Research into physical immortality is big business. Just try searching Google for the CEO of Apple Computers and biotech firm Genentech founded Calico (est. 2013). It's a company backed by a billion dollars of investment which aims to ‘devise interventions that slow aging and counteract age‑related diseases.’

The millionaire English gerontologist Aubrey de Grey, established the charity which focuses on the potential of cellular repair to extend lifespans indefinitely. De Grey has claimed provocatively that the first human to live to the age of 1,000 years has probably already been born. Meanwhile, Russian billionaire, Dmitry Itskov founded the ‘2045 Initiative’ in 2011, with the goal of achieving a cybornetically-assisted immortality by the year 2045.

However, the potential of immortality raises significant ethical concerns.

Suzanne Newcombe’s research (2017) has focused specifically on Indian techniques for longevity and immortality which have a very long history. One specific incident she has explored was the 1938 kuṭīpraveśika rejuvenation treatment of Pandit Mohan Malaviya (1861–1946), nationalist leader and chancellor of Benares Hindu University by a sadhu reputed to be over 200 years old at the time (Swami Tapasviji aka Tapsi Baba (c. 1770?–1955).

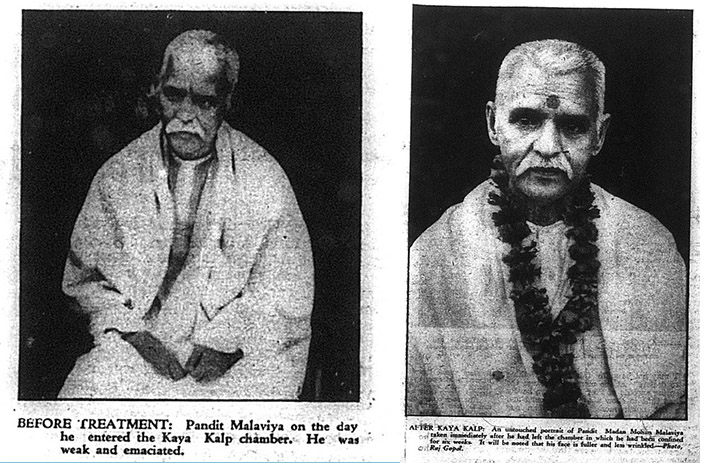

Photographs of Pandit Malaviya before and after his kutipravesika as appeared in The Illustrated Weekly of India and were syndicated worldwide (Lal 1938).

Photographs of Pandit Malaviya before and after his kutipravesika as appeared in The Illustrated Weekly of India and were syndicated worldwide (Lal 1938).

A contemporary photograph of the kuti later built by Tapsi Baba.

A contemporary photograph of the kuti later built by Tapsi Baba.

Listen to an audio recording below, in which Religious Studies scholar Suzanne Newcombe and philosopher Carolyn Price discuss some of the ethical implications of immortality.

Transcript

SUZANNE NEWCOMBE

Hello. I’m Suzanne Newcombe, a lecturer in religious studies.

CAROLYN PRICE

I’m Carolyn Price. I’m a senior lecturer in philosophy.

SUZANNE

Today, we’re going to talk about some of the ways that philosophy and religious studies approach immortality. One of the things I’ve been researching over the past few years are practices aimed at indefinite life extension in India. One practice in particular that has been revived in recent years has really, it caught my imagination and it’s called the kuṭīpraveśika treatment.

The kuṭīpraveśika treatment is expensive and time consuming. Ideally it takes place in a purpose-built hut made to the proportions of the person to undergo their treatment. It has three interlocking chambers to keep out the light, sounds and breeze, and it approximates a womb-like experience. Ideally, the patient stays in this hut for 40 days drinking nothing but milk from a black goat and a special rejuvenation formula. The ingredients contain Amla, an Indian gooseberry, amongst a number of other secret ingredients.

According to the arabetic texts, during this process the body will go through a process of degeneration and the parasites will come out. Eventually the skin will sloth off, the teeth will fall out and the muscles will completely atrophy. But this is the turning point. And then the body is supposed to regenerate to essentially how you were as a healthy 20-year-old with slick black hair, god like powers of perfect memory, the strength of an elephant and a lifespan of over 800 years. In 1938, the Indian Independence campaigner and educational reformer Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya undertook this kuṭīpraveśika treatment. His treatment was syndicated in major newspapers throughout the world. And while he didn’t expect such a radical transformation, his rejuvenation was well publicised and before and after pictures were circulated.

So, as a religious studies scholar, what are my questions to do with this research: why am I looking at it; what am I interested in? When we’re looking at both historical and contemporary evidence about religious traditions or any tradition we often find that people are doing something slightly different than what they might be saying they’re doing in scriptures. And I find exploring the stories that people tell, looking at what evidence there is and trying to understand what people believe and what they’re doing is fascinating. Carolyn, what do philosophers find interesting about the idea of immortality?

CAROLYN

Immortality has interested philosophers for all sorts of reasons. One question that interests philosophers is what it would even mean for a person to live forever or even over a very long period of time. In particular, would it be you, the particular person or self that you are that survives. So suppose we’re thinking about people surviving after death, perhaps through resurrection or reincarnation when they no longer have the same body. Does it make sense to think that a particular person or self could be recreated in a new body? Or would we really just end up with a new person, someone who has a similar personality perhaps, some similar memories but who’s really a different person?

In the life extension treatment you describe Suzanne we’re not supposing the person dies and leaves their mortal body behind. But even so, we imagine someone surviving for a very long time, over centuries. And so we might expect them to undergo all sorts of psychological changes along the way. They might forget their childhood, their personality traits and their interests and attachments might change. So would we really have the same person at the end as we had at the start? A second question concerns the desirability of immortality. Is immortality something we should want? It might be suggested that immortality would make our lives more meaningful. Because we’d never stop being able to engage in meaningful activities. And we’d never stop appreciating values of those activities. But another view is that living forever would make our lives less meaningful because life would lose any kind of structure. It would become like one of those long running soap operas on the TV that just goes on and on in repetitive circles without ever reaching any sort of conclusion.

So, as a philosopher, I think I’m interested in much more general questions than you are as a religious studies scholar. Not questions about a particular practice relating to immortality, but questions about the concept of immortality in general. And I also think I’m taking a more critical or an evaluative approach. I want to understand whether we should want immortality and whether the concept even makes sense.

SUZANNE

As a religious studies scholar, my most fundamental questions are usually about exploring libs contexts rather than starting with the abstract generalities. I want to know what’s going on here. It’s not necessarily about what people should or should not do, although the ethical awareness is also very important in this discipline. For example, considering the kuti treatment I describe, I’m interested in the ethical implications of what might be quite an invasive and intense practice. Well what are the actual effects? Are people being harmed by undertaking this treatment, and who is it suitable for? Does it have unexpected consequences? And this kind of information can be useful for making ethical decisions. So on an individual level, should I try this myself; on an institutional, organisational policy level, is this something that arabetic retreat centre should offer for example? Or even on a level of national policy, so to what extent does the Indian government’s description of its traditional medicine match up with what’s happening on the ground?

CAROLYN

So it sounds as if the questions that concern you are very practical ones; whereas my questions as a philosopher are about immortality in principle if you like. But even so the philosophical questions I mentioned earlier do have implications for some practical questions that arise in our everyday lives regardless of whether or not immortality is a real possibility. For example the question of what it means for someone to survive as the same person or the same self, arises in everyday situations too. And that’s because while we do hang on to the same bodies throughout our ordinary mortal lives, those bodies change.

So we might wonder for example whether it’s right to prosecute a very old person for something they did when they were young and which they now can’t remember or relate to in any way. Or whether people should have some special say about what should happen if they become cognitively impaired in some way. And of course questions about what makes our life meaningful also arise in our ordinary mortal lives; just in our ordinary decisions about what kind of life to lead.

Even if you think immortality isn’t a real possibility, it can still be useful to think about the possibility when we’re thinking about these more practical questions. And that’s because sometimes thinking about an extreme possibility can help us to get clearer about a question or a problem. Or recognise possible answers or complications that wouldn’t otherwise occur to us. In that way it can help us to think more carefully and more creatively about these questions.

SUZANNE

Absolutely, the clarity that your philosophical thinking brings can be really useful as we explore religious beliefs and practices as scholars, and as we make personal and cultural value judgements about the ethics of various beliefs and practices and what we do or do not find acceptable as a society. I find looking at what might be the extreme or very extremely different beliefs and practices from what I’m personally familiar with, fascinating because they invite a very different way of being and can reveal our own cultural assumptions about how things should or should not be which we might not have been aware of before. Researching and thinking about very different beliefs and practices to our own, can be inspiring. It can help us think about different ways of being and perhaps better ways of being in the world.

END OF RECORDING

References

Lal, K. (Mar. 20, 1938). “Shut in a Sealed Chamber for Six Weeks: Pandit Malaviya’s Kaya Kalp and How It Was Done.” The Illustrated Weekly of India, pp. 26–7.

Newcombe, S. (2017) “Yogis, Ayurveda, and Kayakalpa” History of Science in South Asia, 5(2), 85-120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18732/hssa.v5i2.2

Study a free related course

-

Introducing the philosophy of religion

Learn more to access more details of Introducing the philosophy of religionIn this free course, Introducing the philosophy of religion, Timothy Chappell, Professor of Philosophy, asks what the words 'God' and 'religion' mean, and what it means to ask philosophical questions about them.

-

Introducing philosophy

Learn more to access more details of Introducing philosophyEver wondered what it would be like to study philosophy? This free course, Introducing philosophy, will introduce you to the teaching methods employed and the types of activities and assignments you would be asked to undertake should you wish to study philosophy and the human situation.

-

Religious diversity: rethinking religion

Learn more to access more details of Religious diversity: rethinking religionReligion is not necessarily what you think it is! This free course, Religious diversity: rethinking religion, introduces you to a selection of the vast variety of religious beliefs and practices in Britain today. Having some familiarity with religion and belief is increasingly required to make sense of issues of local, national and international...

Read more articles on philosophy

-

Choose your own philosophy adventure

Take part now to access more details of Choose your own philosophy adventure'Castle, Forest, Island, Sea' is a choose-your-own-adventure interactive that explores key questions in philosophy. Where will your chosen path lead you?

Activity

Level: 1 Introductory

-

Life After Death

Watch now to access more details of Life After DeathSuzanne Newcombe discusses what happens to us after we die in this short video..

Video

Level: 1 Introductory

Rate and Review

Rate this audio

Review this audio

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Audio reviews