1.3 Doubts still

The schemes of Llull and Leibniz were not universally applauded. Gulliver’s Travels, a satirical travelogue by Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), makes fun of the whole idea. Swift, who was 21 years Leibniz’s junior, describes Gulliver’s visit to the ‘Grand Academy of Lagado’. One of its resident professors is involved in ‘a project for improving speculative knowledge by practical and mechanical operations’. Swift’s Gulliver is openly disdainful:

Everyone knew how laborious the usual method is of attaining to arts and sciences; whereas by [the professor’s] contrivance the most ignorant person at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, may write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, law, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.

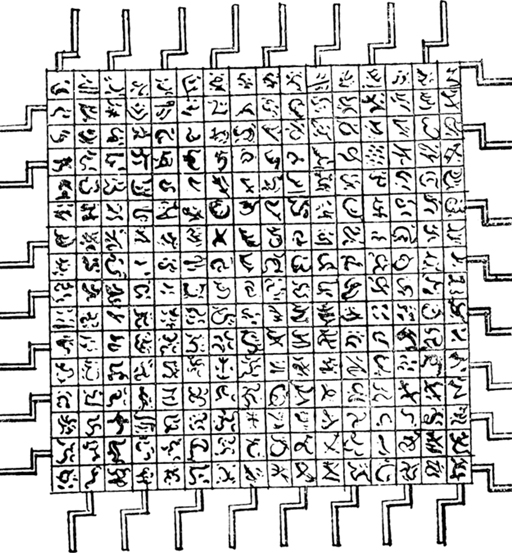

Gulliver goes on to describe how the machine – powered by the professor’s pupils turning iron handles – rearranges words resulting in several large books ‘of broken sentences, which [the professor] intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences’. Gulliver’s Travels includes an illustration of the machine (see Figure 5), with the iron handles clearly identifiable. Swift’s Gulliver concludes his description of meeting the professor in words that are unmistakably disdainful:

I made my humblest acknowledgement to this illustrious person for his great communicativeness, and promised, if ever I had the good fortune to return to my native country, that I would do him justice, as the sole inventor of this wonderful machine … I told him, although it were the custom of our learned in Europe to steal inventions from each other, who had thereby at least this advantage, that it became controversy which was the right owner, yet I would take such caution, that he should have the honour entire without a rival.

This swipe at the professor might also be an allusion to a quarrel between Leibniz and Newton. Both Newton and Leibniz claimed to have invented calculus, a mathematical tool that plays a pivotal role in Newtonian physics.

The next section looks at how, from the 19th century the idea to mechanise thought was taken to the next level. It also looks at how this programme to mechanise thought had run into theoretical difficulties by the middle of the 20th century. And further practical obstacles led to a major change of approach – away from the foundations laid by Llull, Descartes and Leibniz – by the end of the 20th century.