3 The elusiveness of consciousness

Consciousness is, in a sense, the most familiar thing in the world: our lives consist of a succession of conscious experiences. Yet consciousness can also seem elusive and mysterious, and this section contains some activities designed to highlight this. Here is a simple exercise to start us off.

Activity 3

Think about the different varieties of conscious experience you have and make a list of them. Include perceptual experiences (sight, hearing, etc.), bodily sensations (pain, for example) and any others you can think of. Then turn to Reading 1, which is an extract from the opening chapter of David Chalmers's book The Conscious Mind (Chalmers, 1996), and compare your list with his. Do you find Chalmers's descriptions accurate? Are there are any points on which you disagree with him?

Click on the 'View document' link below to read David J. Chalmers on 'A catalog of conscious experiences' [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

Discussion

Chalmers notes that his catalogue is not intended to be exhaustive and you may have included items he omits. His list does, however, cover the main varieties of conscious experience, and it seems to me both evocative and, for the most part, accurate. There are only two points on which I would disagree with Chalmers. First, I think he misdescribes the feel of conscious thoughts (paragraphs 13–14). Such thoughts, he says, often have a distinctive qualitative feel, reflecting their subject matter: thoughts about lions, for example, have a ‘whiff of leonine quality’ about them. This does not reflect my own experience. I agree that occurrent thoughts often have a phenomenal character, but for me it is primarily the feel of uttering the thought to myself in inner speech – a feeling similar to that of saying it aloud, but muted. My thoughts are also sometimes associated with visual images and emotional feelings, though these tend to be vague and ill-defined. Secondly, I am not sure that Chalmers is right to claim that there is a distinct feel associated with the sense of self – a ‘background hum’, as he puts it, which accompanies our other more fleeting experiences (paragraph 17). For my part, I am not aware of such a feeling but only of specific experiences like those mentioned elsewhere in Chalmers's catalogue.

I suggest you refer back to your list and to Chalmers's catalogue as you work through this course. In philosophical discussions of consciousness it is common to focus on very simple experiences – usually visual ones – but it is important to keep in mind the range and variety of conscious experience, since theories of consciousness are intended to apply to all of them.

Chalmers concentrates on describing the feel of the various experiences he lists, but there is often more to an experience than its feel. Most experiences also carry information, or misinformation, about our environment (misinformation in the case of perceptual illusions, such as when a stick looks bent in water). So, visual experiences tell us about the colours, shapes and movements of things around us; auditory experiences tell us about the location and motion of objects; tastes and smells tell us about the substances present in our food and in the air; bodily sensations, such as pain and thirst, tell us about the condition of our bodies; and so on. States that carry information are known as representational states and the information they carry is known as their representational content (the terms ‘intentional state’ and ‘intentional content’ are also frequently used, with the same meaning). For example, suppose I have a visual experience as of seeing a blue circle in front of me. The experience has the representational content that there is a blue circle ahead. If there is indeed a blue circle there, then this content is true – the experience represents the world accurately. If there is not a blue circle there (if I am hallucinating, say), then the content is false – the experience represents the world inaccurately.

Activity 4

Do all conscious experiences have representational content? Can you think of any that do not? Does a headache carry information (about the state of blood vessels in the head, perhaps)? Does a buzz of excitement or a rush of euphoria? Does an orgasm?

Discussion

This question is a controversial one. It is widely held that some bodily sensations and feelings lack representational content. Some philosophers, however, argue that representational content is the essence of consciousness and that all conscious experience possesses it. I am not going to discuss the issue further here; I want you just to bear the question in mind and see if your opinion changes as we go on.

I said that consciousness can seem elusive and mysterious and I want to use the rest of this section to illustrate some aspects of this.

Activity 5

Look again at Reading 1, especially paragraphs 1–7. Chalmers highlights two ways in which consciousness seems mysterious. What are they?

Discussion

One point Chalmers mentions several times is that the phenomenal character of many conscious experiences seems ineffable – we cannot find words to describe it adequately. Another point he mentions is that, in many cases, the connection between a stimulus and the resulting experience appears arbitrary – there seems to be no reason why the experience should have the phenomenal character it does, rather than a different one.

Let us consider these claims in more detail, beginning with ineffability. Chalmers's point is that it is often hard to describe an experience in a way that really conveys what it is like and that would be informative to someone who had never had it. This is not just because experiences can be very complex. Indeed, complex experiences may be easier to describe than simple ones, since we can break them down into more basic components. For example, a wine critic may describe the bouquet of a wine by saying that it contains scents of peach, anti-freeze and grass clippings. But these more basic sensory experiences seem indescribable. How could we describe the smell of grass clippings? It is distinctive and easily recognisable but seemingly impossible to characterise. (Of course, we can describe it indirectly as ‘the smell you get from grass clippings’, but how could we describe what it is like in itself?)

It is worth dwelling on this point a little. Take a simple visual experience – looking at a blue surface, say. How could I set about conveying the quality of this experience to someone who had never had it? I might try comparing it to other experiences – saying, for example, that it is more like the experience of seeing green than it is like that of seeing yellow. But such descriptions would be of use only to someone who had already had those other experiences. What description could I give to someone who was congenitally blind? The only option, it seems, would to be make comparisons with non-visual experiences, but it is hard to find informative ones. (A famous example, cited by John Locke, is that of a blind man who had the idea that scarlet resembled the sound of a trumpet [Locke, 1961, vol. 2, 30]. Although not bad as such comparisons go, this still falls a long way short of capturing what it is like to see something red.) The same goes for experiences involving other sense organs.

In this connection is it interesting to note that we do not have distinctive words for phenomenal properties themselves. Take the experience a normally sighted person has when looking at a ripe tomato. What term should we use for the phenomenal character of this experience? We might loosely call it ‘red’ – in everyday speech we do sometimes talk of having red sensations or red afterimages. (An afterimage is the sensation one gets after staring at a bright light and then looking away.) But the experience – the mental state – is not really red, at least not in the same sense the tomato is. The experience is not coloured red. (It is true that if experiences are states of the brain, as many philosophers believe, then the neural tissues involved will have colours. But there is no reason to think they will be red. Your brain doesn't change colour depending on what you are looking at!) To get round this difficulty some writers coin special terms for phenomenal properties. The philosopher Joseph Levine, for example, uses ‘reddishness’ for the property possessed by experiences of red (Levine, 2001). Thus Levine would say that red things cause reddish experiences.

The claim that conscious experience is ineffable is closely related to another claim often made about it – namely, that it is subjective. The phenomenal character of an experience, it is claimed, can only be appreciated from the inside, from the first-person point of view. We might study the brain processes involved in a certain type of experience in the most minute detail, but we would not learn what the experience was really like unless we were to have it for ourselves. To emphasise the point, the phenomenal aspect of experience is often referred to as its subjective character – in contrast to the objective, publicly observable features of the brain states involved (Nagel, 1974).

Turn now to Chalmers's second point – the arbitrariness of phenomenal character. The idea here is that, in many cases, the connection between what an experience is of and the way it feels seems arbitrary. ‘Why should that feel like this?’ we are tempted to ask, reflecting on a stimulus and the experience it causes. Of course, as Chalmers notes, this is not true of all experiences. It is surely not arbitrary that the experience of seeing a cube and that of seeing a sphere should feel the way they do, rather than the other way round. But in many cases the connections do seem arbitrary. Colours, sounds and smells offer good examples. Why should the light reflected from a ripe tomato produce a reddish sensation (to use Levine's terminology) rather than a greenish one? Why do the sound waves produced by a telephone cause us to hear a ringing sound, rather than, say, a squeaky one? Why do the chemicals in newly mown grass produce the particular smell they do, rather than another?

Of course, there is much we do not know about the brain processes involved in sense perception. But even if we knew everything about them it is still not clear that this sense of arbitrariness would be removed. We might still be at a loss to know why particular brain processes give rise to the particular experiences they do – why nerve firings in a certain region of the visual cortex (the area of the brain associated with vision) give rise to a reddish sensation, rather than a greenish one, or why the stimulation of certain cells in the olfactory bulb (the brain region associated with smell) causes a smell of grass clippings, rather than, say, one of linseed oil.

The apparent arbitrariness of phenomenal character suggests a strange possibility. If the links between stimuli and the experiences they cause really are arbitrary, then perhaps the same stimuli do not produce the same experiences in everyone. Perhaps when other people look at blue objects they have an experience of the sort I have when I look at yellow ones – so that for them looking at a cloudless summer sky is like looking at a vast sandy desert. How would I know?

Activity 6

Could I tell by questioning other people if the phenomenal character of their blue and yellow experiences is inverted in this way? Pause and think for a few minutes.

Discussion

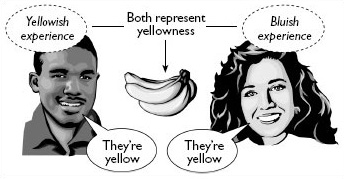

It seems unlikely that I could. Asking them if the sky looks blue or yellow won't help. They will say it looks blue – since they have learned to call things that produce experiences with this phenomenal character ‘blue’. The question is whether they associate the word ‘blue’ with the same phenomenal character I do. Nor will it help to ask them to describe the experience itself. For, as we have seen, it is very hard to describe simple experiences in a way that conveys their phenomenal character. Perhaps the best option would be to ask them to make comparisons between colours. If blue things produce yellowish experiences in them, then they will say that blue things look more similar to orange things than to green things, whereas if they produce bluish experiences, they will say it is the other way round. Even this would not be conclusive, however. For it might be that their other colour experiences are switched round too – so that, for example, the experiences they have when looking at orange things are like those I have when looking at green things and vice versa. If the whole range of their colour experiences was systematically inverted, then – arguably – all colour comparisons would be preserved and the inversion would be undetectable. This is referred to as the possibility of interpersonal spectrum inversion (Figure 3).

The possibility of spectrum inversion is sometimes said to show that the phenomenal character of an experience is independent of its representational content. The thought is that differences in phenomenal character need not make any difference to the way we classify objects and use colour words. You and I could agree on which things are yellow, even if these things produce different experiences in each of us. And the resulting experiences would represent the same thing – namely, the presence of something of the sort we both call ‘yellow’ – despite their difference in phenomenal character. We can imagine inversions in other sense organs, too. For example, patchouli might produce in you the smell sensation that almond oil produces in me. Again, however, both experiences could represent the same thing – the presence of patchouli. Considerations like these lead some people to say that the phenomenal character of an experience is an intrinsic, or non-relational, property of it – that is, one which it possesses in its own right, independently of its relations to other things. The representational properties of an experience, on the other hand, are not intrinsic, but determined by its relations to the object or property represented.

The conception of phenomenal properties just outlined – as ineffable, subjective and intrinsic – has been very influential in philosophical thinking about consciousness. Not everyone agrees that the conception is correct, however. Although consciousness can seem elusive when we reflect on it from the first-person point of view, many philosophers believe that our intuitions in this area should be treated with caution. Some writers deny that we are aware of intrinsic, non-representational features of our experiences, and many believe that conscious experiences are states of the brain that are, in principle, publicly observable and describable in physical terms.