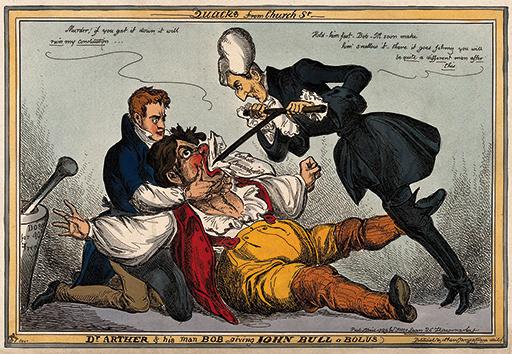

The idea that Catholic emancipation had been forced on the British population against their better judgement is reflected in Figure 5. It shows John Bull being held down by Robert Peel, the home secretary. The Duke of Wellington, the prime minister, shoves a piece of paper with the words ‘Catholic Emancipation’ written on it down John Bull’s throat. As this is happening, John Bull calls out, ‘Murder! If you get it down it will ruin my constitution’. Wellington assures John Bull that once he swallows the paper, he will be ‘quite a different man’.

This particular cartoon satirises the idea that Catholic emancipation was a breach of the ‘Protestant constitution’, a popular cry of those opposed to the measure, represented here by the John Bull character. Indeed, ‘no-Popery’ campaigners represented Catholic emancipation as unconstitutional on the basis that Catholicism, so closely associated in the public imagination with ‘slavery’, ‘tyranny’ and ‘arbitrary power’, was simply incompatible with British laws and liberties. Of course, the idea, suggested in the cartoon that John Bull would be a ‘different man’ once he had swallowed Catholic emancipation is thought-provoking. If Protestantism and Britishness had been synonymous up to this point, what was to become of ‘Britishness’ now that Catholics had been granted a measure of equality? The next section will consider the movement towards electoral reform, which can be seen as a further factor in the ongoing formation of British national identity.