Known as the ‘Festival of Lights’, the celebration features a candlelit procession led by ‘Lucia’, who wears a white gown and a crown of candles. She is accompanied by handmaidens (tärnor), starboys (stjärngossar), gingerbread men (pepparkaksgubbar) and Santa’s elves (tomtenissar). Together, they sing traditional songs, including ‘Sankta

Lucia’, while

serving special baked goods like lussekatter (saffron buns) and pepparkakor (ginger

thins), along with glögg (mulled wine) or coffee.

Families also observe the day by having one of their daughters (traditionally the eldest) dress as Lucia and serve breakfast in bed to the rest of the family.

A typical Luciatåg (candlelit procession)

A typical Luciatåg (candlelit procession)

The origins of St Lucia’s Day

St Lucia’s Day is rooted in both ancient Norse and Christian traditions. Lussinatta (Lussi Night), an old pagan celebration, marked the winter solstice and was linked to a mythical figure, Lussi, believed to bring misfortune to those unprepared for winter. People would stay up through the night to avoid her wrath.

In contrast, St Lucia of Syracuse was a 4th-century martyr who brought food to Christians hiding in the Roman catacombs, using a candlelit wreath to light her way while keeping her hands free. Over time, these traditions merged, and St Lucia’s Day evolved to symbolise ‘hope and light during the darkest time of the year’.

St Lucia of Syracuse

St Lucia of Syracuse

The commercialisation of Lucia

The modern-day celebration began to take shape in the early 20th century, gaining widespread popularity in the 1920s after the newspaper Stockholms Dagblad sponsored a national Lucia competition. As the commercial food industry grew in tandem, Lucia’s image became a key marketing tool, particularly for coffee brands.

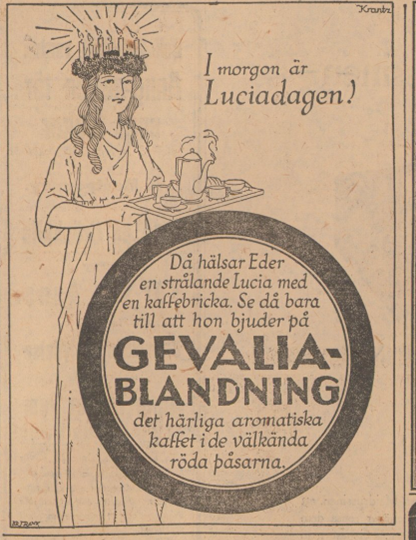

A 1923 advertisement for Gevalia depicted Lucia carrying a tray of coffee and buns, promoting the product as part of the Swedish Christmas tradition (‘a beaming Lucia greets you with a coffee tray’). The image of Lucia drew on classical mythology, embodying an idealised femininity influenced by the prevailing classical revivalist ideals of the time.

Advertisement for Gevalia coffee, Svenska Dagbladet, 12 December 1923

Advertisement for Gevalia coffee, Svenska Dagbladet, 12 December 1923

Coffee substitutes also seized the opportunity to leverage the ideological qualities of Lucia. In Brana’s more traditionally Swedish depiction of Lucia, customers are reminded that they ‘should be thankful that she treats you to a good, healthy drink instead of harmful bean coffee’. Here, Lucia’s white gown and golden hair evoke innocence and purity, reinforcing the purity of Brana coffee as a caffeine-free alternative. The crown of candles atop her head also symbolises enlightenment, particularly significant during a time when there was a growing movement against ‘poisonous’ coffee.

Advertisement for Brana malt coffee, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 December 1914

Advertisement for Brana malt coffee, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 December 1914

As St Lucia’s Day is also associated with cakes and biscuits, flour, yeast and baking powder brands also capitalised on Lucia’s image. An advertisement by Ekströms yeast flour features a rather abstract interpretation of Lucia bringing a breakfast tray to her husband. Employing a double entendre, the advertisement describes Lucia’s cakes – and, by extension, Lucia herself – as ‘a feast for the eyes, a pleasure for the palate’.

Similar themes are at work in an advertisement for Rumford baking powder, where Lucia is depicted with a plate of buns and coffee, alongside a recipe for lussekatter. The advertisement claims that she brings ‘a foretaste of the delights of Christmas baking’, both highlighting Lucia’s role in holiday traditions and appealing to the ideals of homemaking during the festive season.

Advertisements for Ekströms yeast flour and Rumford baking powder, Svenska Dagbladet, 9 December 1926 and 11 December 1933

Advertisements for Ekströms yeast flour and Rumford baking powder, Svenska Dagbladet, 9 December 1926 and 11 December 1933

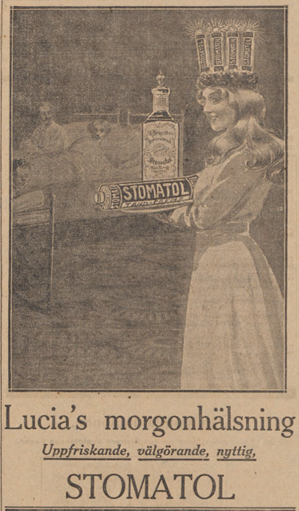

The use of Lucia’s image extended beyond the realm of food, appearing in advertisements for Anoka tights, the department store NK, the grocery store Konsum and even Stomatol toothpaste. The latter brand playfully parodies this national tradition in its advertisement by depicting St Lucia with a crown of Stomatol toothpaste tubes and a tray of toothpaste and mouthwash. The caption reads ‘Lucia’s morning greeting. Refreshing, beneficial, useful,’ cleverly extending these qualities to the toothpaste while connecting it to the spirit of the holiday.

Advertisement for Stomatol toothpaste, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 December 1911

Advertisement for Stomatol toothpaste, Svenska Dagbladet, 13 December 1911

Lucia in contemporary marketing

Lucia remains a prominent figure in Swedish holiday marketing, with portrayals now often subverting traditional gender and racial norms. Recent campaigns, such as this 2023 commercial for supermarket chain ICA, have featured men, young boys and Black girls in the role of Lucia.

These depictions promote a more inclusive understanding of the tradition, though they have sparked controversy. The selection of male Lucias in schools has also faced criticism, with some reports of them being excluded from celebrations.

In response, many Swedes have rallied on social media with hashtags like #JagÄrLucia (‘I am Lucia’) and #JagÄrHär (‘I am here’), reinforcing that the spirit of Lucia – symbolising warmth, generosity and hope – can be embraced by anyone, regardless of gender, race or background.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews