2 The 1950s

In 1954, in a court case called Brown v. The Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court officially ruled that segregated educational facilities were unconstitutional and ‘inherently unequal’ (quoted in Reynolds, 2010, p. 410). A Black lawyer, Thurgood Marshall, who worked for the NAACP, helped bring this case to the Supreme Court. But while it paved the way for an end to educational segregation, this court ruling alone did not immediately lead to change. President Dwight Eisenhower was reluctant to act, and the court did not actually set a timeframe in which schools would have to be desegregated.

The Supreme Court’s decision, however, did provide further impetus for Black people across the American South, encouraging many to resist racial discrimination. This resistance was not entirely new, but the language of rights and freedom espoused by the United States during the Cold War meant that it became more difficult for states to continue to refuse equality to Black citizens in key areas of education, transport, employment and housing. Continued violence by White people against African Americans – including the brutal murder of the fourteen-year-old schoolboy Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955 – also galvanised the civil rights movement.

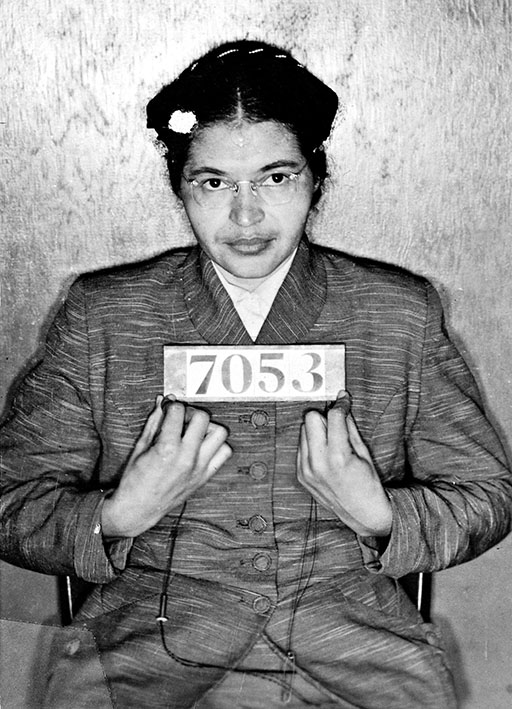

One of the most famous early examples of protest occurred in Montgomery, Alabama, on 1 December 1955. Across the South, Black people were usually required to move to the back of buses in order to allow White people to sit at the front. That day a Black woman, Rosa Parks, refused to move to the back, despite the protestations of the bus driver. She is now often remembered solely for this, but Parks was in fact a seasoned NAACP activist, who had been involved in over two decades of civil rights activism prior to this act of defiance (Theoharis, 2009, p. 116). Parks was arrested and taken to jail, but her actions encouraged Black leaders, including Jo Ann Robinson, who headed the Women’s Political Council, to organise a city-wide boycott of buses in Montgomery. These activists turned to a young Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., to help lead the boycott. A firm believer in non-violent protest, King proved himself to be a capable leader and an inspiring orator. The boycott was successful, forcing the Supreme Court to rule that Montgomery’s policy of bus segregation was unconstitutional. The city eventually agreed to integrate its buses by the end of 1956.

The following year, King and other Black Christian ministers across the South formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which would go on to play a major role in further civil rights activism. Despite its recent gains, however, the movement faced considerable resistance from White leaders in the South, and change was slow to happen. By 1957 fewer than 20 percent of schools had been integrated, and various forms of segregation remained a fact of life for many Black people (Greene, 2010, p. 7).