1 Modernism

It is worth spending a moment now to untangle some of the terms that will be used explicitly in this course and that you will regularly encounter in readings on interwar society.

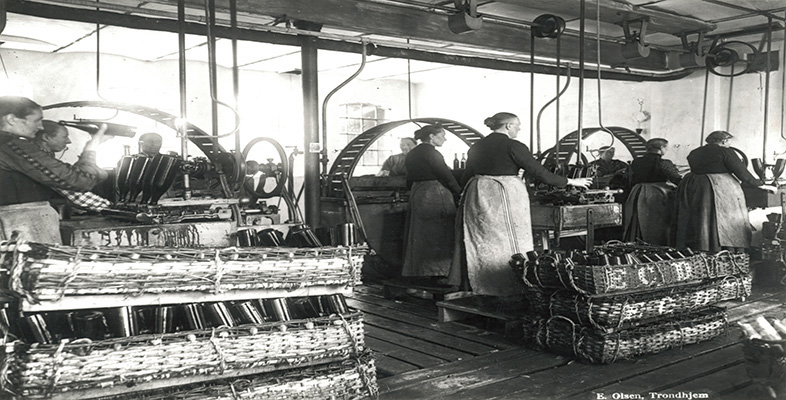

First, ‘modernisation’, which is a process of evolution, by which early modern and pre-industrial societies are transformed into modern societies through industrialisation, urbanisation, rationalisation, secularisation and the widening of the political community. Most historians suggest that modernisation began in Europe during the eighteenth century (Cocks, 2007, pp. 27–8), continued throughout the nineteenth and reached maturity in the twentieth.

Second, ‘modernity’, which is the experience of modernisation, an articulation of feeling modern or a sense that a break with the past has occurred, which is expressed in either positive or negative terms (or even both simultaneously). Historians have argued that there is no one moment of modernity in the 200-year period from c.1750 to c.1950; instead, there are multiple moments of modernity, which often occur in particular sites. However, a number of historians have highlighted the period 1880–1940 as a particularly important moment of modernity across Europe (Rieger and Daunton, 2001, pp. 1–4).

Third, ‘modernism’, an artistic movement that flourished in Europe from the late nineteenth century through to the interwar years. Many historians have argued that, as a narrative of change produced by an artistic elite or avant-garde, modernism had little to do with wider social change. However, modernism permeated European society more generally through the modernist architecture of new social housing projects, and the use of modern art and design by a range of political movements on the right and left (including the Republican government in Spain and the Fascists in Italy). If ordinary people were not conversant with modernism, many, especially in urban environments, were aware of it. We will not look at modernist art in any great depth in this course; however, we will touch upon it as part of the broader experience of modernity.

We will look at a number of specific features that suggest that the interwar period was a distinctive and important moment of modernity: shifts in demographics; the character of modern urban life; new forms of mass media; changing lifestyles of women; and the increasingly interventionist approaches to managing the health and welfare of modern populations. The way in which we have separated these features is artificial. For example, shifts in demographics and changes in the lives of women shaped health and welfare policies; the mass media was a vehicle through which to debate change, but also a tool to promote it; and the experience of all these features of modern life was arguably most intense within the urban environment. Two issues, derived from the historiography, will shape our assessment of these features:

- The role of the First World War in the experience of modernity – was war an agent of social change? Or did it represent an interruption to a set of inevitable developments?

- The tensions inherent in the experience of modernity – were these felt more keenly in some sites as opposed to others? How did pro- and anti-modern discourses relate to each other?