The ancient Greek philosopher Plato (c. 427–347 bce) did not write long essays or treatises. Most of his philosophical works are written as dialogues, in which a small group of characters discuss a philosophical question. The dialogues are usually set in the recent past, and the other characters are often real people – prominent public figures, whom his readers might well have known. It is as if a modern-day philosopher gave up writing books and articles and began to write philosophical dramas, set in the 1980s perhaps, and featuring Margaret Thatcher, Stephen Hawking or David Bowie.

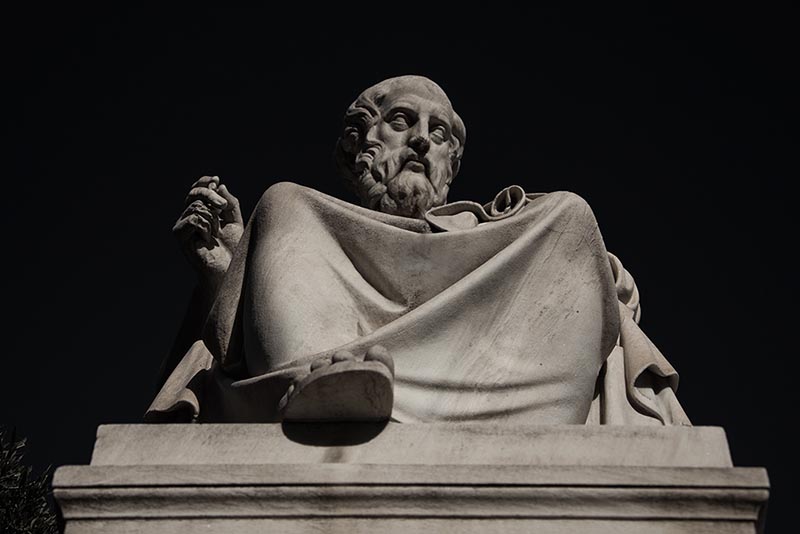

Marble statue of the ancient Greek Philosopher Plato. Academy of Athens,Greece.

Marble statue of the ancient Greek Philosopher Plato. Academy of Athens,Greece.

Plato’s earlier dialogues have some other distinctive features. The discussion is usually led by the philosopher Socrates. (The real-life Socrates was Plato’s teacher and mentor.) Socrates poses questions – apparently simple ones: ‘What is courage?’ ‘What is friendship?’ ‘What is piety?’. Usually, though, he avoids offering any answers of his own. Despite the simplicity of Socrates’ questions, the discussion tends to end in confusion: the characters cannot agree on an answer.

Why did Plato choose to write in this way? There are plenty of possible reasons. Most obviously, writing dialogues enabled him to present some complex issues in an engaging way. The characters are not just mouthpieces for philosophical ideas: they are portrayed as real individuals with a variety of foibles and flaws. They hog the conversation, interrupt each other, lose their tempers, tell stories and make jokes. This all helps to bring the discussion to life. It is likely too that Socrates’ preference for questions over answers reflects the methods Socrates used in real life.

There is, though, another possible explanation for Plato’s approach. It is not an alternative explanation, but one that is compatible with the reasons I just gave. It has to do with Plato’s own philosophical views – in particular, his views about the nature of knowledge. To explore this, we shall look at a passage from one of Plato’s dialogues, Meno.

The dialogue is named after one of the characters – Meno, a rather idle and vain young aristocrat from Thessaly in the north of Greece. The dialogue portrays Meno and Socrates exploring the nature of virtue. At one point, they start to discuss the difference between knowing something and merely having a true opinion about it.

Socrates has just pointed out to Meno that true opinion is just as good a guide as knowledge. Imagine two people: one knows how to get to Thessaly, while that other just has a true opinion about it. Both of them will be able to find their way there. Why, then, wonders Meno, do people think that knowledge is more valuable than true opinion?

This is one occasion on which Socrates breaks with his usual habits and offers an answer. Opinions, he says, are like the statues of Daedalus. Meno, understandably, asks what he means.

You may have heard of Daedalus – a mythical inventor associated with the island of Crete. Perhaps the best-known story about him concerns his son, Icarus, who drowned after flying too close to the sun. Here, though, Socrates is referring to another legend: Daedalus was said to have created statues that were so lifelike that they could move by themselves. A later writer, Palaephatus, tried to explain this legend by speculating that Daedalus was the first Greek sculptor to produce statues which stood with one foot in front of the other, instead of standing with both feet together (Palaephatus, 1996, section 21).

Statue of a young man, 6th c. BC

Statue of a young man, 6th c. BC

True opinions, Socrates suggests, are like the statues of Daedalus because they tend to wander off –in other words, they can easily change. Knowledge, in contrast, stays put.

To explain why, Socrates offers an account of what knowledge is. To know something, Socrates says, you must have experienced it or figured it out for yourself. To know how to get to Thessaly, for example, you need to have travelled the route yourself. To know a truth in mathematics or philosophy, you need to have figured it out for yourself – in particular, you need to understand not only that it is true, but also why it is true.

According to Socrates, this feature of knowledge explains why it is more stable than true opinion. The thought seems to be this: suppose that someone tells you that a particular philosophical argument is a good one, and you just take their word for it, without really understanding why. In this situation, you could easily be persuaded by someone else that the argument is a bad one. But once you understand why the argument is a good one – once you have thought it through for yourself – you cannot be persuaded otherwise. The knowledge has become your own, and it cannot be taken away by someone else.

This view of knowledge crops up in a number of dialogues, so it is likely that Plato endorsed it himself. But it has an important – and controversial – implication. It implies that we cannot come to know something just by taking someone else’s word for it, even if that person is an acknowledged expert. Nor can we simply soak up knowledge from books or online articles, no matter how well qualified the author. Relying on someone else will not give you knowledge. At best, it will supply you with a true opinion.

This is quite a radical departure from the way in which people often think about knowledge. Many people would regard the testimony of other people – friends, teachers, experts, eyewitnesses – as an important source of knowledge. According to Plato, however, this is not the case. To know something, you must have investigated it for yourself.

This is a striking suggestion, and it is certainly open to challenge. Here, however, I want to investigate how Plato’s view of knowledge might help to explain why he chooses to write dialogues, rather than essays, and why Plato’s Socrates is so reluctant to offer answers to the questions that he poses.

Plato’s view of knowledge could certainly help to explain Socrates’s reluctance to answer his own questions. By insisting that the other characters come up with their own answers, Socrates encourages them to think about the issues for themselves (Morris 2009). Hence, rather than merely sharing his opinions, he is helping them to achieve philosophical knowledge.

Plato's Academy, Roman mosaic from the House of T. Siminius in Pompeii.

Plato's Academy, Roman mosaic from the House of T. Siminius in Pompeii.

The same might be said of Plato himself. By writing dialogues, Plato, no less than Socrates, avoids simply presenting us with his opinions, but instead encourages us to think about the questions for ourselves. As we read one of his dialogues, we can imagine ourselves joining in the conversation, giving our own answers to Socrates’ questions and our own reactions to his arguments. The characters’ confusion at the end of the dialogue might well entice us to continue the investigation ourselves.

Whether or not we agree with Plato’s theory of knowledge, we can certainly appreciate the power of his writings to encourage us to think critically about our own views. This is an important habit, in philosophy and elsewhere.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews