4 The TOR network

The internet is a rich source of information for intelligence services around the world. Since the revelations by former US government contractor and CIA employee Edward Snowden, we know that the intelligence services of western countries such as the USA and UK collect and monitor data that is exchanged via the internet. However, the internet is incredibly versatile and, with clever algorithms and encryption techniques, networks can be created that allow for communications that evade monitoring, up to a point. The Tor network is a good example of this.

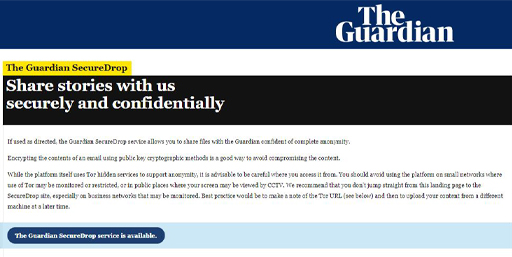

Criminals and terrorists use such networks but also, for example, news organisations that want to protect their sources (Figure 10).

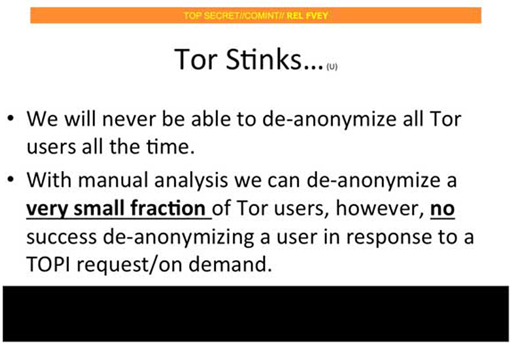

Security services, such as the US National Security Agency (NSA), have debated and complained about Tor in internal briefings (Figure 11).

Even a simple slide, such as the one in Figure 11, can convey an argument. In the next activity, you will dissect this argument. For the purpose of the activity, don’t worry about what ‘de-anonymizing a user in response to a TOPI request/on demand’ means. All you need to take away from that part of the slide is that there are certain communications on Tor that, so far, cannot be successfully de-anonymised. In other words, there are communications on TOR that hide the users’ identities and no way has yet been found to work out those hidden identities.

Activity _unit8.4.1 Activity 4 Mapping ‘Tor stinks’

Start by identifying the main claim that is put forward on this slide (following the first step of the recipe in Section 1).

Discussion

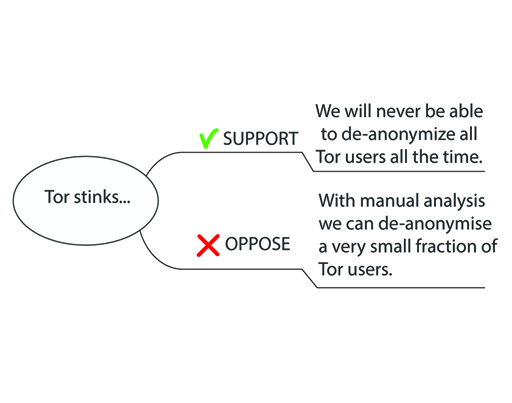

In this case, the main claim is made by the slide’s title: ‘Tor stinks …’ (Figure 12). In other words, the title puts forward the claim that Tor is a problem for the NSA or intelligence community.

Next, apply the second step of the recipe. In this case, there are no connecting words or phrases to help you. In such a situation, you can test whether a statement, say B, is supporting claim A by reformulating it as a short dialogue of the form:

| Speaker 1: | A |

| Speaker 2: | Why A? |

| Speaker 1: | B |

A similar strategy also allows you to test whether B opposes A. In that case, a dialogue of the following form should work:

| Speaker 1: | Not A |

| Speaker 2: | Why not A? |

| Speaker 1: | B |

The first bullet item on the slide ‘We will never be able to de-anonymize all Tor users all the time’ passes the dialogue test for a support relationship.

| Intelligence officer 1: | Tor stinks! |

| Intelligence officer 2: | Why does Tor stink? |

| Intelligence officer 1: | We will never be able to de-anonymize all Tor users all the time. |

Next, consider the second bullet:

With manual analysis we can de-anonymize a very small fraction of Tor users, however, no success de-anonymizing a user in response to a TOPI request/on demand.

The first part of this statement fits the dialogue test for an oppose relationship:

| Intelligence officer 1: | Tor doesn’t stink! |

| Intelligence officer 2: | Why not? |

| Intelligence officer 1: | With manual analysis we can de-anonymise a very small fraction of Tor users. |

‘With manual analysis we can de-anonymize a very small faction of Tor users’ says that there is a way to track at least some Tor users – even if it is only a small fraction. This suggests that Tor may not be entirely bad (from the perspective of the intelligence community). What you have here is an opposing claim, even if it is a very weak one.

You can add the supporting and opposing claims you found to your argument map (Figure 13).

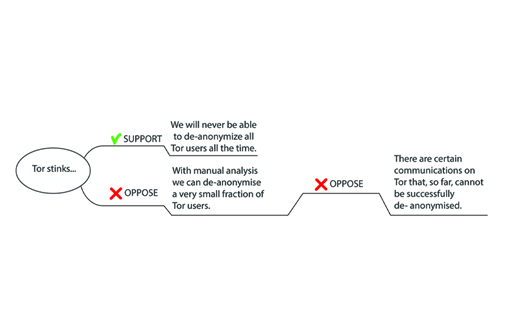

Finally, apply the recipe’s repeat step and add the second half of the second bullet on the slide:

however, no success de-anonymizing a user in response to a TOPI request/on demand.

Use the following reformulation (and don’t worry about the meaning of TOPI request/on demand):

However, there are certain communications on Tor that, so far, cannot be successfully de-anonymised.

You can work out that the author is directing attention to the idea that, in certain circumstances, there is no way to de-anonymise users, not even a small fraction of them. What you have here is an opposing claim that opposes the previous opposing claim! A visualisation with an argument map brings the idea across vividly (Figure 13).

Note that in the argument map the word ‘however’ is omitted from the second opposing claim. This connecting word is not part of the claim itself. As you already explored earlier, such words give us clues about the role of the claim that they are attached to. In particular, ‘however’ signals that what follows is in some way at odds with what came before it.

That concludes the argument-mapping activities for this session. We hope you took our advice at the beginning and didn’t worry too much if your maps differed slightly from ours. The key points are:

- You can defend the reasoning behind your maps

- You can follow the reasoning behind our maps as well.

To illustrate this, consider the final map of Activity 4 (Figure 14). We decided that the two bullet items on the slide present claims that connect to the main claim. However, the second bullet item can also be thought of as opposing the first bullet item. In that case, we get a map with a different structure (Figure 15). Note that this map isn’t necessarily better or worse.