4.5 Impact of dredging

Many countries are beginning to understand the impact of dredging on the marine environment.

In the UK, for example, the British Marine Aggregate Producers Association has drawn up a biodiversity framework that its members must work to, while other governments around the world are implementing biodiversity action plans. Areas that are dredged can be monitored by ensuring that vessels dredging with production licences have an electronic monitoring system. This ensures extraction is limited to the areas defined in the licence and avoids fishing areas or areas with vulnerable habitats. If dredging is taking place close to the shore, detailed studies can be carried out analysing waves and currents to ensure sediment routes to beaches and coastlines are not disrupted.

Studies have been carried out on the re-colonisation of dredged sea bed, and the length of time they take to recover varies depending on the intensity of dredging. Studies have shown that it takes from one month to about five years for a sea bed to show complete recovery (Desprez, 2000). If areas of undisturbed seabed are maintained between dredge sites, there is a higher possibility of rapid re-colonisation. However, if the dredging has altered the material on the sea floor, for example, changing it from gravel to sand, it may not be possible for the organisms living on adjacent sea floor to migrate, as they require different material to live on. If that is the case, it may take longer for re-colonisation to occur, as organisms – or, more likely, their planktonic larvae – must migrate from further afield.

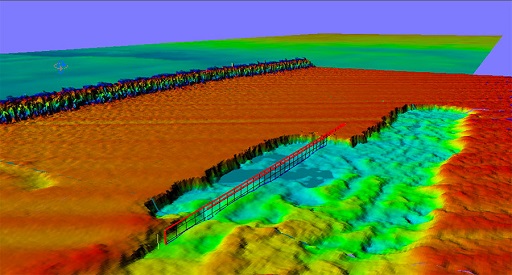

Even though re-colonisation may occur, the marks left from dredging often remain. The topography is permanently altered and the material on the sea floor is often changed. The most obvious change is increased water depth as material is removed. The infilling of pits, once dredging has stopped, is difficult as it depends on the ability of water currents to transport material to infill the holes. Only in areas dominated by mobile sand does the sea floor recover quickly. It is very rare that a current is strong enough to move gravel-sized pieces, so dredging holes and furrows are often infilled by fine sediment. Furrows only 30 cm deep when formed are still present several years later (Desprez, 2000).

So, you can see that as long as aggregate extraction is controlled by enforced regulation and given time, the marine ecosystem can recover from dredging. The physical effects of dredging determine the organisms that re-colonise the sea floor, as it can change the material that it is made of and these physical effects can be long-lasting.