4 The birth of writing

Language first evolved in humans around one hundred thousand years ago (putting a precise date on its evolution is a difficult – and controversial – issue). Up until the end of the fourth millennium BC, however, its usefulness was limited to what was possible with the human voice. In essence this meant that language could only be used for direct communication between people who were physically in the same space. A speech, for example, could only be heard by those who were able to congregate within earshot of it. For information to be passed from generation to generation it had to be committed to memory and recited over and again down through the years.

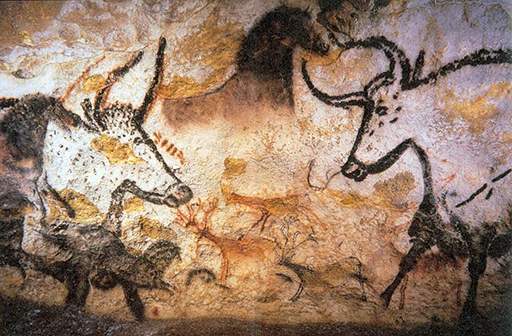

Around 5500 years ago, in the Sumerian region of Mesopotamia (in present-day Iraq), this began to change. Pictures and symbols had been used occasionally prior to this as a way of expressing ideas and messages – the earliest examples of human-made images date back some 40,000 years (Wilford, 2014). But they’d never been used as a systematic means of recording events and ideas. In need of a way to keep track of the goods they were trading, the Sumerians started engraving symbols on fired clay tablets. In Egypt at much the same time a similar scheme of symbols began being used as a way of recording the number and nature of people’s commodities. By the end of the fourth millennium BC, this innovation – writing – had developed into flexible and complex systems for recording the Sumerian and Egyptian languages.