3.7 It’s a trap!

The oil doesn’t stay in the source rock all that long. When the source rock is buried it’s not just temperatures that rise, but also the pressure, as hundreds and thousands of tonnes of other rock builds up on top.

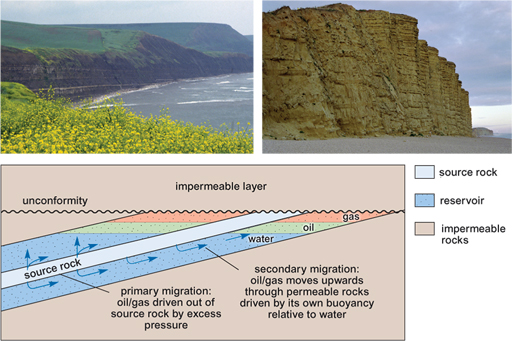

The pressure squeezes the liquid oil out of the source rock (this is called ‘primary migration’) and into any other permeable and porous rock that’s nearby. The porous and permeable rock which the oil is squeezed into is called the ‘reservoir’ rock. It has to be a rock which has lots of space in between the grains for the oil to be squeezed into, so sandstones are quite good reservoir rocks.

Because it’s less dense than the rock and any water that may be in the reservoir rock as well, the oil floats to the top (‘secondary migration’). If there’s nothing to stop it, then the oil will continue to migrate upwards until it reaches the surface. This is what’s happening at the La Brea Tar Pits and several oil seeps on the south coast of Dorset in the UK.

However, some rocks aren’t permeable and don’t allow the oil to pass through, trapping the oil in whatever rock it’s made it to. This impermeable rock is called the ‘cap rock’ as it’s found at the top of an oil reservoir. The impermeable cap rock can be another sedimentary rock like a mudstone, which has very fine grains that are very close together, or a salt. Because salt is also much less dense than other rocks, sometimes it too tries to float up to the surface, making some quite interesting structures.

The combination of a source rock, reservoir rock and cap rock are, together, called a ‘trap’. All three are needed, as well as just the right temperature and pressure history, to transform dead things into oil.

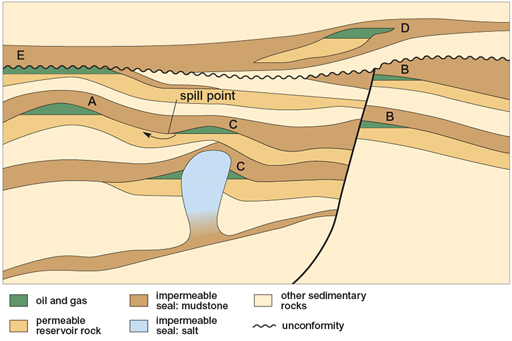

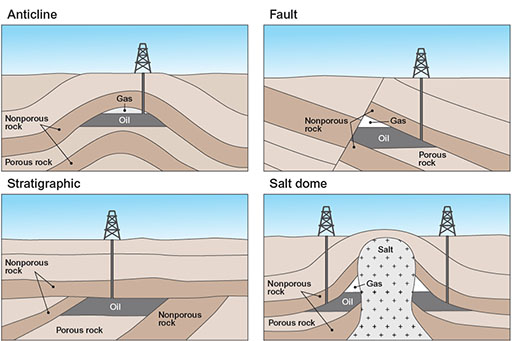

Types of traps

Sedimentary rocks form lots of different types of trap. Looking at Figure 3.11 below: A is an anticline trap caused by the folding; B is a fault that juxtaposes a reservoir against a seal; C are traps caused by a salt dome (either directly or because of folding derived from the buoyant migration of salt); D is called a ‘subtle trap’ caused by lateral variation in sedimentary systems, and E is a ‘combination trap’ where the combination of uplift, erosion and folding has abutted reservoir and seal rocks.