African and African-Caribbean religions and the issue of stigmatisation

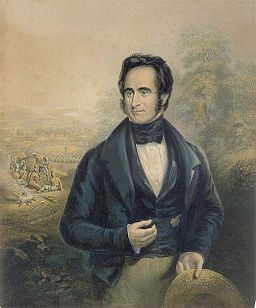

The Reverend Robert Moffat by George Baxter (1843)

Historically, African traditional religions, and consequently African-Caribbean religions, have often been demonised by the narrative constructed by Christian or Islamic religious authorities. The Christian negative meta narrative surrounding African and Afro-Caribbean religions started to develop with the arrival of the first missionaries in Africa, at the end of the fifteen century. Many of these missionaries, in trying to convert local people, in reality converted people’s local languages, beliefs, and practices into something associated with the ‘devil’.

The Reverend Robert Moffat by George Baxter (1843)

Historically, African traditional religions, and consequently African-Caribbean religions, have often been demonised by the narrative constructed by Christian or Islamic religious authorities. The Christian negative meta narrative surrounding African and Afro-Caribbean religions started to develop with the arrival of the first missionaries in Africa, at the end of the fifteen century. Many of these missionaries, in trying to convert local people, in reality converted people’s local languages, beliefs, and practices into something associated with the ‘devil’.

An example of this Western tendency is that of Reverend Robert Moffatt, an English missionary who went to Batswana in order to convert locals to Christianity.

When Moffatt arrived among the Ewe (one of Batswana local tribes) to start his work of conversion, he started to study the local culture and beliefs but with ‘Christian Western eyes’. This tribe’s religious system was called Badimo, which in local language means ‘ancestors. During his work of conversion, Moffatt transmuted the concept of Badimo by renaming it as ‘devils’ (Comaroff, J., and Comaroff, J., 1991). Furthermore, in his report ‘he represented the (di)ngaka [diviner-healer(s)] as agents of darkness or servants of Satan’ (Itumeleng D. Mothoagae, 2018).

The wrong and negative work of translation carried out by missionaries such as Moffatt, helped the West to create a negative stigma and image of African or African-Caribbean religions and cultures as a whole.

As Mojola states in his book Postcolonial translation theory and the Swahili Bible:

postcolonial approaches to translation … are primarily concerned with the links between translation and empire or translation and power as well as the role of translation in processes of cultural domination and subordination, colonisation and decolonisation, indoctrination and control and the … hybridisation and creolisation of cultures and languages. (2004:101)

The presentation I gave for Black History Month tried to decolonise the Western cultural stigmatisation that still surrounds African and African-Caribbean religions even today.

The Middle Passage

The forced and constant movement and encounter of different people, languages, goods, cultures, religions, and objects, in the Atlantic space, assisted the development of new religious identities...We cannot forget that the inception of African-Caribbean religions lay primarily in one of the most horrific and historical inhuman experiences: the transatlantic slave trade. The transatlantic trade started in 1526 by the Portuguese (supported economically by the Vatican), but was simultaneously joined by almost every European country. The slave trade lasted for 400 years during which time more than a million Africans lost their lives, and those who survived lost their African names and identities forever!

The presentation is a brief introduction to the inception and development of African-Caribbean religions and cultures. It focuses in particular on Cuban Santeria, on Vodou in Haiti and on Rastafari in Jamaica, which are the most popularly known African-Caribbean religions. Their inception was the result of a clash, with the mixing and blending of African and European religions, cultures and languages. The complexity, the struggle, and the wonderful creativity hidden behind the formation of African-Caribbean religious and cultures was often the outcome of a form of resistance or accommodation to the dramatic and violent context of the plantation society.

The forced and constant movement and encounter of different people, languages, goods, cultures, religions, and objects, in the Atlantic space, assisted the development of new religious identities that continue to be in motion today.

The Black Atlantic and the globalisation of African-Caribbean religions

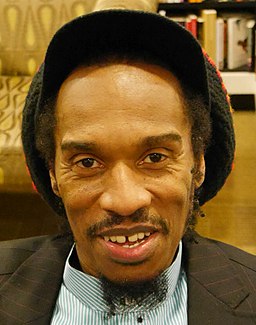

Benjamin Zephaniah, a poet and Rastafarian

The result of this multicultural encounter is what Gilroy called the Black Atlantic (1993).

Benjamin Zephaniah, a poet and Rastafarian

The result of this multicultural encounter is what Gilroy called the Black Atlantic (1993).

According to Gilroy, the Black Atlantic is a space that transcends nationality and ethnicity, and in which each cultural identity has to find new ways to deal with a new context and its syncretic interdependency. Gilroy saw the Atlantic as a space for cultural exchange and as a web or network of connections between Africa, the Caribbean, America, and Europe. Also, in his work Cultural Identities in Diaspora (1990), Hall sees the Atlantic world as a space where processes of creolisation, assimilation and syncretisation were and are still negotiated. He emphasised that Atlantic religions and identities are in a constant process of mixing and re-making. This was exemplified in the twentieth century by the advent of the Rastafari movement.

Today, Santeria, Vodou and Rastafari are not embraced only in the Caribbean, but they have travelled globally through social processes of globalisation such as migration and the development of new media and social networking. The globalisation of African-Caribbean religions and their attitude of being boundaryless (Niaah, 2008) led these religions to be localised, and to be embraced, developed, and re-created in more diverse contexts than the Caribbean, such as in Israel or Italy.

Therefore, despite centuries of Western negative narrative construction around African and African-Caribbean religions and cultures, through the following presentation and related blog I seek to decolonise such negative attributes and cast light on the cultural beauty and complexity behind the development of these religions. Their development represents the creative fire which was burning in the souls of the enslaves in order to resist and survive to a context of slavery. I wonder why these religions, nowadays embraced worldwide, are scarcely present or totally absent within the national curriculum framework? Why we don’t study them? Why is there scarce interest in African or Afro-Caribbean religions?

Rate and Review

Rate this video

Review this video

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Video reviews