The French government

Perhaps private citizens are relieved of responsibility if we agree with the points on the previous page. And yet much of the cost of restoring Notre-Dame (perhaps most of it, depending on how expensive it becomes) will be borne by the French government, and other states may be unable to use the arguments just presented. For instance, states do not obviously have a right to spend their funds however they see fit. Since those funds are collected from the people through taxes and other means, it seems reasonable to expect that they should be spent only in ways that effectively benefit those people. Also, it is not overly demanding to expect a state to strive to do what is morally best for its people.

The ‘relationships’ point raised earlier may apply to states to some degree, if we believe that they are entitled to have greater concern for the wellbeing of their own citizens than those of other nations. Given this, a state may be morally permitted to spend its funds meeting the needs of its own people, even when there are needier people elsewhere.

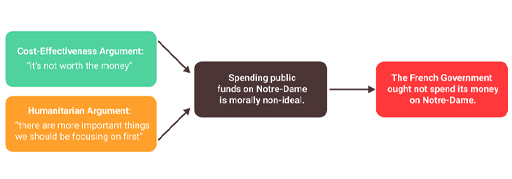

However, even accepting this, the French state is still faced with an ethical dilemma. France, like any other nation, has humanitarian problems within its own borders, such as poverty, disease and homelessness. Therefore, it is still vulnerable to the cost-effectiveness and humanitarian arguments (Figure 13).

Assuming that the full cost of Notre-Dame’s restoration reaches billions of euros, and will only accomplish a moderate gain in value, shouldn’t the French government spend tax funds in a more cost-effective way? Since there are people in France who lack access to housing, education or medical treatment, does the French government have a moral duty to help them before repairing historical buildings?